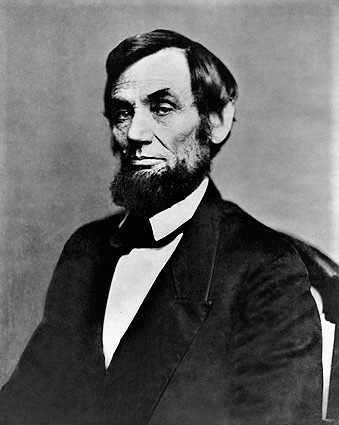

I hate the five dollar bill profile of Lincoln that most Americans hold. Abraham Lincoln saved the Union and ended slavery not because he was a saint but because he was the greatest politician who has ever occupied the White House.

And to those who despise “professional politicians”, my response is they have probably never seen a real professional in action. Such Pols don’t come along often, but when they do, they make the puny impersonations that must usually suffice seem like clowns.

And Lincoln’s professionalism was best displayed in his handling of the biggest clown in his cabinet, a man you have probably never heard of but whose best work you see every day of your life, Salmon Portland Chase (above). If Chase had been half as smart as he was ambitious, he would have been President instead of Lincoln. That to his dying day he continued to believe he deserved to be so, shows what a clown he really was.

Doris Kerns Goodwin has called Lincoln’s cabinet “A Team of Rivals”, but I think of it more as an obtuse triangle. At the apex was Lincoln (above, center). He was the pretty girl at the party. His suitors didn’t really want to know him, but they all wanted to have him.

On the inside track was the brilliant, obsequious William Seward (above) - the Secretary of State who thought of himself as Lincoln’s puppet master.

And the right angle was Salmon Chase (above), Secretary of the Treasury, born to money and brilliant, but with a stick up his alimentary canal.

And on Tuesday, 16 December, 1862 , the competition between these two paramours of Old Abe's banged heads in the head of Senator Charles Sumner (above), the Chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and leading Senatorial Cassandra.

Sumner had come into procession of a letter written by Seward to the American Ambassador to France. In the letter Seward complained that “…the extreme advocates for African slavery and its most vehement opponents are acting in concert together to precipitate a servile war, the former by making the most desperate attempts to overthrow the federal Union; the latter by demanding an edict of universal emancipation as a lawful and necessary if not, as they say, the only legitimate way of saving the Union.”

It was an old letter, and Seward's position had evolved, but to Sumner this passage was proof that behind the scenes Seward (above) was not fully committed to destroying slavery and the Confederacy. And it confirmed what he already heard from Chase.

Stephen Oates writes in “With Malice Toward None”, “…what bothered Chase the most was the intimacy between Lincoln and Seward…In talks with his liberal Congressional friends, Chase intimated that Seward was a malignant influence on the President...that it was (Seward) who was responsible for the administration’s bungling...Seward became a scapegoat for Republican discontent.” (pp 355-356)

Sumner convened what I call "The Magnificent Seven", the 7 most anti-slavery members of the Republican Senate caucus - called by their opponents and historians "Radical Republicans". Once the Seward letter was read out loud, Senator Ira Harris (above) from Albany, New York recorded the reaction.

“Silence ensued for several moments," wrote Harris, "when (Senator Morton Wilkinson of Minnesota (above)) said that in his opinion the country was ruined and the cause was lost…”

Senator William Fessenden (above) from Maine then added a bit of gossip. He'd been told by an unnamed member of the cabinet there was “…a secret backstairs influence which often controlled the apparent conclusions of the cabinet itself. Measures must be taken”, Fessenden concluded, “to make the cabinet a unity and to remove from it anyone who does not coincide heartily with our views in relation to the war.”

It is sad to say there was not a first rate mind in that room. There might have been, but arrogance drops a person’s I.Q. by forty points or more. Not one of the seven seems to have suspected they were being manipulated by Chase, that it was Chase who had whispered in Fesseneden's ear, and Wilkinsen' s ear as well, and even Sumner's. But each was convinced that they and they alone held the solution as to how to conclude the Civil War and end slavery. It is startling to think that men who used an outhouse every day, could be that arrogant.

They skewered up their courage for two days before saddling up and calling on the President at 7 P.M. on Thursday, 19 December, 1862. For three hours they harangued poor Mr. Lincoln on the dangers of Seward.

Lincoln remained agreeable but noncommittal, and proposed that they meet again the next night. And the amazing thing was that throughout that meeting Lincoln actually had William Seward’s resignation in his coat pocket.

Understand, Seward had not offered his resignation out of nobility. He was a politician. After hearing of the intentions of the Seven, Seward had a flunky deliver his resignation in private, as a back door demand that Lincoln pick the genial New Yorker over the prig from Ohio. Of course, the loss of support from New York would poke a fatal hole in Lincoln’s ship of state. So Seward was not expecting Lincoln to pick the prig for the poke.

Lincoln’s problem was he also needed the prig. Chase’s handling of the Treasury was brilliant. He was financing the entire war. It was Chase who had begun issuing official U.S. government backed paper currency, greenbacks (above). That had not been done since the American Revolution. It was Chase who had put the words “In God We Trust” on every bill, and it's still there today. Of course, Chase had also put his own face on every $1 bill (above), as a form of political advertising, but Lincoln was willing to tolerate that because Chase was honest in his job, and because without Ohio, the Union would lose the war.

The other factor was that the whispers about Seward’s “backstairs influence” were false. By December of 1862 it had dawned even on Seward that Lincoln was thinking for himself. When Lincoln had first read Seward's resignation - delivered by the portly Senator Preston King (above) - "remarkable for (his) obesity") - the President had exploded, and demanded to know, “Why will men believe a lie, an absurd lie, that could not impose upon a child, and cling to it, and repeat it, and cling to it in defiance of all evidence to the contrary?” Despite his anger, Lincoln knew the question was rhetorical.

But Lincoln's (above) frustration was understandable. He was beset by arrogance and delusion on all sides. It seemed that everybody in Washington thought they were smarter than Lincoln. But the skinny lawyer from Illinois was about to prove them all wrong.

At ten the next morning Lincoln told his cabinet about the previous night’s meeting. He made no accusations, he mentioned no names. But Chase immediately blubbered that this was the first he had heard about any of this matter. The President then asked them all, except Seward, to return that night to meet with the Seven.

Not invited, Seward (above) felt the ground giving way under his feet. He had never expected Lincoln might pick Chase over him. Now, suddenly, he did.

At the same time, Chase (above) was not entirely certain he had won.

That night the Seven became an audience, along with the cabinet sans Seward, to a bradavo performance. Gideon Welles (above), the Secretary of the Navy (then a cabinet office) recorded the festivities.

First, according to Welles, the President (above) “…spoke of the unity of his Cabinet, and how although they could not be expected to think and speak alike on all subjects, all had acquiesced in measures when once decided." At Lincoln's prompting, each cabinet member agreed with The President, specifically, "...Secretary Chase endorsed the President's statement fully and entirely…”

There were hours more of talking but right there, when Chase agreed with Lincoln, that was the end of "Chase's mutiny". As the Magnificent Seven were leaving the White House a stunned Senator Orville Hickman Browning (above) from Illinois asked how Chase could tell them that the cabinet was harmonious, after all his talk about division and the back stairs influence.

Charles Sumner(above) 's reply was simple and bitter. “He lied,” said Sumner. Chase was done as a malignant political influence in the cabinet. No Republican was going to believe anything he ever said again.

The next morning Lincoln called both Seward and Chase to the White House. Welles was again present, I suspect, as a witness for Lincoln. Wrote Lincoln's "Old Neptune", as he called Welles, “Chase said he had been painfully affected by the meeting last evening, which was a total surprise to him, and…informed the President he had prepared his resignation…“Where is it?” asked the President quickly, his eye lighting up in a moment."

“I brought it with me,” said Chase, taking the paper from his pocket…”Let me have it,” said the President, reaching his long arm and fingers towards Chase, who held on, seemingly reluctant…but the President was eager and…took and hastily opened the letter. “This," said he, looking towards me with a triumphal laugh, “cuts the Gordian knot.” An air of satisfaction spread over his countenance such as I have not seen for some time. “You may go to your Departments,” said the President;…(This) “is all I want…I will detain neither of you longer.” And with that both Chase and Seward left the oval office.

Both Seward and Chase spent a nervous night, not certain as to what Lincoln would do. They had both just been reminded who was in charge of this game. And it was not until a few days later that Lincoln sent a note to both Chase and Seward, saying that the nation could not afford to lose either of their talents. And it did not.

Seward never tried to pull Lincoln's strings again. But he played a vital part in ensuring passage of the XIII amendment to the constitution ending slavery for ever.

Seward barely survived an assasian's knife in the plot that murdered Lincoln, but continued to served President Andrew Johnson, even guiding him to acquire the Territory of Alaska (above) - which was labeled at the time "Seward's Folly". He served as Secretary of State until 8 March, 1869. Seward died in the afternoon of 10 October, 1872. His last words were "Love one another."

Salmon Portland Chase petulantly continued to resign annually until late October of 1864, when Lincoln no longer needed him to hold onto Ohio. But never one to waste talent, Lincoln took advantage of the death of that old racist Chief Justice Roger Taney, to nominate Chase to the Supreme Court.

Chase (above, center) was easily confirmed and sworn in on the same day as Chief Justice. His ego would not permit him to completely surrender his ambition, trying to achieve that office he was convinced he was so suited for, in 1868 as a Democrat and again in 1872 as a "Liberal Republican"

Chase (above) never resigned his position on the Supreme Court, dying of stroke on 7 May, 1873. His last vote on the court was in the minority, voting against the government's ability to regulate food safety.

So that is what it looks like when a skilled professional is on the job, using the best the troublesome foolish people who surround him or her have to offer to achieve great ends, like the end of slavery and the end of a civil war. It often sounds like confusion and pettiness at the time, but as newspaper editor,

John McNaught would note of a later American political crises, it is all "...just the American people washing their dirty linen in public."

To forestall the Supreme Court, on Sunday, 21 January, 1900, the directors of the Chicago Sanitary District tried to quietly produce another fait accompli (above). The Chicago Tribune explained why that did not prove a simple thing to achieve.

To forestall the Supreme Court, on Sunday, 21 January, 1900, the directors of the Chicago Sanitary District tried to quietly produce another fait accompli (above). The Chicago Tribune explained why that did not prove a simple thing to achieve. And the Chicago canal proved something else as well. As recorded by William C. Alden in the 1902 “Chicago Folio” for the U.S. Geological Survey Atlas of the United States (volume #81), excavations for the canal and its locks unearthed the history of the entire continent.

And the Chicago canal proved something else as well. As recorded by William C. Alden in the 1902 “Chicago Folio” for the U.S. Geological Survey Atlas of the United States (volume #81), excavations for the canal and its locks unearthed the history of the entire continent. Beneath the clay and beneath the limestone, the canal unearthed the bedrock of Chicago; “Potsdam Sand Stones”. So the bedrock of Chicago is petrified beach sand, the bottom of an ancient shallow sea. We know it was shallow because coals left their fossils in the sand and their lime rich skeletons (above) hundreds of feet thick embedded in the sand stones. Over millions of years that sea had been replaced with a freshwater lake, surrounded by trees, whose leaves fell into the waters, turning the waters acidic, and converting the top layer of the limestone into clay.

Beneath the clay and beneath the limestone, the canal unearthed the bedrock of Chicago; “Potsdam Sand Stones”. So the bedrock of Chicago is petrified beach sand, the bottom of an ancient shallow sea. We know it was shallow because coals left their fossils in the sand and their lime rich skeletons (above) hundreds of feet thick embedded in the sand stones. Over millions of years that sea had been replaced with a freshwater lake, surrounded by trees, whose leaves fell into the waters, turning the waters acidic, and converting the top layer of the limestone into clay. And then the glaciers had come, and scrapped across the clay, piling it up in a terminal moraine, which prevented the glacial melt waters from finding their way to the Mississippi river, until humans arrived and stood upon their own two feet of clay and thought, "I shall do this". And it was done. It was not done without a paying a price, but life requires a price be paid even if you decide to do nothing.

And then the glaciers had come, and scrapped across the clay, piling it up in a terminal moraine, which prevented the glacial melt waters from finding their way to the Mississippi river, until humans arrived and stood upon their own two feet of clay and thought, "I shall do this". And it was done. It was not done without a paying a price, but life requires a price be paid even if you decide to do nothing.