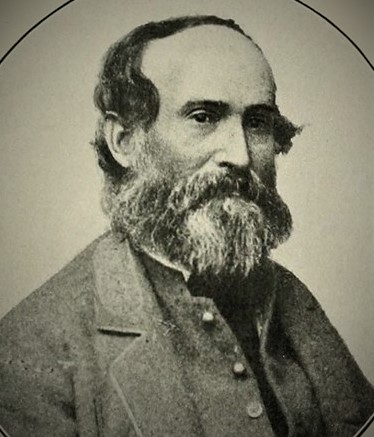

I believe that 47 year old Lieutenant General Richard Stoddert Ewell (above) was the "reigning eccentric" in the Army of Northern Virginia. He was courageous under fire and generous to a fault, an insomniac and a hypochondriac. At times his enormous bomb-shaped bald head seemed too heavy for his neck, and when he was tired it tipped toward one shoulder or the other.

When excited, profanity poured from his 5'8" frame in a shrill high voice. And Ewell (above) was prone to interrupting himself with quiet, unrelated interjections, like, "Now why do you suppose President Davis made me a Major General, anyway?", and "What would my grandfather think of that?" In comparison to his other traits, Ewell's pronounced lisp seemed mundane.

He had finally married in May, just before leaving on this campaign, to the woman who had nursed him after losing his left leg at Battle of Second Bull Run. His new bride was his first love and his first cousin, the iron willed and wealthy widow, Lizinka Campbell Brown. His personal aide was Lizinka's eldest son, and now "Baldy" Ewell's stepson, Major Campbell Brown (above). And on this crucial Wednesday, Major Brown spent most of the day carrying messages between Ewell and his stepfather's boss, General General Robert Edward Lee.

Just after 1:00 p.m. Major Brown had found General Lee atop Herr's Ridge. He informed Lee of Ewell's arrival on the battlefield, at the head of General Rodes' division. According to the Major, Lee was unhappy to find Archer and Davis' Brigades of Heth's division attacking McPherson's Ridge. When the rebels were thrown back, General Heth asked if Rode's division would join the assault. Lee replied, "No, I am not prepared to bring on a general engagement today. Longstreet is not (yet) up."

Five hours after the great battle had begun and Lee was still hoping to avoid a big fight. Lee now turned to the newly arrived Major Brown, seeking good news, asking "...with a peculiar searching...querulous impatience... whether General Ewell had heard anything of General Stuart." Brown noted "This from a man of Lee's habitual reserve, surprised me." Added Major Brown, Lee "impressed upon me, very strongly, that a general engagement was to be avoided until the rest of the army had arrived."

It took Brown over an hour to find Ewell again. "Old Baldy" was now atop Oak Hill and was staring down upon the Dutchmen of Howard's XI Corps on Oak Ridge. Ewell wrote later, he felt, "It was too late to avoid an engagement without abandoning the position already taken up.” Brown warned his stepfather that Lee was "seething with anger". But Ewell launched Rodes' 9,000 man division at the XI Corps. Again the first rebel assault was thrown back, but when Early's division arrived, Ewell also threw its 5,000 men at Barlow's Knoll, seeking to outflank Oak Hill.

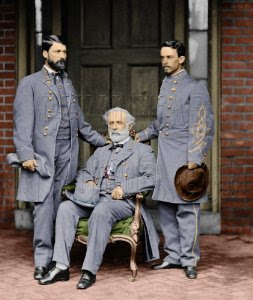

Finally, about one o'clock Lee (above) was forced to acknowledge reality and order all units to attack, - not so much order as a release of his commanders to continue their disobedience. Earlier, Lee had explained his philosophy of command to Captain Justus Scheibert, a Prussian observer with the army. "I plan and work with all my might to bring my troops to the right place at the right time," Lee had said, "(and) with that I have done my duty. As soon as I order the troops forward into battle, I lay the fate of my army in the hands of God.” And the divine's repeat of the Chancellorsville flanking attack encouraged Lee to accept his subordinate's disobedience.

By 5:00 p.m., as Lieutenant General Ewell was following his troops into the town of Gettysburg, the positive side of Lee's command style was on full display. The day had already been the 23rd largest battle of the American Civil War. Lee's 27,000 soldiers in 4 divisions had swept 22,000 Federal troops in 2 corps off the ridges west and north of Gettysburg. Confederate casualties numbered about 6,000, while the Federal forces had lost almost 9,000 dead,, wounded and missing. After Gettysburg, neither the I or XI Union Corps would appear on another battlefield. But after 5:00 p.m. the reverse side of Lee's command style made itself known.

It was now that Lee's aide, 25 year old Major Walter Herron Taylor (above), arrived with new orders for General Ewell. As was usual with Lee, they were verbal. And because they were, exactly what they were depends on who heard what was said.

Major Taylor (above, right) remembered Lee (above, center) issuing the following orders - "The enemy is retreating over those hills in great confusion. You only need press those people to secure possession of the heights. Do this, if possible." Having delivered the order, Taylor returned to the newly captured Seminary Ridge, on the opposite flank.

Lieutenant General Ewell, his staff and his brigade commanders, Major Generals Rodes and Early, rode a mile out the Hanover Road to where it crossed the rise called Benner's Hill, to get a close look at towering Culps Hill. A mile across the fields they saw troops moving at the base Culps Hill and assumed they were Federal infantry.

At about the same moment, in the new center of the Federal line atop Cemetery Hill, General Winfield Scott Hancock (above) was sitting on a stone wall with General Carl Schurz, watching the rebels struggling to adsorb their gains and lick their substantial wounds. Most of the Federal troops on the hill had been badly mauled, and were exhausted.

But they were still determined to fight, and with 85 cannon backing his men as they dug in, Hancock told Shurz he could hold the position until reinforcements arrived. And in a report at 5:25 p.m. Hancock told General Meade, "We have now taken position in the cemetery and cannot well be taken." But Hancock was facing west and north. And a mile directly behind and above him was Culp's Hill.

Standing atop Benner's Hill, Ewell, Early and Rodes contemplated the situation. All three saw Federal infantry on Culp's Hill (above).

Behind them, in the town of Gettysburg, their own units were intermingled and scattered. Rodes' division had suffered heavy causalities, as had Early's division - just how many dead and wounded could not be estimated until the units could be reformed, and a quick head count made. Many of the soldiers who were able to fight were tied up guarding the thousands of Federal prisoners just taken.

The only Division in Ewell's III Corps not yet bled in this fight were the 6,000 men under 47 year old Major General Edward "Allegheny" Johnson (above). Johnson's division had not quite reached Carlisle on 29 June, when Lee's orders to immediately concentrate the army at Chambersburg, arrived. The logical route was to turn Johnson's men around and march them back the way they had come - 30 miles south on the Cumberland Valley Pike. Logically General Rode's division, then at Mechanicsville, returned via Carlisle where they turned south, expecting to meet General Early's division at Gettysburg.

Then Lee shifted the concentration point to Cashtown. The change meant his army would be protected by the wall of South Mountain. And it also meant that as he approached from the north General Rodes would turn off the Carlisle Road and follow secondary roads toward Mummitsburg. By luck on the afternoon of 1 July this delivered Rodes on the flank of Heth's division as it attacked the ridges west of Gettysburg. But it also meant that Johnson's division, reaching the Cashtown Gap turn off from the Cumberland Valley Pike, now needed the same road as Lieutenant General A.P. Hill's supply trains, and Longstreet's I Corps. Inserting Johnson's men into the columns delayed both Johnston and Longstreet in reaching Gettysburg.

As Ewell, Early and Rodes were planning their assault on Culp's Hill, and awaiting Johnston they were interrupted by the arrival of Lieutenant Frederick Waugh Smith, son of 65 year old Brigadier General William "Extra Billy" Smith (above). Being the oldest general on the battlefield, and an ex-and the next (governor elect) of Virginia, "Extra Billy" carried an authority greater than either his rank or his talents deserved. Before the campaign, Early had asked General John Gordon to keep a close eye on the politician turned soldier turned politician. After entering Gettysburg, Gordon had sent Smith's 800 men 2 miles out the Hanover Pike as a flank guard. But Smith seemed unable to detach himself from the drama of the battle.

"Freddy" Smith (above) was the second messenger dispatched from his father. The first had warned General Early of Federal troops approaching down the Baltimore Pike.

But now the "overly excited" Freddy announced a large Federal force was forming up on the Baltimore Pike for an attack large enough to overwhelm Smith's small brigade along the Hanover Pike. Nobody on Benner's Hill except "Freddy Smith" believed there was a large Federal force on the Baltimore Pike. But General Early told his boss, "I...prefer to suspend my movements until I can send and inquire into it.’ When Ewell agreed, Early sent a second brigade to reinforce Smith, and get him under control.

That left Ewell with only Rodes' exhausted division to work with - not enough to take Culp's Hill against Federal infantry. So "Baldy" Ewell dispatched Captain James Powers Smith (above) - no relation to the governor - to General Lee, asking for reinforcements from A.P. Hill's Corps to make the assault. While waiting for the reply, Major General Johnson's arrived on the field after their second 25 mile march in 2 days.

It was after 6:00 p.m. before Johnson's men finally stumbled into positions facing Cemetery Hill and received orders to assault Cemetery Hill "...if he thought it possible". Johnson took a look at his weary men and stared 70 feet up the slope at the rows of Federal artillery staring back down at him and decided it was not possible.

Just about the moment that Johnson was reaching his decision, Captain Smith returned from General Lee. with bad news. A.P. Hill had no fresh troops available, in large part because Johnson's march had delayed the rest of A.P. Hill's Corps. There would be no reinforcements for an assault on Culp's Hill. But, added Lee, Ewell should go ahead with the attack "if practicable.” Again there were no written orders, and again the verbal ones carried a modifying phrase which weakened them. But Lee then went further, repeating his original written order, without a modifying phrase. Ewell was not to bring on a general engagement until the rest of the army - meaning Longstreet's Corps - had arrived.

With Early's division chasing shadows in the deepening dusk, and now out of position to attack Culp's Hill, Ewell decided to let his victorious men rest. Tomorrow there would be time to clear the Federals off Cemetery Hill and ridge. Except...

The infantry Federal Ewell, Early and Rodes had seen at 5:30 p.m. at the base of Culp's Hill were a Massachusetts brigade under General Thomas Ruger (above) from the Federal XII Corps, just arriving on the battle field.

And shortly thereafter Ruger received orders to withdraw for the night and encamp along the Baltimore Pike. These were the men "Extra Billy" Smith had seen gathering in the distance. But by 6:30 p.m., when Early's assault would have been launched, there were no Federal troops on the high ground overlooking Cemetery Hill and Ridge. And the chance to capture an unoccupied Culp's Hill became just another opportunity lost.

- 30 -