I often hear ultra right and left wing politicians called "fire brands". The original definition is a piece of kindling, a bit of burning wood used to start a larger fire. And those who start such fires for a living used to be called "Fire Eaters." It is a title you hear with increasing frequency, and yet it seems the advocates of fires have forgotten the agony they cause, eventually consuming the arsonists own home and life. And thus, a fire eater is also a perfect description of a dangerous ideologue. And the most famous fire eater and ideologue of American politics, one of the first self described political fire starters, was William Lowneds Yancey.

Yancey’s (above) South Carolina family were strongly pro-Federalist, and at an Independence Day celebration in 1834 the young man told a crowd, “Listen, not then...to the voice which whispers…that Americans…can no longer exist…citizens of the same republic…” He also championed the Federal Union as editor of the newspaper the “Greenville Mountaineer” - at least until 1835, when he married an Alabama widow with an Alabama plantation and 35 slaves. The ownership of human beings converted Yancey to pro-slavery. And then the economic panic of 1837 slashed cotton prices and wiped out William Yancey’s new found fortune and social status. This traumatic event also converted Yancy into a radical.

Yancey went back to the profession that he knew best, and in 1838 he bought a failing newspaper. Needing to make money quickly, Yancey's very first editorial was sure to please the money people of Alabama - a passionate defense of slavery. In a followup editorial he even favored reopening the slave trade with Africa, which had been closed down by British Naval patrols since 1819. Yancey publicly opposed the compromises of 1850, which sought to establish a balance between slave states and “free” states within the Union. By now anything short of total domination by slave states was a cowardly compromise, in Yancey’s view.

Also in 1838 the true nature of the man was revealed, when an alleged political insult led to a street brawl between Yancey and his wife’s uncle. Yancey shot the man dead on the street. He later justified this hot blooded murder, writing he had been, “Reared with the spirit of a man…and taught to preserve inviolate my honor…”, which seems to me like lousy justification for murder. He was convicted of manslaughter but served only a few months before being pardoned by the Governor. His reputation as a murderous hot head did nothing to prevent him from being elected to first the Alabama legislature and then, in 1844, to the U.S. House of Representatives.

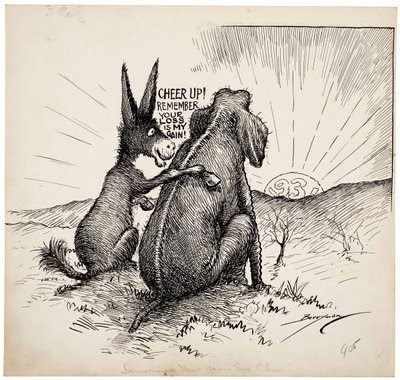

In 1858 Yancey wrote what Horace Greeley called, ‘The Scarlett Letter’, in which he invented the term "fire eater" to describe himself. He pledged that with like minded southerners, he would, “…fire the Southern heart – instruct the Southern mind - …and at the proper moment, by one organized, concerted action, we can precipitate the cotton states into revolution.” This was why Yancey was called the “Orator of Secession”. He worked hard to split his own (Democratic) party on the issue of slavery, believing the election of a Republican (anti-slavery) presidential candidate in 1860 would radicalize the south. He was, in the words of that genius Bruce Catton, “…one of the men tossed up by the tormented decade of the 1850’s (John Brown was another) who could help to bring catastrophe on but not do anything more than that.”

That the North had twice the population of the South, that the North had ten times the industrial and agricultural capacity, that slavery was already dying in the upper South, that the North would not fight to end slavery but would fight to preserve the union, that Lincoln did not believe the Federal government had the power or the right to outlaw slavery, all this meant nothing to Yancey. Yancey wanted secession not despite the destructive effects it would have on the South, but, it seemed, almost because of them. President-elect Abraham Lincoln described the problem of dealing with the fire eaters like Yancey. "Not only must we do them no harm, but somehow we must convince them that we mean to do them no harm". Does this sound anything like the "Do Nothing" Tea Party Congress of 2012 to 2016?

Once war broke out Jefferson Davis sent William Yancey (above) to England to seek recognition. A diplomatic mission seemed like an odd choice for this violent aggressive man, so perhaps Davis really had little hope of Britain ever recognizing the Confederacy, and he just wanted to be rid of Yancey. Lord Palmerston, the Prime Minister, eventually met with Yancey, but then asked if he had been serious about his call for a resumption of the slave trade. Yancey denied it, but as it was in print that merely made him an obvious liar. And just asking the question indicated there was no chance that England would recognize the South, at least as long as Yancey represented a significant political voice. Yancey returned home in frustration and defeat. He now served in the Confederate Senate, opposing Davis’ power to draft troops and blocking Davis’ attempt to form a Confederate Supreme Court in the spring of 1863.

It was during debate over the court when Yancey and Benjamin Hill of Georgia got into a brawl on the Confederate Senate floor. It was almost a repeat of the 1838 shooting. When the hot headed Yancy reached for his gun, Hill grabbed the only weapon he had at hand - an ink stand. He beaned Yancey on the head with it, cold cocking him. The Confederate Senate censured Yancey and took no action against Hill.

So it seemed that even his political allies and friends did not like William Yancey very much. And this was the man the South had staked its future upon. I believe it was William Yancey whom Jefferson Davis was thinking of when he said the epitaph of the Confederacy should be, “Died of a Theory.’

After censure, Yancey returned to Alabama, where he died in July of 1863, just 2 weeks before his 49th birthday. He had lived just long enough to see the twin defeats of Vicksburg and Gettysburg, which together sealed the doom of the Confederacy. But even then the fire eaters kept up their arson. More southerners died in the last year of the war, than in the previous 3 years.

The product of William Yancy's life’s work was the death of 750,000 young men and perhaps a million civilians - the vast majority of them southerners -: the total abolition of slavery in America and the ultimate victory of Federalism over State’s Rights. It is an estate today's fire eaters of the Republican Party ought to take note of. But I doubt they will.

- 30 -