I find it fascinating how we can easily forget things that were once common place. Consider this fable; in the final hours of Saturday, 20 May, 1995, Mrs. Paula Dixon leaped on the back seat of a motorbike, rushing to make a plane – British Airways flight 32, bound for London. Trying to stretch out her ten day vacation in Hong Kong, the 38 year old divorcee had left herself precious little time to make her 11:45 pm flight out of Kai Tak airport.

During her dash to make that plane, Paula fell off the moving bike, hitting the pavement and bruising and cutting her arm. After scrapping her self off, and finishing the trip, Paula made it to the departure gate with just moments to spare.

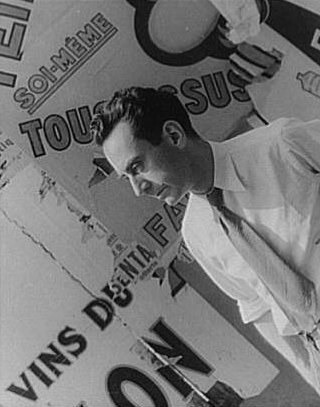

But while the 747 was waiting on the tarmac Paula Dixon's (above) arm began to hurt and swell. So she notified a flight attendant, who luckily was a trained nurse. And thus began a swirl of currents in which the fate of this mother of two would be swept between an obsessed turn-of-the-century factory worker, and a Dadaist acolyte born in South Philadelphia in the summer of 1890.

As the eldest of four children, Emmanuel Radnitzky grew up surrounded by threads and swaths and shreds of things. He was the first child of Russian immigrants, his father a garment factory worker who earned extra money by doing a little tailoring and his mother with an artistic flair who assembled collages out of errant scraps of clothing. When he was seven the family moved to the slums of the Williamsburg section of Brooklyn, New York City. And at about the same time, suffering the insults of anti-antisemitism the family shortened their name from Radnitzky to Ray. Emmanuel would soon shorten his first name to simply Man. So he became Man Ray.

The flight attendant asked if there was a a doctor among the passengers , and two responded - Professor of Surgery Angus Wallace and Doctor Tom Wong. Together they decided Paula had broken her arm, and at her urging, fashioned a quick fix - a splint out of a Hong Kong newspaper, and rubber bands. She was given morphine from the aircraft's first aid kit, and tried to relax while the plane took off, bound for Heathrow airport, 14 hours away.

But just an hour later, at 33,000 feet above the Bay of Bengal, Paula bent over to take off her shoes and felt a stabbing pain in her left side. Suddenly she couldn't catch her breath. One look convinced both doctors Paula had not only broken her arm, but a rib as well. And, when she bent over that broken rib had punctured the tissue surrounding her left lung, suddenly inflating it like a child's balloon and thus preventing her lung inside that tissue from expanding. Without immediate surgery, Paula Dixon was going to strangle to death.

Seventy miles east of Detroit, the town of Jackson, Michigan grew because people who thought they were going somewhere else, paused here for whatever reason, and stayed for whatever reason. The railroads came because the soil was good for farming, and since it was a convenient place to change crews, they built railroad shops here, which attracted other industry.

By 1900 the town of 25,000 included a mechanically inclined Canadian tinkerer named Albert J. Parkerhouse (above). He found work at the Timberlake Wire and Novelty Company, pulling cold brass and copper through dies to form lampshade frames, bed springs, paper clips, wheel spokes and wire fences, anything that could be sold for a profit.

Albert stayed because the work was steady and because if any of the workers stumbled upon an idea, the owner, John B. Timberlake, encouraged them to follow it. And one cold morning in 1903, Albert Parkerhouse was irritated because when he got to work there were no empty hooks to hang his heavy jacket from.

With Paula stretched out across an entire row of seats, and the improvised instruments sterilized with five star Courvoisier brandy, an incision was made just below her collar bone. Then while one doctor held the cut open with a knife and fork, the other took a catheter from the first aid kit. One end, with a flap in it, was slipped into a bottle of seltzer water - the flap keeping the fluid from rising into the tube. And then the open end of the catheter, stiffened at the suggestion of a flight attendant with a straightened wire coat hanger, was slowly forced through the muscle tissue and into Paula's chest cavity. The patient, Paula, who had no more anesthetic, said she felt like beef on butcher's hook.

In 1913 the young Man Ray was exposed to the electrifying Armory Show, which Teddy Roosevelt walked out of, declaring “This is not art!” But Man Ray thought it was, and he was, he said, "elevated" by it.

At the show he met the cubist painter of “Nude Descending a Staircase”(above), Marcel Duchamp. The two became fast friends, and enthusiasts of the heady freedom of "the Dada" movement. The word meant various things in various languages, but to German writer Hugo Ball who adopted it, it meant nonsense, the rejection of art as only things worthy of inclusion in a museum. In 1915 Man Ray had his first one man show in New York and bought a camera to document his art. Eventually he became best known for his surrealistic and absurdist photographs. But he never let go of the wonder and whimsy he had learned from mother, and what he now called his “ready-mades”.

Once the catheter had penetrated the tissue surrounding Paula's left lung, the coat hanger was removed, and the air pressing around Paula's lung could now escape into the catheter. Each time she expanded her lung, a little more of the air strangling her was expelled. The flap in the catheter and the seltzer water kept what was expelled from slipping back, and each breath got easier. Within ten minutes Paula Dixon was breathing normally. With a doctor at her side, the exhausted patient fell asleep. The exhausted doctors drank the remaining Courvoisier.

On and off for weeks, Albert Parkerhouse twisted and bent various lengths and thicknesses of wire from the factory floor. Finally he hit upon what he thought was the best design to support his jacket without wrinkling it. Timberlake filed a drawing of that twisted wire for a patent in January of 1904 (Number 822,981) (above) and made profits for the next 77 years pulling wire coat hangers.

Albert Parkerhouse (above) was not bitter he had received no share of the profits from his invention, but he was annoyed that on the patient application he was not listed as the inventor. A few years later he moved to Los Angeles where he started his own wire company. He died in 1927 of a ruptured ulcer at the age of 48.

The big white British Airways 747 landed at London's Heathrow airport at 5:00 in the morning of Sunday 21 May, 1995. Paula, who felt good enough that she had eaten breakfast, was immediately transported to Hillington Hospital, just north of the airport . Here her make-shift surgery was closed and she slowly recovered from the ordeal, One year later she returned to Hong Kong to be married to her motor biking driver, German banker Thomas Galster. She told reporters, “If it wasn’t for my doctors I wouldn't be here today”. And, she might have added, she also owed her life to a wire coat hanger. If one had not been invented by an irritated Albert Parkerhouse in 1903, Paula Dixon would have died on that plane in 1995. That is what you call an unintended consequence.

Man Ray was finding it difficult to make a living as an artist in New York City. He wrote, “All New York is Dada, and will not tolerate a rival.” In July of 1921 he burned many of his older, unsold works, borrowed $500, and set off for Paris, where he would live the rest of his life.

One of his last works created in New York City was “Obstruction”, a three dimensional collage, described by the N.Y. Museum of Modern Art as a “pyramid of coat-hangers, each with two more hangers suspended from its ends...in arithmetic progression until almost an entire room was obstructed. This pyramid had an even, but changeable equilibrium; if only one hanger was set in motion, the entire pyramid oscillated with it.”

It must have reminded Emmanuel of his childhood, surrounded by a forest of hangers, all suspended just out of reach, representing a whimsical playground for the child and a crushing existence of endless work for his parents, the pattern of their collective and individual lives, connected yet separate, each suspended from the others. Life, Emmanuel seemed to be saying, is mostly just hanging on.

- 30 -

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)