I lived in Manhattan for six years and remained only vaguely aware that the East River is not a river. It is a tidal race, the southern arm of the Sound which defines Long Island. And I was completely oblivious that where I drank my Sunday morning coffee, in Carl Schurz Park (at 86th street & East End Avenue), overlooks the birthplace of the United States Army Corp of Engineers as a civilian works organization. Without their skill and brains (and the largest man made planned explosion of the 19th century) New York would have remained a second class harbor.

And a thousand men, women and children might have been spared a terrifying and painful death.

A few minutes after 9:30 a.m. on Wednesday 15 June, 1904 “The General Slocum”, a 235 foot long, 37 foot wide side paddle wheel steamship built for passenger excursions, left the dock at East Third Street carrying 1,300 German Lutheran emigrants (mostly women and children) to a picnic on Long Island.

The Slocum’s three decks were barely half full, and the children waved to the people on shore as 68 year old Captain William Van Schaick guided her from atop the pilot house up the East River at 16 knots toward the Hells Gate.

Every high tide that pours into the Bay of New York swirls around the base of Manhattan and produces a titanic struggle in a rock garden between Astoria Queens, on the Long Island shore, and Wards Island in midstream.

Eighteenth century New York City resident Washington Irving described the Hells Gate this way; “…as the tide rises it begins to fret; at half tide it roars with might and main, like a bull bellowing for more drink; but when the tide is full, it relapses into quiet, and for a time sleeps as soundly as an alderman after dinner. In fact, it may be compared to a quarrelsome toper, who is a peaceable fellow enough when he has no liquor at all, or when he has a skinful…plays the very devil.”

And, because of the delay in the tide coming down Long Island Sound, there are four high and low tides per day, keeping the Hells Gate in perpetual motion. That made the glacier scared bottom of the East River a deadly obstacle course.

“Three channels existed…the main ship channel to the north-west of the Heel Tap and Mill Rocks; the middle channel between Mill Rocks and Middle Reef; and the east channel between the Middle Reef and Astoria, from which Halletstts Reef projected; and vessels having traversed one…had to avoid Hogs Back and several smaller reefs…(and avoid) Heel Tap Rock…Rylanders Reef, Gridiron Rock of the Middle Reef .” (p.264. Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers, Leveson Francis Yernok-Hartcourt 1888).

By the late 1840’s a thousand ships a year were running aground on rocks and shoals in the Gate, ten percent of every ship which entered.

In 1850 Monsieur Benjamin Maillefert was paid $15,000 to remove Pot Rock - “rising like a rhinoceros horn from a depth of thirty feet to within eight feet of the surface...right next to a shipping lane” near the Queens shore.

Maillefert lowered a canister of black powder on a rope and the resulting explosion managed to chip four feet off the top of the horn.

Two hundred and eighty-three explosions later and Pot Rock was safely 18 feet below the surface. Similar attacks on the Frying Pan and Ways Reef dismantled the great whirlpool which had spun south of Mills Rock for five thousand years. But the start of the American Civil War in April of 1861 gave the merchants of New York more pressing and profitable places to invest their money. Hells Gate remained closed to all but the bravest and most foolish captains.

Just before ten o’clock a boy on 15 June, 1904, a boy told deck hand John Coakley there was smoke in a forward stairwell. Coakley, who had worked on the General Slocum for all of 17 days, found the source of the smoke to be a storage room. He then made two crucial mistakes.

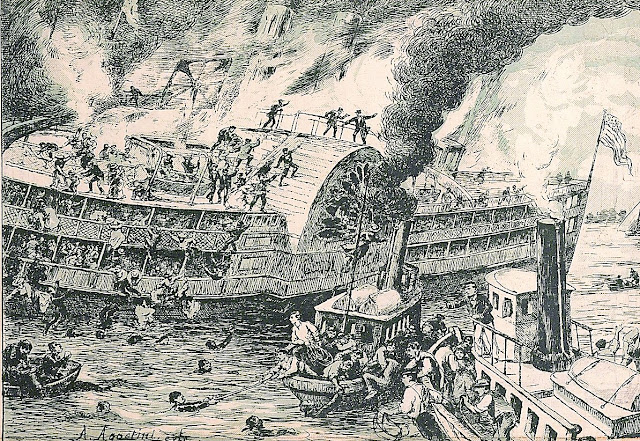

He opened the door, which fed fresh air to the smoldering fire. And when he ran for help, he left the door wide open behind him. Freed at last, the fire burst out. Crewmembers rushed to pull down a fire hose, but none of the hoses on board had been inspected since the Slocum had been built, twelve years before. At the first surge of water pressure the hose split apart. The crewmen then ran for another, but they had to search, since they had never had a fire drill. Meanwhile the fire was drawn through the open door and sucked up the chimney of the three-Decker stairwell.

Captain Van Schaick (above) was informed of the fire seven minutes after crewman Coakley had discovered it. Van Schaick had never lost a passenger and he decided now to steam into the Gate, heading, he said later, for North Brother Island, three miles ahead. There was a hospital there and a gentle shoreline where the passengers could safely wade ashore.

However, as he rang up for more power from the engine room, Van Schaick could not see he was fanning the hungry flames behind him, trapping the terrified passengers at the stern.

When they reached for life jackets, visible in overhead racks, passengers found them tied down with wires to prevent theft. Those who managed to break the wires and free the preservers found they crumbled in their hands. “

The hard blocks of cork inside were reduced to fine dust and had the buoyancy of dirt. Most people jumped over board without them. But some actually put them on, dropped over the side and plunged straight to the bottom.” Some of those who managed to stay afloat were mauled by the paddle wheels, still driving the General Slocum at full steam through the Hells Gate at 20 knots.

In 1871 General John Newton of the United States Army Corps of Engineers took over the work of finally rendering Hells Gate a safe passage. His first target was Hallet’s Point Reef, “, a three-hundred-foot rocky promontory that reached out from Astoria…” And this time General Newton intended to perform the entire task by a process he described as “subaqueous tunneling”.

A cofferdam was constructed extending the Astoria shore outward. And tunneling with pick ax and shovel from this extension, the reef was under-mined with four miles of galleries.

It took seven years altogether. Then, on 24 September, 1876, 30,000 lbs of nitroglycerine – the most powerful explosive available at the time – were set off by electric shock.

The explosion threw up a 123 foot plume of water. And the reef was gone. Hell's Gate got a little safer.

Meanwhile back in 1904, a witness at 138th street told the “Brooklyn Eagle” the General Slocum appeared in a cloud of smoke and fire, its whistles screaming, trailed by tugs, launches and even rowboats, all trying to help. But the General Slocum was too fast for them.

“The stern seemed black with people…some were climbing over the railings…the shrieks of the dying and panic stricken reached us in an awful chorus…One by one, it seemed to me, they dropped into the water. As the Slocum preceded, a blazing mass, I lost sight of her around the bend, at the head of North Brother Island”.

In 1877, General Newton built a sea wall around Flood Rock and another 70 foot deep shaft was dug, followed by the now standard shafts and galleries reaching out below the East River bed. At the same time a similar process was underway at Mill Rock.

This time it took nine years to undermine these obstacles, and on 10 October, 1885 General Newton’s daughter, Mary, pressed a key that simultaneously set off both sets of the charges. It was, “The greatest single explosion ever intentionally produced by man ”. Nine acres of East River bottom were pulverized. Columns of water rose 150 feet into the air. In that instant the Hells Gate became a safe passage for all ships, even excursion boats.

Captain Van Schaick failed in his attempt to run the General Slocum onshore on North Brother Island, instead grounding on a rock just off shore, still in eight to ten feet of water.

To people who did not know how to swim, and who were wearing layers of heavy wool clothing, anything over five feet of water was a near certain death sentence.

The fire continued to rage, the upper decks collapsing into the hull, until the semi-circle of boats which had followed the Slocum upstream realized all the cries for help from the water had gone still.

Only the crackle of flames and the lapping of bodies against the shore of North Brother Island could be heard. The air was heavy with the stench of burned wood and burnt flesh.

Then came the mad rush to save as many lives as possible.

Then the effort to comfort survivors, gathered outside the hospital on North Brother Island.

Then came the unpleasant duty of collecting the dead, washed up on the Island...

...or scattered along the East River like tear drops in the wake of the General Slocum.

At first they would be laid out on the hospital lawn

But as night began to fall they were moved inside a warehouse where family members could come to look for their missing family members. New York City would run out of coffins for the 1,021 dead - None of whom would have died if the Hell's Point had not been cleared for excursion boats.

In the final insult to the 321 survivors, the Captain Van Schaick jumped to a tugboat as soon as his ship grounded. He did not even get his feet wet.

Seven people were indicted by a Federal Grand Jury. Officers of the Knickerbocker Steamship Company were indicted but never charged and the company paid a small fine for falsifying inspection records. Shortly there after the owner sold off his ships and walked away, a very wealthy man.

Trials for the inspectors who had failed at their jobs all resulted in mistrials. Only Captain Van Schaick was convicted, two years after the disaster, of criminal negligence. He was sentenced to ten years in Sing Sing prison.

He was paroled by President Howard Taft in December of 1911, and he died in 1927, at the age of 91.

The burned out hulk of the General Slocum was converted into a coal barge and renamed the "Maryland". She sank in a squall south of Atlantic City, New Jersey in 1911.

In 1997, ninety years after the Slocum disaster, the oldest survivor, 104 year old Catherine Connelly, told a reporter, “If I close my eyes, I can still see the whole thing.” She passed on in 2002.

"Yes, sir. Terrible affair that General Slocum explosion. Terrible, terrible! A thousand causalities. And most heart rending scenes…Not a single life boat would float and the fire hose all burst…Graft, my dear sir. ..Where there’s money going there’s always someone to pick it up.”

James Joyce, “Ulysses”.

- 30 -

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please share your reaction.