"…full of sound and fury, signifying nothing." Macbeth; Act V, scene v

*****************************************************************

I wonder if there has ever been a good reason for a riot? The dictionary says a riot is “a violent disturbance of the peace by three or more persons”, but that definition doesn’t seem to really define the subject fully. The “Zip to Zap” riot of 1969 remains the only public disorder in North Dakota history, but the primary violation of public order there seems to have been ‘group vomiting in public’. The Sydney Cricket riot of 1879 consisted of 2,000 outraged Aussies rushing the “pitch” and stripping the shirts off two English players; the entire “riot” took less than 20 minutes. And the English “Calendar Riots” of 1751 are the answer to the question, “What if they held a riot and nobody came?” But of all the stupid reasons to have a riot, the stupidest, the dumbest and the single silliest reason has to be because you found an actor’s rendition of Macbeth was “too English”.

"I bear a charmed life". Macbeth: Act V, scene viii

*****************************************************************

This stupidity began in 1836 with a then 20 year old athletic stone-headed ego maniac from Philadelphia named Edwin Forrest. He was a sort of full-back version of the “Lord of the Dance”, Michael Flatley. Humbly, Forrest described himself as “…a Hercules.” As an actor, “…baring his well-oiled chest and brawny thighs…” Forrest milked every ounce of histrionics out of “Henry V” and every pound of pathos out of “King Lear”, bounding about the stage to liven up the "slow" parts of Shakespeare. By the time he was twenty, Forrest was earning $200 at day (today’s equivalent would be $4,000). Then Forrest decided to conquer the London stage, and parenthetically to study at the foot of the giant of Victorian Shakespearean over- actors, Edward Kean.

“If you can look into the seeds of time, and say which grain will grow and which will not, speak” Macbeth; Act I, scene iii

*******************************************************************

Forrest was a minor hit in London playing supporting roles. While in town he wined and dinned the other giants of the English stage, Charles Kemble and William Charles Macready, and paid them homage. And as a memento of his trip, Forrest took home an English wife, the lovely and wise Catherine Norton Sinclair.

Forrest's return to America was greeted with packed houses and raves by most reviewers. There were some voices of dissent, such as William Winter, who wrote for the New York Tribune that Forrest behaved on stage like a maddened animal “bewildered by a grain of genius”. But such discontent was drowned out in the applause from Boston to Denver. American audiences liked their actors larger than life in those days, and Forrest was just about as large as he could get. In fact, everything would have been perfect but for two small details. First, Edwin could not resist sharing himself with every woman who swooned at his manly thighs (the vast numbers of whom Catherine had a little trouble dealing with), and second, Edwin decided to make a triumphal return tour of England in 1845.

"Fair is foul, and foul is fair". Macbeth: Act I, scene i.

*******************************************************************

Forrest opened at the Princess’s Theatre in London, where he billed himself as “The Great American Shakespearean Actor”. That was his first mistake. Importing leading Shakespearean actors to England is like bringing coals to Newcastle; they don’t really need any more. When Forrest performed his Macbeth, the audience had the audacity to “boo”. Forrest then made his second mistake when he decided that the negative reaction was a conspiracy hatched by William Macready.

"What 's done is done" Macbeth: Act III, scene ii

******************************************************************

Oddly enough Macready (above) respected Forrest, even though their acting styles were diametrically opposed. Macready even thought of them as friends. Which only made Macready all the more shocked when, during his “to be or not to be” speech in Edinburg, he discovered that the foulmouthed baboon hissing at him from a private box adjacent to the stage was none other than his erstwhile friend, Edwin Forrest. Forrest even wrote to the “London Times” to justify his gauche behavior as every audience members’ right to critique a performer on the spot. That lit up the press from Leadville, Colorado to Inverness, Scotland. Every yahoo had an opinion as to who was the more objectionable, the vulgar American, or the stuck up Limey.

“Let not light see my black and deep desires” Macbeth; Act I scene iv

*******************************************************************

In 1849, when Macready, “The Eminent Tragedian”, began what he intended as his farewell tour of America, he found that Forest (above) had sown salt ahead of him. At every major city he played, from New Orleans to Cleveland, Forest was headlining in another local theatre, performing the same plays.

When Macready opened on May 7th in “Macbeth” at the Astor Place Opera House in Manhattan, Forrest was opening in “Macbeth” at another theatre just a mile away. And the instant that Macready stepped from the wings that first night it was, in the words of a modern critic, “Groundlings, garb your tomatoes!” The audience began to boo, and then to throw things. After a chair just missed beheading Macready, he took a quick bow and ran for the wings.

“...When the battle 's lost and won". Macbeth: Act I, Scene i

*******************************************************************

If the troubles had ended there it would have been a mere footnote in theatrical history. But the next morning Washington Irving and Herman Melville stuck their gigantic egos into the mess. They circulated and published a petition signed by 47 ‘distinguished’ New Yorkers begging Macready to stay for just one more performance. Against his own better judgment, and facing threats of lawsuits if he quit early, Macready agreed to one more show.

“If chance will have me king, why, chance may crown me.” Macbeth; Act I, scene iii

*******************************************************************

Overnight handbills blossomed on every lamppost in the Bowery; “Workingmen! Shall Americans or English rule this city?” The question was posed by something called “The American Committee”, obviously not a bulwark of artistic objectivity. But I still wonder who really paid for those posters? The city fathers ordered up 325 policemen, and called up 200 members of the 7th regiment, New York Volunteers, to guard the Opera House. And they needed them. On Thursday, May 10, 1849 the troublemakers were kept out of the theatre, but perhaps 10,000 future New York Yankee fans gathered across Astor Place hurling first insults at the cops, and then moving on to rocks and bricks. Eventually the shower of stone shattered the plywood that protected the theatre’s windows and audience members inside were dodging missiles bouncing between their seats.

“Is this a dagger which I see before me?” Macbeth; Act II, scene i

******************************************************************

Then the crowd charged the cops. The cops beat them back: twice. A handful of “Bowery Boys” tried to set the Opera House on fire. And the next time the crowd charged the police, the 200 members of the 7th let loose a volley. When the smoke cleared, some 22 to 30 people were dead and more than 100 wounded, including some police officers. As at Kent State a century and a half later, many of those shot were innocent bystanders. But enough of the troublemakers had been scared enough to leave Astor Place. The Shakespeare Riot was over.

"All the perfumes of Arabia will not sweeten this little hand.” Macbeth Act V, Scene i.

********************************************************************

It would be comforting to say that Edwin Forrest suffered for his egomaniacal gambling with other people’s lives. But he didn’t. He just got more famous and more popular. And in 1850 Edwin even had the gall to sue Catherine for divorce, charging her with adultery.

Yes, the biggest horn dog in America was claiming his English wife had been unfaithful to him. She hadn’t. But the press - on both sides of the Atlantic - published every nasty innuendo and allegation. In the end, Justice Thomas J. Oakley awarded Catherine her freedom and required Edwin Forrest to pay her $3,750 (the equivalent of $92,000 today) every year for the rest of her life. It doesn’t appear as if Edwin really missed the money because he never paid it. True to his character he simply avoided New York State and kept his fortune. And when he died in 1876, alone in his Philadelphia mansion, most of his estate went to Catherine because of unpaid alimony. At least she outlived the old jerk.

“Nothing in his life became him like the leaving it.” Macbeth: Act I, scene iv.

*******************************************************************

It all brings to mind the old English music hall ditty, “…They jeered me; they queered me, and half of them stoned me to death. They threw nuts and sultanas, fired eggs and bananas, the night I appeared as Macbeth.”

- 30 –

It was at this point in the evolution of the idea that chance intervened, in the form of a love sick 22 year old woman in far off Bristol, England. On May 8, 1885 Miss Sara Ann Henley received a note from her boyfriend breaking off their engagement. In a fit of pique Miss Henley walked half way across the Clifton Suspension Bridge, above the Avon River Gorge, and threw herself off. As she plummeted the 245 feet toward oblivion her crinolined petticoats caught the air like a parachute and slowed her descent. Luckily she landed in shallow waters along the shore, where her landing was softened by thick forgiving mud. She was badly injured, but she lived. Her extraordinary survival made all of the English papers, and was picked up and republished in America.

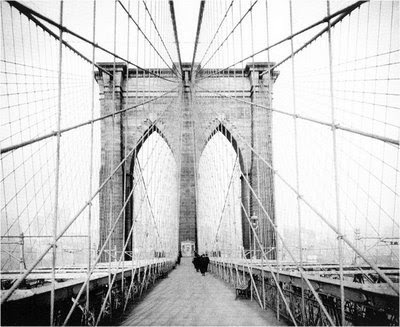

It was at this point in the evolution of the idea that chance intervened, in the form of a love sick 22 year old woman in far off Bristol, England. On May 8, 1885 Miss Sara Ann Henley received a note from her boyfriend breaking off their engagement. In a fit of pique Miss Henley walked half way across the Clifton Suspension Bridge, above the Avon River Gorge, and threw herself off. As she plummeted the 245 feet toward oblivion her crinolined petticoats caught the air like a parachute and slowed her descent. Luckily she landed in shallow waters along the shore, where her landing was softened by thick forgiving mud. She was badly injured, but she lived. Her extraordinary survival made all of the English papers, and was picked up and republished in America. A week after Miss Henley’s great fall the New York police got word that ‘Professor’ Odlum had been inspired to give the Brooklyn bridge another “go”. They alerted the toll collectors, and on Sunday afternoon, May 19, 1885 (ten days after Miss Henley’s plunge) a collector reported a suspicious cab lingering on the bridge. Officers found it parked against the outside rail half way across the span. But it was a decoy. While they were searching the cab, two wagons further back "Professor" Odlum leapt from beneath a covered flatbed wearing a swimsuit emblazoned with his name, clambered over the railing and before the cops could reach him, threw him self into space.

A week after Miss Henley’s great fall the New York police got word that ‘Professor’ Odlum had been inspired to give the Brooklyn bridge another “go”. They alerted the toll collectors, and on Sunday afternoon, May 19, 1885 (ten days after Miss Henley’s plunge) a collector reported a suspicious cab lingering on the bridge. Officers found it parked against the outside rail half way across the span. But it was a decoy. While they were searching the cab, two wagons further back "Professor" Odlum leapt from beneath a covered flatbed wearing a swimsuit emblazoned with his name, clambered over the railing and before the cops could reach him, threw him self into space. Imagine Robert Odlum’s surprise when he discovered that the cops had been right. He entered the water feet first (as was the accepted diving position at the time) and shattered every bone in his frame from heel to skull. He was pulled from the river unconscious and died a half hour later. His friends shipped his body home, and Robert’s sister came to town ten days later to demand that the coroner explain what had become of her brother’s liver and heart. She never got a satisfactory answer, but my guess is they had both been reduced to jelly by the impact. A little math shows that “Professor” Odlum hit the water going sixty-three and a half miles an hour. At that speed water is as fluid as cold concrete.

Imagine Robert Odlum’s surprise when he discovered that the cops had been right. He entered the water feet first (as was the accepted diving position at the time) and shattered every bone in his frame from heel to skull. He was pulled from the river unconscious and died a half hour later. His friends shipped his body home, and Robert’s sister came to town ten days later to demand that the coroner explain what had become of her brother’s liver and heart. She never got a satisfactory answer, but my guess is they had both been reduced to jelly by the impact. A little math shows that “Professor” Odlum hit the water going sixty-three and a half miles an hour. At that speed water is as fluid as cold concrete. But it was Robert Odlum’s tragic foolishness that was the catalyst for the Irish hero of our bad idea. He was 23 years old by this time making his living as a newsboy and a bookie amongst the denizens of the Bowery. Like a certain actress he had worked with, Steve Brodie needed to escape the chorus, except in his case the chorus was a carcophony of poverty. The story that he later told was that a friend, James Brennan, had dared him on a $100 bet that he would not jump off the Brooklyn Bridge, and survive. But I doubt that Mr. Brennan had ever seen $100 in his life.

But it was Robert Odlum’s tragic foolishness that was the catalyst for the Irish hero of our bad idea. He was 23 years old by this time making his living as a newsboy and a bookie amongst the denizens of the Bowery. Like a certain actress he had worked with, Steve Brodie needed to escape the chorus, except in his case the chorus was a carcophony of poverty. The story that he later told was that a friend, James Brennan, had dared him on a $100 bet that he would not jump off the Brooklyn Bridge, and survive. But I doubt that Mr. Brennan had ever seen $100 in his life.

Brodie parleyed his 15 minutes of fame into his own bar, with a little theatre in the rear where he re-enacted his alledged dramatic plunge into the East River several times a week for the tourists. In 1891 promoters built a Broadway melodrama (“Mad Money”) around his dive and another in 1894, (“On the Bowery”).

Brodie parleyed his 15 minutes of fame into his own bar, with a little theatre in the rear where he re-enacted his alledged dramatic plunge into the East River several times a week for the tourists. In 1891 promoters built a Broadway melodrama (“Mad Money”) around his dive and another in 1894, (“On the Bowery”).

In 1895 Mrs. Clara McArthur, married to a disabled railroad worker and mother to a young daughter, jumped off the bridge at 3:30 in the morning. She was seeking a share of Steve Brodies’ pot of gold for her destitute family. The desperate Clara was wrapped in an American flag. She had water-wings strapped under her arms and a punching bag tied to her back to keep her afloat after landing. Her socks were filled with sand to keep her feet below her head (again the accepted best attitude to enter the water). But she hit the water on her side, spreading the impact over the length of her body. Still, the impact ripped the water wings under her arms, to shreds. She struggled to the surface but the punching bag kept flipping her over, onto her face, and the socks kept pulling her down. Clara finally passed out, face down in the water.

In 1895 Mrs. Clara McArthur, married to a disabled railroad worker and mother to a young daughter, jumped off the bridge at 3:30 in the morning. She was seeking a share of Steve Brodies’ pot of gold for her destitute family. The desperate Clara was wrapped in an American flag. She had water-wings strapped under her arms and a punching bag tied to her back to keep her afloat after landing. Her socks were filled with sand to keep her feet below her head (again the accepted best attitude to enter the water). But she hit the water on her side, spreading the impact over the length of her body. Still, the impact ripped the water wings under her arms, to shreds. She struggled to the surface but the punching bag kept flipping her over, onto her face, and the socks kept pulling her down. Clara finally passed out, face down in the water.

Steve Brodie is not counted as one of those ten. He was always an agreable fellow. If he had money, his friends and family shared in it. He gave generously to charity his entire life. But it is extremely doubtful that he actually made the jump. He tried to extend his fame by claiming to have lepted off a railroad bridge in upstate New York, and later claiming to have gone over Niagara Falls wrapped in inner tubes and metal bumpers. The Niagara stunt, real or not, almost killed him. He settled in Buffalo, New York, and operated a bar there for a few years before his asthma forced him to move to San Antonio, Texas, where he died in 1901 of complications of diabetes. Steve Brodie was all of 38 years old. He is buried in Calvary Cemetery, in Woodside, Queens, New York. Thankfully the idea of jumping from the bridge for fame and fortune died with him.

Steve Brodie is not counted as one of those ten. He was always an agreable fellow. If he had money, his friends and family shared in it. He gave generously to charity his entire life. But it is extremely doubtful that he actually made the jump. He tried to extend his fame by claiming to have lepted off a railroad bridge in upstate New York, and later claiming to have gone over Niagara Falls wrapped in inner tubes and metal bumpers. The Niagara stunt, real or not, almost killed him. He settled in Buffalo, New York, and operated a bar there for a few years before his asthma forced him to move to San Antonio, Texas, where he died in 1901 of complications of diabetes. Steve Brodie was all of 38 years old. He is buried in Calvary Cemetery, in Woodside, Queens, New York. Thankfully the idea of jumping from the bridge for fame and fortune died with him. The longest living survivor of all these daredevils was the accidental one. Sara Ann Henley (below), the woman who tried to commit suicide in 1885 by jumping 240 feet off the Clifton Suspension bridge, finally earned her angel’s wings in 1948. She was 84 years old, married but with no children, perhaps because of injuries sustained in her fall into the Avon River Gorge. Such feats, for fame or to protest fortune, are never good ideas.

The longest living survivor of all these daredevils was the accidental one. Sara Ann Henley (below), the woman who tried to commit suicide in 1885 by jumping 240 feet off the Clifton Suspension bridge, finally earned her angel’s wings in 1948. She was 84 years old, married but with no children, perhaps because of injuries sustained in her fall into the Avon River Gorge. Such feats, for fame or to protest fortune, are never good ideas.

At 7:48 a.m. on December 7, 1941, out of a clear blue sky, 353 Japanese bombers, torpedoe planes and fighters of the first wave began their attack on Pearl Harbor. The United States Pacific fleet was caught flat footed, unprepared, with our war planes on the ground. How could we have been caught so unprepared if not by a conspiracy?

At 7:48 a.m. on December 7, 1941, out of a clear blue sky, 353 Japanese bombers, torpedoe planes and fighters of the first wave began their attack on Pearl Harbor. The United States Pacific fleet was caught flat footed, unprepared, with our war planes on the ground. How could we have been caught so unprepared if not by a conspiracy?

Just an hour later, as the first wave of Japanese planes banked to return to their carriers, they left behind 8 ships sunk in Darwin harbor. They had damaged a dozen other ships (including a hospital ship), destroyed the limited harbor facilities, as well as destroying 10 P-40 fighters, one B-24 bomber, 3 C-45 transports, 3 PBY flying boats and 6 Lockheed Hudson Australian Bombers, as well as knocking out Darwin’s electricity and fresh water systems, and killing at least 243 military personnel and civilians and wounding 200 more. The Darwin raid has been called “Australia’s Pearl Harbor”. How were the Japanese able to achieve another surprise attack after so many warnings?

Just an hour later, as the first wave of Japanese planes banked to return to their carriers, they left behind 8 ships sunk in Darwin harbor. They had damaged a dozen other ships (including a hospital ship), destroyed the limited harbor facilities, as well as destroying 10 P-40 fighters, one B-24 bomber, 3 C-45 transports, 3 PBY flying boats and 6 Lockheed Hudson Australian Bombers, as well as knocking out Darwin’s electricity and fresh water systems, and killing at least 243 military personnel and civilians and wounding 200 more. The Darwin raid has been called “Australia’s Pearl Harbor”. How were the Japanese able to achieve another surprise attack after so many warnings? At 6:20 a.m. on the morning of April 18, 1942 (now 102 days since the Pearl Harbor attack) Japanese Vice Admiral Boshiro Hosogaya, commander of the Japanese Fifth Fleet aboard the heavy cruiser Kiso, was awakened to read an urgent message from picket boat Number 23, the Nitto Maru. The message read; “Three enemy carriers sighted -Position 650 nautical miles east of Inubo Saki.” The Nitto Maru failed to respond to calls for further information. The vice-admiral alerted the command of the Combined Fleet headquarters. He advised them that with the known range of American carrier based bombers, the Americans would not be within range to attack the home islands for another 24 hours. The combined fleet immediately sent the following message to all commands; “Tactical Method 3 against United States Fleet.” In response elements of the First and Second Fleets sortie-ed out of their bases at Yokosuka and Hiroshima and began searching for the American carriers. Japanese aircraft carriers as far away as the Indian Ocean began to steam at all possible speed toward home waters. They would not be in time.

At 6:20 a.m. on the morning of April 18, 1942 (now 102 days since the Pearl Harbor attack) Japanese Vice Admiral Boshiro Hosogaya, commander of the Japanese Fifth Fleet aboard the heavy cruiser Kiso, was awakened to read an urgent message from picket boat Number 23, the Nitto Maru. The message read; “Three enemy carriers sighted -Position 650 nautical miles east of Inubo Saki.” The Nitto Maru failed to respond to calls for further information. The vice-admiral alerted the command of the Combined Fleet headquarters. He advised them that with the known range of American carrier based bombers, the Americans would not be within range to attack the home islands for another 24 hours. The combined fleet immediately sent the following message to all commands; “Tactical Method 3 against United States Fleet.” In response elements of the First and Second Fleets sortie-ed out of their bases at Yokosuka and Hiroshima and began searching for the American carriers. Japanese aircraft carriers as far away as the Indian Ocean began to steam at all possible speed toward home waters. They would not be in time.

Ten targets were struck in Tokyo by the B-25 meidum range land based bombers, and one each in four other Japanese cities. A carrier under construction was hit by a single bomb. One bomb even landed inside the grounds of the Imperial Palace. Of the attackers, one B-25 received some minor damage from anti-aircraft fire, and another had to dump its load into the sea when it was attacked by fighters. The two American carriers that had launched The Doolittle Raid, and all escorting ships, escaped unharmed. It would be weeks before the American public was informed of the attack, but the Japanese responded immediately by diverting fighter squadrons and anti-aircraft units back to the home islands, and with more extreme measures. Long before another American bomb landed on Japan, 10% of Tokyo had been plowed under to form fire brakes across the city, which proved ineffectual in the B-29 fire raids of 1945.

Ten targets were struck in Tokyo by the B-25 meidum range land based bombers, and one each in four other Japanese cities. A carrier under construction was hit by a single bomb. One bomb even landed inside the grounds of the Imperial Palace. Of the attackers, one B-25 received some minor damage from anti-aircraft fire, and another had to dump its load into the sea when it was attacked by fighters. The two American carriers that had launched The Doolittle Raid, and all escorting ships, escaped unharmed. It would be weeks before the American public was informed of the attack, but the Japanese responded immediately by diverting fighter squadrons and anti-aircraft units back to the home islands, and with more extreme measures. Long before another American bomb landed on Japan, 10% of Tokyo had been plowed under to form fire brakes across the city, which proved ineffectual in the B-29 fire raids of 1945.  The common thread connecting these three nations from December 1941 to April 1942 was the assumption that war could be restrained by the plans of politics or strategy. But all wars appear out of a clear blue sky, even to those who start them. And no strategy survives the first contact with the enemy. So all wars are a form of compulsory education for those foolish enough to think they have nothing to learn. And the three lesson that war teaches are always the same. The only sin in war is losing. The only assurance of losing is arrogance. And arrogance always leads to war.

The common thread connecting these three nations from December 1941 to April 1942 was the assumption that war could be restrained by the plans of politics or strategy. But all wars appear out of a clear blue sky, even to those who start them. And no strategy survives the first contact with the enemy. So all wars are a form of compulsory education for those foolish enough to think they have nothing to learn. And the three lesson that war teaches are always the same. The only sin in war is losing. The only assurance of losing is arrogance. And arrogance always leads to war.

"I bear a charmed life". Macbeth: Act V, scene viii

"I bear a charmed life". Macbeth: Act V, scene viii  “If you can look into the seeds of time, and say which grain will grow and which will not, speak” Macbeth; Act I, scene iii

“If you can look into the seeds of time, and say which grain will grow and which will not, speak” Macbeth; Act I, scene iii Forrest's return to America was greeted with packed houses and raves by most reviewers. There were some voices of dissent, such as William Winter, who wrote for the New York Tribune that Forrest behaved on stage like a maddened animal “bewildered by a grain of genius”. But such discontent was drowned out in the applause from Boston to Denver. American audiences liked their actors larger than life in those days, and Forrest was just about as large as he could get. In fact, everything would have been perfect but for two small details. First, Edwin could not resist sharing himself with every woman who swooned at his manly thighs (the vast numbers of whom Catherine had a little trouble dealing with), and second, Edwin decided to make a triumphal return tour of England in 1845.

Forrest's return to America was greeted with packed houses and raves by most reviewers. There were some voices of dissent, such as William Winter, who wrote for the New York Tribune that Forrest behaved on stage like a maddened animal “bewildered by a grain of genius”. But such discontent was drowned out in the applause from Boston to Denver. American audiences liked their actors larger than life in those days, and Forrest was just about as large as he could get. In fact, everything would have been perfect but for two small details. First, Edwin could not resist sharing himself with every woman who swooned at his manly thighs (the vast numbers of whom Catherine had a little trouble dealing with), and second, Edwin decided to make a triumphal return tour of England in 1845. "Fair is foul, and foul is fair". Macbeth: Act I, scene i.

"Fair is foul, and foul is fair". Macbeth: Act I, scene i. "What 's done is done" Macbeth: Act III, scene ii

"What 's done is done" Macbeth: Act III, scene ii “Let not light see my black and deep desires” Macbeth; Act I scene iv

“Let not light see my black and deep desires” Macbeth; Act I scene iv

“If chance will have me king, why, chance may crown me.” Macbeth; Act I, scene iii

“If chance will have me king, why, chance may crown me.” Macbeth; Act I, scene iii “Is this a dagger which I see before me?” Macbeth; Act II, scene i

“Is this a dagger which I see before me?” Macbeth; Act II, scene i "All the perfumes of Arabia will not sweeten this little hand.” Macbeth Act V, Scene i.

"All the perfumes of Arabia will not sweeten this little hand.” Macbeth Act V, Scene i.