I keep reading that the election of 1884 was one of the “dirtiest” in American history, which strikes me as saying that a sewer is dirtier than a septic tank. Still I have to admit that there was a lot of mud flung around by James Blaine and Grover Cleveland. And as usual, he who flung the most, won. Blaine got in the first shot.

The Democratic convention in Buffalo, New York ended on 11 July 1884, after having nominated hometown hero, “Honest” Grover “The Good” Cleveland. Just ten days later the “Buffalo Evening Telegraph” reported “A Terrible Tale”; that in 1874 Cleveland had an affair with a young widow from New Jersey named Maria Helpin. That September Mrs. Helpin had given birth to a son she named Oscar Folsom Cleveland (Folsom was the name of Cleveland’s law partner). According to the “Telegraph”, Maria ended up in an asylum and the poor innocent boy had ended up in an orphanage. The Republican faithful began the chant, “Ma, Ma, where’s my Pa? Gone to the White House, ha, ha, ha.”

It was a great story, and parts of it were true. But Cleveland (above) refused to panic and instructed his followers to “Just tell the truth”, which is easy to say at those rare times when the truth actually helps you. The truth was that Mrs. Helpin had affairs with several men (something that probably happened a lot more often than anyone in 1884 was willing to publicly admit), and there were several men who might have been the father of her child. Cleveland never admitted parentage. But he had supported the infant after Maria started drinking. Later, when it became clear Maria was not going to get sober anytime soon, Cleveland had paid her $500 to give up Oscar, and the boy was adopted by a friend of Cleveland’s, and eventually ended up graduating from medical school. So, after all of those details came out, the initial Blaine attack had resulted in Cleveland sounding more honest than before. The second Blaine attack backfired even worse.

There were two “third parties” in 1884; the Greenback Party and the Prohibition Party. The Greenback Party seemed likely to hurt the Democrats most, so Blaine’s Republican supporters actually gave them money. “The Dry’s” had nominated for President John St. John (above), three time governor of Kansas. Blaine’s people were worried that St. John would siphon off Republican votes in upstate New York. They urged St. John to drop out of the race, and when he refused they spread the story that St. John had abandoned a battered wife and child in California. Again, the smear was true, sort of. After his parents had died (when St. John was 15) he had joined the ‘49ers, looking for his fortune in the gold fields. He didn’t find gold but at the age of 19 he had found a wife and fathered a child. And at his wife’s request he had “granted” her, to use the old phrase, a divorce, before returning, broke, back to to Illinois.

Like most smears this one hurt St. John the most among his most fervent supporters. Prohibitionists were always a priggish bunch of humorless unforgiving bores, and they abandoned St. John as if they had just discovered the sacramental wine was actual wine. But St. John had that other trait you often find in prohibitionists; he considered revenge a matter of principle. Knowing he now stood no chance of even winning Kansas, St. John concentrated his efforts in upstate New York, just the place the Republicans were the most worried about.

Meanwhile, James Blaine, the Republican candidate, had his own problems, with the “Mugwumps”. This was yet another group of holier than thou Victorian prigs, but these prigs were Republicans, and they had a hard time deciding whether or not to support Blaine because he was so…well, crooked. They took their name from a supposed Algonquin word for “big leader”, but it was "New York Sun" columnist Charles Dana who defined them as Republicans who had their “mugs” on one side of the fence and their “wumps” on the other. Republican commentators went so far as to imply that the Mugwumps were “effete”, or to use the 1884 vernacular, “Man millners”, or the 2017 vernacular, homosexuals.

Meanwhile the Democrats were throwing everything they could think of at "James Blaine, the Continental Liar From the State of Maine", such as calling him "Slippery Jim". They dragged up the old charge of “Burn this letter after reading”. And the Indianapolis Sentinel even discovered that Blaine had married his wife only after her father had threatened him with a shotgun. Blaine sued for liable but the paper then produced the certificates showing the couple had been married in March, 1851 and their first child had been born less than three months later. Unheard of! A young couple had engaged in sex before they were married! Shocking! Blaine came up with a story about two ceremonies, one private in 1850, and a public wedding a year later, but by the time he finished explaining it all, the audience had turned to the comic pages.

But the final nail in Blaine’s coffin was supposedly driven in by the Reverend Samuel Burchard, who at a New York City Republican rally, with Blaine sitting at the dais, charged that the Democrats stood for “Rum, Romanism, and Rebellion”. The press had a field day, calling the phrase anti-southern and anti-Catholic, (which it was) and that by his silence Blaine had approved of it. But that last part was absurd. Blaine’s mother was a practicing Catholic. His sister was a nun. The Republicans had even been hoping to attract some Catholic votes away from the Democrats. But none of that mattered to the press, or to the Democrats who publicly organized Catholic Democratic lawyers in case they had to contest the official election results from New York. And they almost did.

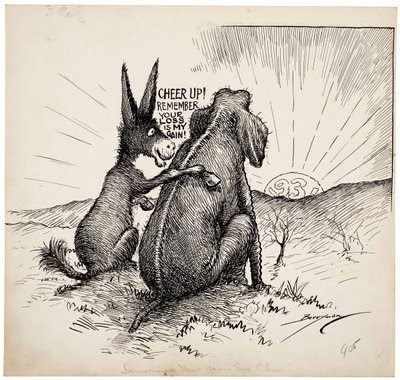

In the end it is difficult to say precisely why Cleveland won and Blaine lost. The popular vote cast on Election Day, Tuesday, 4 November 1884, was four million eight hundred seventy-four thousand for Cleveland (48.5%) and four million eight hundred forty-eight thousand (48.2%) for Blaine. But as we all know the popular vote is meaningless. What counted was the Electoral College, and there Cleveland won two hundred nineteen votes to one hundred eighty-two for Blaine, giving Cleveland a 37 electoral vote victory. The difference was New York State’s 36 votes which Cleveland won by a mere 1,047 votes out of one million one hundred twenty-five thousand and forty-eight votes cast in the Empire state. I think what made those 1,047 votes so powerful were the twenty-four thousand nine hundred ninety-nine votes cast in up[state New York for Prohibitionist Party candidate John St, John. It may have been the last time a prohibitionist could proudly say, “Here’s mud in your eye” - to James Blaine, the Continental Liar from the State of Maine.

The Democratic convention in Buffalo, New York ended on 11 July 1884, after having nominated hometown hero, “Honest” Grover “The Good” Cleveland. Just ten days later the “Buffalo Evening Telegraph” reported “A Terrible Tale”; that in 1874 Cleveland had an affair with a young widow from New Jersey named Maria Helpin. That September Mrs. Helpin had given birth to a son she named Oscar Folsom Cleveland (Folsom was the name of Cleveland’s law partner). According to the “Telegraph”, Maria ended up in an asylum and the poor innocent boy had ended up in an orphanage. The Republican faithful began the chant, “Ma, Ma, where’s my Pa? Gone to the White House, ha, ha, ha.”

It was a great story, and parts of it were true. But Cleveland (above) refused to panic and instructed his followers to “Just tell the truth”, which is easy to say at those rare times when the truth actually helps you. The truth was that Mrs. Helpin had affairs with several men (something that probably happened a lot more often than anyone in 1884 was willing to publicly admit), and there were several men who might have been the father of her child. Cleveland never admitted parentage. But he had supported the infant after Maria started drinking. Later, when it became clear Maria was not going to get sober anytime soon, Cleveland had paid her $500 to give up Oscar, and the boy was adopted by a friend of Cleveland’s, and eventually ended up graduating from medical school. So, after all of those details came out, the initial Blaine attack had resulted in Cleveland sounding more honest than before. The second Blaine attack backfired even worse.

There were two “third parties” in 1884; the Greenback Party and the Prohibition Party. The Greenback Party seemed likely to hurt the Democrats most, so Blaine’s Republican supporters actually gave them money. “The Dry’s” had nominated for President John St. John (above), three time governor of Kansas. Blaine’s people were worried that St. John would siphon off Republican votes in upstate New York. They urged St. John to drop out of the race, and when he refused they spread the story that St. John had abandoned a battered wife and child in California. Again, the smear was true, sort of. After his parents had died (when St. John was 15) he had joined the ‘49ers, looking for his fortune in the gold fields. He didn’t find gold but at the age of 19 he had found a wife and fathered a child. And at his wife’s request he had “granted” her, to use the old phrase, a divorce, before returning, broke, back to to Illinois.

Like most smears this one hurt St. John the most among his most fervent supporters. Prohibitionists were always a priggish bunch of humorless unforgiving bores, and they abandoned St. John as if they had just discovered the sacramental wine was actual wine. But St. John had that other trait you often find in prohibitionists; he considered revenge a matter of principle. Knowing he now stood no chance of even winning Kansas, St. John concentrated his efforts in upstate New York, just the place the Republicans were the most worried about.

Meanwhile, James Blaine, the Republican candidate, had his own problems, with the “Mugwumps”. This was yet another group of holier than thou Victorian prigs, but these prigs were Republicans, and they had a hard time deciding whether or not to support Blaine because he was so…well, crooked. They took their name from a supposed Algonquin word for “big leader”, but it was "New York Sun" columnist Charles Dana who defined them as Republicans who had their “mugs” on one side of the fence and their “wumps” on the other. Republican commentators went so far as to imply that the Mugwumps were “effete”, or to use the 1884 vernacular, “Man millners”, or the 2017 vernacular, homosexuals.

But the final nail in Blaine’s coffin was supposedly driven in by the Reverend Samuel Burchard, who at a New York City Republican rally, with Blaine sitting at the dais, charged that the Democrats stood for “Rum, Romanism, and Rebellion”. The press had a field day, calling the phrase anti-southern and anti-Catholic, (which it was) and that by his silence Blaine had approved of it. But that last part was absurd. Blaine’s mother was a practicing Catholic. His sister was a nun. The Republicans had even been hoping to attract some Catholic votes away from the Democrats. But none of that mattered to the press, or to the Democrats who publicly organized Catholic Democratic lawyers in case they had to contest the official election results from New York. And they almost did.

In the end it is difficult to say precisely why Cleveland won and Blaine lost. The popular vote cast on Election Day, Tuesday, 4 November 1884, was four million eight hundred seventy-four thousand for Cleveland (48.5%) and four million eight hundred forty-eight thousand (48.2%) for Blaine. But as we all know the popular vote is meaningless. What counted was the Electoral College, and there Cleveland won two hundred nineteen votes to one hundred eighty-two for Blaine, giving Cleveland a 37 electoral vote victory. The difference was New York State’s 36 votes which Cleveland won by a mere 1,047 votes out of one million one hundred twenty-five thousand and forty-eight votes cast in the Empire state. I think what made those 1,047 votes so powerful were the twenty-four thousand nine hundred ninety-nine votes cast in up[state New York for Prohibitionist Party candidate John St, John. It may have been the last time a prohibitionist could proudly say, “Here’s mud in your eye” - to James Blaine, the Continental Liar from the State of Maine.

- 30 -