I offer proof there is no such thing as

useless information, as illustrated by the fate of the 600 elite

German paratroopers who floated down or thudded into rough glider

landings on the dirt air field of Maleme in Western Crete, at about

eight on the morning of May 20th, 1941. Six short hours later 400 of

them were dead, killed by poorly armed, badly disorganized and

under strength New Zealand infantry. And what largely killed those

confident well trained, well armed Teutonic warriors was information

uncovered forty years earlier and sixty miles to the east, written

4,000 years before men could fly.

The second imperial palace built at

Knossos on bronze age Crete was so large visitors got lost in its

labyrinthine corridors. It had been built for King Minos, and was

occupied for over 400 years. It had hot showers, and flush toilets,

and gardens. Its walls were adorned with colorful frescoes of sacred

bulls, graceful women, and brave men. Its gold came 300 miles from

Egypt, its olive oil 100 miles from Greece, its ceder throne, 400

miles from Lebanon. And then about 1375 B.C., this kingdom simply

disappeared. Time eventually even wiped out its memory. For most of

human history, people had no idea the acrobats of Crete were

cartwheeling over the horns of bulls before Moses challenged Pharaoh.

Then a British archaeologist went looking for a new meaning in his

life.

Little Arthur Evans (above) - he stood just five

feet two inches tall - had always been fascinated with ancient

history, but only ancient history. He almost failed his final exams

at Oxford because he knew nothing that had happened after Richard the

Lion Heart died, in 1199 A.D. Evans spent half his life as a

dilettante archaeologist, digging about the edges of the crumbling

Ottoman Empire. When his wife Margaret died in the spring of 1893,

the heartbroken 43 year old Evans went digging with a new purpose. He

used his inheritance to buy land already identified as a palace three

miles south of the port of Heraklion on Crete.

Beginning in the year 1900, Evans

spent six years unearthing the great palace at Knossos. Its murals

were so exuberant, its architecture so confident, its wealth so

obvious, that Evans was certain it had been the center of a great

empire which rose and fell while the ancient Greeks were still

barbarians. The record of its achievements and soul were right at

hand, in the thousand or so clay tablets scattered about the palace.

But they were written in what seemed to be two unknown languages,

younger by a millennium than the cuneiform tablets of Sumer and

Babylon, but older by a century than the oldest Egyptian hieroglyphs.

Evans labeled the languages Linear A

and B. His obvious choice was to attack Linear B (above) first, since the

majority of the tablets were in that language. But the best brains in

England were unable to read the words. After more than a decade of

study the only thing Evans was certain of, was that it was not

Greek. After World War One more tablets with the same mysterious

pictographic language were unearthed in the palaces at Pylos,

Thebes, Corinth and Mycenae, on mainland Greece As the number of

uncovered tablet shards approached 3,000, the best brains in the world

were still unable to read them. How could you decipher an unknown

language, once the authors and speakers, and everyone who ever read

or spoke the language, was long dead?

For 1,500 years the most popular method

to decipher coded messages was the one invented by the Syrian

mathematician Al-Kindi - frequency analysis. In essence, he reduced

the language to a math problem, figuring the most common letter used

in each word, (in English it is, “e”) and working back from

there. But none of the symbols used in Linear B appeared in any

statistically significant variation. The diligent mathematicians

Evan's hired simply did not have the resources to crack the puzzle of

Linear B. But the effort did provide a good testing ground for new

theories, just in time to deal with an ambitious electrical engineer

who thought he had a great way to get rich.

His name was Arthur Scherbius, and in

1918 he marketed his new mechanical rotor device under the name

“Enigma”. Pushing the letter “e” on Scherbius's keyboard

turned a mechanical rotor (above) one spot forward. There were twenty-six

spots on each rotor, so the letter produced by the rotor would be a

different, totally random letter from the one input, determined only by

the original position of that rotor. Putting the rotors in sequence

would make the code practically impossible to break, unless you knew

the starting setting of each rotor. And those could be changed either

randomly or according to a schedule. In 1926 Scherbius sold his

machine to the German Navy, and the following year to the German

Army, who thought the code was unbreakable.

And it might have been, but in 1928 a

minor bureaucrat on the Army General Staff did something

stupid. Instead of sending their new Enigma machine (above) to their embassy

in Warsaw, Poland in a diplomatic pouch, he sent it by mail. When it

failed to promptly arrive, the ranking German officer in Warsaw

panicked, and asked the Poles to please look for the package.

Intrigued, the Polish postal workers searched for, found and opened the box,

and got their first look at the Enigma machine. Polish intelligence service spent a long

weekend disassembling it and building a duplicate machine. Then they

carefully repackaged the original and delivered it to the relived

German embassy staff.

The Germans had little reason to worry

even if they had known. With eight rotors wired in sequence,

Scherbius had figured it would take 1,000 technicians using frequency

analysis, 900 million years to try every possible combination of keys

and rotor settings just to read a single message. And he was right.

The Polish code breakers struggled with the machine for a decade, but

came up with nothing. Finally in 1939, facing an impending German

invasion, the Poles shared their duplicate Enigma with British

Intelligence. And in 1941, a brilliant English mathematician named

Arthur Turing, built his own electro-mechanical machine (above) which could

try each of the millions of possible mechanical rotor settings on

Enigma in a matter of hours. With that, it became possible to break

the unbreakable German codes.

The first use of this British “Ultra

Secret” was on April 28th, 1941, when their commander

on Crete was given details of the coming German invasion. General

Freyberg was not sure he could completely trust this new source, and

divided his troops between the sea coast and the air bases, where Ultra said the attack would come.

But

enough men were guarding Maleme airfield on May 20th 1941

to slaughter the German units as they landed. British Prime Minster

Winston Churchill pointed out that “"At no moment in the war

was our intelligence so truly and precisely informed.”

In the end

it did not save Crete, because the German air force prevented General

Freyberg from bringing his reinforcements back from the coast.

Eventually German reinforcements swamped the New Zealanders and forced the

British to evacuate the island.. The battle cost the British 3,990

dead and 17,000 captured. But it cost the Germans 6,698 dead, and 370

aircraft destroyed. Their decimated parachute battalions never made

another massive combat drop.

A little over two months before the fall of

Crete, little Arthur Evans (above) died in England, still convinced that

Linear B was an as yet unknown language. And through the multiplying

effect of tenure and graduate students, he was able to reach out from beyond the grave to influence the effort to decode his tablets for another

generation. The solution, it turned out, had been offered by the 13th

century Franciscan monk and philosopher Roger Bacon, from his study

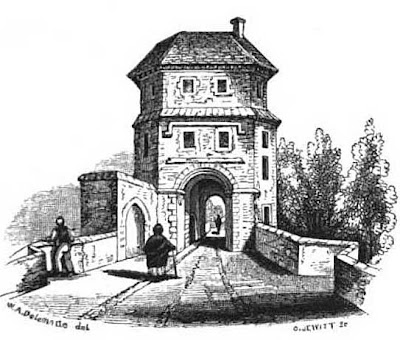

atop Folly Bridge (below). Bacon wrote, “Prudens quaestio dimidium scientiae”,

or “Half the answer is asking the right question.”

-30 -

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please share your reaction.