I keep looking at her face, and

honestly, I just don't see whatever it was that captured his heart.

They had the ultimate Age of Enlightenment cute-meet, but where he

was a 38 year old endlessly curious bon vivant sociable genius, a

doctor, a scientist and a poet, she had few friends and her only

interest was religion. Her father, Anthony Kingscote, must have

thought that at 27 his eldest daughter had long ago missed her chance

to find a husband. And Catherine's plain face and down turned mouth (above) hints that she had come to same conclusion. And then on a fair

September afternoon, his balloon landed in a meadow near her home,

and two years later she married one of the greatest men – ever -

the man responsible for saving hundreds of millions of lives by

applying the scientific method to an obvious problem. Clearly

Catherine must have had a secret appeal. And Edward Jenner was smart

enough to recognize it. Well, they also say opposites attract.

Edward Jenner had a few advantages. He

was born wealthy, but not so rich he didn't have to work for a

living, just rich enough he never cared more about money than about

people. He never patented his great discovery, because he didn't want

to add his profit to the cost of saving lives. And maybe that was

Catherine's influence. And maybe it was the humanity he'd always had.

And maybe it was because when he was still a child, his own father

had inoculated him against small pox.

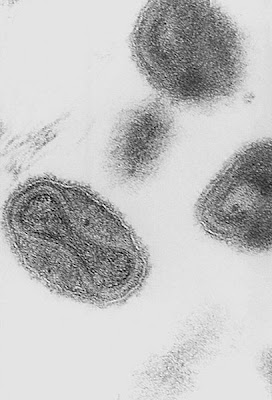

The two most deadly diseases in the

18th century were the Great Pox (syphilis) and the Small

Pox (Variola – Latin for spotted). Reading the genetic code of

Variola hints it evolved within the last 50,000 years from a virus

that infected rats and mice, and then moved on to horses and finally

people. It disfigured almost all of its human victims, leaving their

features scared and pockmarked, even blinding some survivors. It

killed half a million people every year – and 80% of the children

who were afflicted. The chink in Variola's protein armor was that it

had evolved into two strains, one which preferred temperatures of

around 99 degrees Fahrenheit before it stated dividing, and the

second which preferred something closer to 103 degrees.

They called the lesser of these two

evils the cow pox, and sometimes the udder pox, because that was

where the blisters often showed up on infected milk cows. And it was

the young women whose job it was to milk the cows who were the only

humans who usually contracted the cow pox. They would suffer a fever,

and feel weak and listless for a day or two, and, in sever cases have

ulcers break out on their hands an arms. But recovery was usually

rapid and complete, and there was an old wife's tale that having once

contracted cow pox, the women would then never suffer the greater

evil of smallpox. It was mucus from a cow pox ulcer which Richard's

father had applied to his son's open flesh, in the belief it would

somehow protect him from smallpox.

The working theory behind this idea was

first enunciated by the second century B.C. Greek doctor,

Hippocrates. Its most succinct version was “Like cures like.”

Bitten by a rapid dog? Drink a tea made from the hair of the dog that

bit you, or pack the fur into a poultice pressed against the wound.

The fifteenth century C.E. Englishman, Samuel Pepys, was advised to

follow this theory by drinking wine to cure a hangover. “I thought

(it) strange,” he wrote in his diary, “but I think find it true.”

And in 1765 London Doctor John Fewster published a paper entitled

“Cow pox and its ability to prevent smallpox.” But he was just

repeating the old wife's tale, and offered no proof. So the idea was

out there. It only waited for someone smart enough to put the obvious

to a scientific test.

In early May of 1796, Sarah Nelms a

regular patient of Edwards, and “a dairymaid at a farmer's near

this place”, came in with several lesions on her hand and arm. She

admitted cutting her finger on a thorn a few weeks previous, just

before milking Blossom, her master's cow. Upon examining both Sarah

and Blossom Edward diagnosed them both as suffering from the cow

pox. And he now approached his gardener, Mr. Phipps, offering to

inoculate ( from the Latin inoculare, meaning “to graft") his 8 year

old son James, against small pox. The gardener agreed, and on May

14th Edward cut into the healthy boy's arm, and then

inserted into the cut some pus taken directly from a sore on Sarah

Nelm's arm.

Within a few days James suffered a

slight fever. Nine days later he had a chill and lost his appetite,

but he quickly recovered. Then, 48 days after the first inoculation,

in July, Edward made new slices on both of James' arms, and inserted

scrapings taken directly from the pustules of a smallpox victim. And

this time what should have killed him did not even give the child a

fever. Nor did he infect his two older brothers, who shared his bed.

Over the next 20 years James Phipps would have pus from a small pox

victims inserted under his skin twenty separate times. And not once

did he ever contract the disease. He married and had two children.

And when Edward Jenner died, James was a mourner at his funeral. The

original boy who lived did not pass away until 1853, at the age of

65.

Edward Jenner coined the word vaccine

for his discovery, from the Latin 'vacca' for cow, as a tribute to

poor Blossom, whose horns and hide ended up hanging on the wall of

London's St George's medical school library. And that was the whole

story, but, of course it wasn't, because it wasn't that simple,

because nothing is that simple - certainly not the immune response

system developed on this planet over the last four billion years.

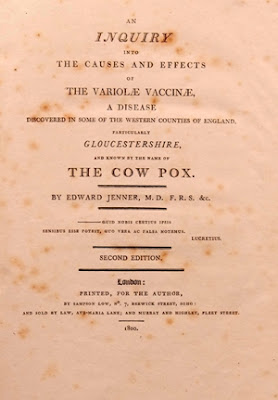

Edward duplicated his procedure with

nine more patients, including his own 11 year old son, and then wrote

it all up for the Royal Society of London for Improving Natural

Knowledge. And those geniuses rejected it. They refused to publish it

because they thought his idea was too revolutionary, and still lacked

proof. So Edward, convinced he was on the right track, redoubled his

efforts. When he had 23 cases and the Society still refused to

publicize his work, Edward self published, in a 1798 pamphlet

entitled “An Inquiry Into the Causes and Effects of the Variolæ

Vaccinæ, Or Cow-Pox”

By 1800, Edward Jenner's work had been

translated and published world-wide. Problems were revealed

There was a small percentage of

patients who had an allergic reaction at the vaccination sites, and

eventually it would be decided not to inoculate children, as their

immune systems were not yet strong enough to resist the cow pox. And

without a fuller understanding of how the human immune system

functioned, it was impossible to know “to a medical certainty”

(to use legal jargon) how the vaccine would affect specific groups of

patients. Still, the over all reaction was so positive that Edward

was surprised by the reaction of the people he called the

“anti-vaks”.

Opposition became centered on the

Medical Observer, a supplemental publication by the daily newspaper,

The Guardian. After 1807, and under editor Lewis Doxat, it condemned

Jenner's introduction of a “bestial humour into the human frame”,

and in 1808 its readers were assured they should not presume “When

the mischievous consequences of his vaccinating project shall have

descended to posterity...Jenner shall be despised.” Edward was even

accused of spreading Small pox, for various evil reasons. The

argument presented from the pulpit was that disease was the way God

punished sin, and any interference by vaccination was “diabolical”.

Under this barrage the percentage of vaccinated children and adults

in England still climbed up to around 76%. But without 100%

protection the Variola survived, and in January of 1902 there was

yet another outbreak in England that killed more than 2,000.

About 500 million human beings world

wide died of Smallpox after Edward Jenner introduced his vaccine. But

the last victim was Rahima Banu, a 2 year old girl in Bangladesh, in

1975. At 18 she married a farmer named Begum, and they gave birth to

four children (her again, below). And each of her children is living proof that while

religion may save souls, science saves lives.

The scientists working for the World

Health Organization issued a report on December 9, 1979, which

announced, “...the world and its people have won freedom from

Smallpox.” Variola was extinct, wiped out to the last living cell,

by the dedication of scientists and those working under their

guidance. It was, as Jenner himself wrote after the first successful

eradication on Caribbean islands, “I don’t imagine the annals of

history furnish an example of philanthropy so noble, so extensive as

this.”

His dear Catherine died of

Tuberculosis in 1815, and Edward followed her in January of 1823.

And for his life – and her's – we all owe a great debt. He

was like the bird in his poem “Address to a Robin”: “And when

rude winter comes and shows, His icicles and shivering snows, Hop

o'er my cheering hearth and be, One of my peaceful family: Then

Soothe me with thy plaintive song, Thou sweetest of the feather'd throng!”

- 30-

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please share your reaction.