I can imagine what it was like to wake

up every morning as a slave. Can you? Each dawn mocked you with a

false promise of hope. Every evening, your future died again in darkness. Should your gaze fall upon your children you could not

help but wonder if this day they would be sold away, because “masa'”

lost a bet, or wanted to buy his child a present. Modern apologists

for slavery may want to believe beatings were uncommon. But we know

from personal letters by her master that for 30 years a woman named Betty was

Rachel Jackson's personal slave, and that in the General's words, she

“must be ruled with the cowhide” - meaning she was periodically

whipped. What kind of a woman was this white slave master, Rachel

Jackson, who could live every day with an intimate, and then coldly

countenance her being beating?

On November 3, 1813, militia under

General Andrew Jackson attacked the Creek Indian village of

Talulshatche, and in the words of participant David Crockett, “We

shot them down like dogs.” A child of eight months was found alive

in the burning village, and was delivered to the General, evidently

as a trophy. But the orphaned Jackson felt what he called “an

unusual sympathy” for the orphaned child. Andrew sent the baby to

his home, instructing Rachel, “I...want him well taken care of,

(as) he may have been given to me for some valuable purpose.”

He was given the name of Lyncoya and

raised in the main house at the Hermitage, along with Jackson's

nephew, Andrew Jackson, Jr. He was the closest thing to her own child

Rachel Jackson would ever have. At the age of five Lyncoya made

himself a bow and arrows, and in full war paint would descend,

issuing high pitched battle screams without warning on unwary

visitors. At eight he began attending a local school, but rebelled,

and ran away several times. His third year Lyncoya began to apply

himself, and showed an aptitude for mechanical devices. He also began

to spend much of his time alone. His academic improvements were so

great that General Jackson began to think about sending his adopted

son to West Point. But it was not to be.

It seems likely that after the

General's loss in the Presidential election of 1824, the boy was seen as a political liability: Perhaps. But for whatever reason Lyncoya Jackson never applied to the

military academy. Instead, in 1827, he became an indentured servant

to a saddle maker in Nashville, Tennessee. For a child with

understandable abandonment issues, his first time away from the only

security he knew must have been stressful. The next winter Lyconia

came down with a cold, which settled in his lungs. He told his

employer he wanted to “go home” to the Hermitage (above). That winter and

spring Rachel nursed him and was often seen with the 16 year old in

her carriage, seeing he got fresh air. But the boy died on June 17,

1827. He was buried somewhere on the grounds of the Hermitage, in an

unmarked grave. Perhaps his resting place would have been remembered

if his adoptive mother, Rachel, had lived.

On the morning of Wednesday, December

17th, Rachel Jackson (above) was overseeing the slaves packing up

her life for the move to Washington, when she suddenly issued a

“horrible shriek” and grabbed at her heart. A slave woman known

only as Old Hanna rushed to Rachel's side and found her struggling

for breath. Hanna lowered her mistress into a chair, and began to

desperately rub Rachel's side “till she was black and blue”. The

General was sent for, and he sent for the family doctor. For the

next three days and nights Andrew never left her side.

On the third day Rachel seemed to

recover, and she urged Andrew to go to bed and get some sleep. Five

minutes after he left her room, the slaves lifted Rachel up while they changed the sheets. And while sitting in a chair, in the

arms of Old Hanna, Rachel Jackson suffered another heart attack. She

issued a long, loud cry, followed by “a rattling in her throat”,

and died in the arms of a slave, December 22, 1828.

It is an insight into generations of

slave masters and mistress in the antebellum south, that their first

human touch in their life was usually the rough working hands of

slave women, and their last conscious touch with humanity was in the

exact same way. They had no control over that first contact. But they

did have control over the last.

Rachel was buried in the gown she had

made for the inaugural ball. And on her tombstone, Andrew had caved

the words, “A being so gentle and so virtuous slander might wound,

but could not dishonor.”

Even in the words on his wife's

memorial, Andrew Jackson managed to bury his own pain, beneath his

hatred for those he held responsible. Many historians have

suggested that Jackson's anger over Rachel's death changed the man. He wrote, “I

can and do forgive all my enemies. But those vile wretches who have

slandered her must look to God for mercy.” But Jackson was a hater

long before he ever met Rachel. He was even a hater before his mother

died while tending to others, rather than her own son. It almost

seems Andrew Jackson was born hating.

On March 4, 1829, Andrew Jackson became President. In a bit of stage drama, President. John Quincy Adams did not attend the

ceremony, as Jackson had refused to visit him in the White House,

despite having arrived in Washington days earlier. And so began the

Presidency of Andrew Jackson: angry. Henry Clay compared Jackson's

administration to a tornado, destroying everything in his path. Well,

not everything. When he left the White House eight years later,

Andrew Jackson said two things of real import. One was purely

personal, the other purely public. When asked if there was anything

he regretted about his time as President, he admitted to two, “That

I have not shot Henry Clay or hanged John C. Calhoun.”

But in his farewell address to the nation

in December of 1837, the original small government revolutionary,

warned the American public, “...unless you become more

watchful...and check this spirit of monopoly and thirst for exclusive

privileges, you will in the end find that the most important powers

of Government have been given...away, and the control over your

dearest interests has passed into the hands of these corporations.”

That remark proved that whatever his personal failings, Andrew

Jackson was ideologically a lot closer to Henry Clay than he would

have dared to admit.

And closer to Johnny Q, as well. Three

months after Jackson took the oath of office, at about one on the afternoon of June 8, 1829, in

Providence, Rhode Island, John Quincy Adam's 28 year old eldest son, the handsome George

Washington Adams (above), boarded the double wheeled steam ship, Benjamin

Franklin.

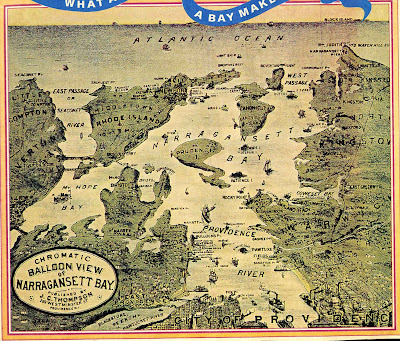

While Captain Eliuh S. Bunker guided the 144 foot long, 419

ton double deck packet boat down Narraganset Bay, the retired two

term Congressman remained in his cabin, complaining of illness. As

the sun set the Franklin slipped passed Block Island and entered Long

Island Sound. They missed George in the forward bar that night, as he

was a regular on every trip between the family home south of Boston, and New York City.

George did not leave his cabin until

just about two in the morning of June 9, and was seen walking on the

open deck wearing a hat and cloak. He was heard pacing for some little time, and then somewhere in the lonely dark, George

lost his way. At about four in the morning,his outer garments were

found lying on the deck. If he left a note of explanation, it was not

found. Four days later his corpse washed ashore on Long Island. To

compare the grief that now befell the John Quincy and Louisa Adams,

against that felt earlier by Andrew and Rachel Jackson is pointless, and yet to the point. One of the

things that binds all humans together is grief and its companion,

love. We dream of the one, knowing it never arrives alone. It is our commonality, our shared heritage, which, it seems, we spend a lifetime denying.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please share your reaction.