I recently came across an old English music hall joke. A young Irish lad was warmly welcomed into an English pub , but after a few drinks the boy got a sad look. He explained he appreciated the comradeship, but missed his corner pub back home. “The first time you set foot in the place”, he explained , “they'd buy you a drink, then another, all the drinks you like. Then when you've finally had enough, they'd take you upstairs and make sure you get laid.”

The English patrons were skeptical, and the barkeep asked how many times the Irish lad had experienced this kind of welcome. “Never”, he admitted. “But it happened to my sister quite a few times.” Now I have to ask you, do you think that a racist joke? Sexist, yes. But racist? I suspect your answer depends on if you are Irish or not.

After almost thirty years of moderate success London Publisher James Henderson finally hit the mother lode in a penny tabloid weekly magazine, “Our Young Folks Weekly Budget”. Its 16 pages of action art work and adventure fiction dominated the youth market through various incarnations for 26 years.

(Henderson paid Robert Louis Stevens a pound per column for “Treasure Island”, which he serialized in “Young Folks”). And each noon, the savvy capitalist would meet with his editors, issuing detailed instructions for the flurry of newspapers and magazines – even a line of picture post cards - that cascaded from 169 Red Lion Court, Fleet street, each seeking to replicate “Young Folks” profits. Henderson had stumbled upon the concept of a targeted audiences.

A London Bobby asks two drunks for their names and addresses. The first answers, “I'm Paddy O'Day, of no fixed address.” And the second replies, “I'm Seamus O'Toole, and I live in the flat above Paddy.”

Beginning in 1831 royal taxes on newspapers were lowered by three-fourths. The response was instantaneous. New papers popped up like mushrooms after a rain. The industrial revolution was bringing people into the cities, and putting coins in their pockets. For the first time in history, that created consumers, which made advertising profitable (i.e. capitalism). More papers encouraged more people to read. By 1854, out of a population of 28 million, weekly newspaper sales in England had topped 122 million a year. In 1857 the last newspaper taxes were finally eliminated, triggering yet another wave – daily newspapers. It was this new customer vox populi that James Henderson and Sons were riding to success.

Paddy: Is your family in business? Seamus; Yes, iron and steel. My mother irons and my father steals

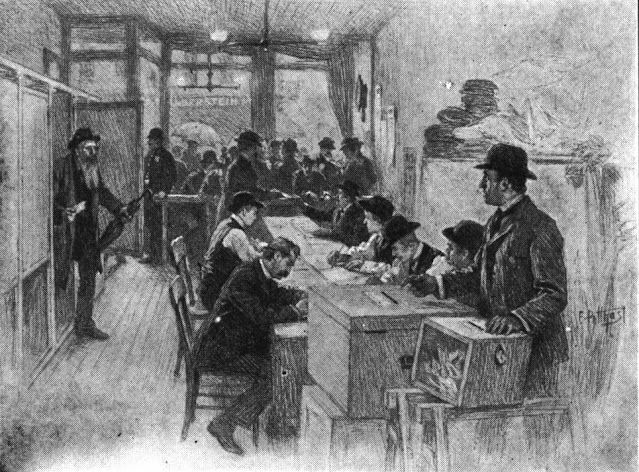

In December of 1874, Henderson created the first humor magazine in England, a sort of Victorian Daily Show in print, called “Funny Folks, The Comic Companion to the Newspaper”. The cover art for the first issue was drawn by John Proctor, who signed his work, “Puck”. “Funny Folks” proved so successful that Henderson released an entire line of humor magazines - “Big Comic”, “Lot-O-Fun” “Comic Life”, “Scraps and Sparks”. In 1892 came Henderson's most popular humor magazine, “Nuggets”

Bobby: “Madam, I could cite you for indecent exposure, walking down the street with your breast exposed like that.” Irish lass: “Holy Mary and Joseph, I left the baby on the bus.”

Like “Funny Folks”, Nuggets had its own featured artist, T.S. Baker, and his most popular creation was an Irish family living “in contented poverty” in South London - the Hooligans. The father, P. Hooligan, was a would-be entrepreneur, and shades of the 1950's Honeymooners TV show, a member of the Shamrock Lodge. And his every scheme in some way involved his wheelbarrow, and the family goat. Mrs. Hooligan was fashion conscious, but always copying far above her economic station. And there were, of course, a hoard of unnamed ginger haired children about.

It seems impossible to believe that the term hooligans, as in violent law breakers, practitioners of impractical anarchy, began as the name of a gentle Irish family imitating proper Victorian society. In the nine year run this cartoon Irish family, proved popular because it was drawn by an artist and comic writer of ingenious and subtle talents. In person the Hooligans don't make an obvious racist image. But what did the intended audience see in this cartoon, that a hundred plus years later, we might not? And how is being called a Paddy in 1890, different from being hit with the “N” word, today? Time and distance, I suspect.

What's the first thing an Irish lass does in the morning? She walks home

The bigotry towards Ireland seems to have started about a thousand years ago, with Gerald of Wales, the ultra-orthodox chaplain to the English King Henry II, who joined his monarch in the church endorsed invasion of Ireland, and with his observation of the locals. “This is a filthy people, wallowing in vice. They indulge in incest, for example in marrying – or rather debauching – the wives of their dead brothers.”

One would think a clergyman who had studied logic in Paris would have remembered Deuteronomy 25:5 - “...her husband's brother shall go in to her, and take her to him to wife, and perform the duty of a husband's brother to her.” I guess it's easier to butcher people, if you can manage to despise them for whatever reason. And imagine them as apes, be it the Irish or African Americans.

What do you call an Irishman with half a brain? Gifted

Illogically the English originally justified their oppression of the Irish because they were bringing them Catholicism. Then after their own Protestant reformation, the English used Catholicism to denigrate the Irish, calling them “cat licks” and “mackerel snappers” who ate fish on Fridays. With time the insults came to include local terrain (bog trotters) physical characteristics (carrot top), perceived laziness (narrow backs) and diet (potato heads, spud fuckers and tater tots for the children). Irish jokes (read insults) were standard fare in English music halls from the 1850's on, and always good for a laugh. And it was from this racism that the sophisticated simplicity of the Hooligans achieved something approaching an art form.

“What's the difference between an Irish wedding and an Irish wake? One drink.”

James Henderson, and his son Nelson, may have been racists. History has failed to record their opinions outside of the business decisions they made. And it may be valid to label them with the black mark because of the Hooligans. And they did publish worse. But then they were publishers, not social activists. And like a music hall comic who told Irish jokes, they provided the public what the public wanted, or else they could not remain in business. Morality is an affect, not an effect. So were these purveyors of anti-Irish humor racists, or were they merely businessmen? And did the Hooligans transcend racism because it was so well done? You might as well ask Norman Lear if Archie Bunker made life easier for African Americans by calling them “jungle bunnies” on national television. In fact that question has been asked

“Paddy, he said you weren't fit to associate with pigs, but I stuck up for you. I said you most certainly were.”

Its hard for me to dismiss the Hooligans because they make me smile, and because they were a loving respectful family, and because they were always striving. But mostly because they make me smile. Why I laugh at them, tells a story about me, not them. It is a lesson every artist must learn at some point, the sooner the better. What is put on the page, is rarely what is seen there. It is the job of the artist to limit confusion. But you can never be completely understood. The most you can consistently hope to achieve is to entertain. Enlightenment is the responsibility of the reader, not the writer.

Bobby; "Where were you born?" Paddy; "Dublin". Bobby; "What part?" Paddy; "All of me."

- 30 -

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)