I

imagine the Florida and Mississippi boys – the called each other

“boys” - regretted mocking the New York engineers that Tuesday

afternoon, The stronger voiced had bellowed the 350 yards across the

Rappahannock River, urging the brawny union men to come rest in the

shade of the trees on their side of the river. But about 1:00 p.m.,

when 4 batteries of Federal artillery finally arrived and begun to

blast away, the laughter ceased. While rebel sharpshooters killed 6

sons of New York and wounded 18 more, the engineers persisted in

unloading 10 pontoon boats at the river's edge. Then 2 companies of

Vermont boys rushed to the river, and in broad daylight the engineers

paddled them across the open water to the Confederate shore.

By

now the Florida and Mississippi skirmishers had been reinforced, but

the granite state boys charged with the the bullets whistling over their

heads. As the engineers returned for more men, the 2 companies of

Union troops captured the Confederate rifle pits, and 6 officers

and 84 men. Surprisingly, the Vermont boys suffered just 7 wounded

in the head-on assault. The Army of the Potomac may have suffered

humiliating defeat in its last 2 encounters with the Army of Northern

Virginia, but on this day, 5 June, 1863, it displayed audacity and a

pugnacious spirit.

By evening there was a full brigade of Vermont

boys on the southern side of the river, and the New York engineers

were stringing the pontoon boats together to assemble 2 bridges at Fredrick's Crossing (above) above where Deep Run Creek (above, far right) joined the Rappannock River, just below

Fredricksburg, Virginia. But one of the Vermont

officer's whispered a note of discontent about the successful

operation, when he wondered, "Why they (the rebels) let

our men quietly entrench themselves when it lay within their power to

put them to a great deal of inconvenience, seemed strange at the

time.”

Six

months earlier, at the end of January 1863, President Abraham

Lincoln, had sent a very curious letter to the new commander of the

Army of the Potomac, Major General Joseph “Fighting Joe” Hooker.

Usually such notes after promotions are designed to inspire

confidence, but having suffered through 2 rounds of the arrogant

George McCellan – the Peninsula Campaign and Antietam - the

foolishness of General John Pope - Second Mananas – and the

blundering of Ambrose Burnside – Fredricksburg – Lincoln was

more sanguine about the Massachusetts General's abilities.

After

reminding Hooker he was responsible for guarding Washington, D.C. and Harpers

Ferry, Virginia, the President warned Hooker (above), “...I am not quite

satisfied with you. I believe you to be a brave and a skillful

soldier, which, of course, I like. I also believe you do not mix

politics with your profession, in which you are right...You have

confidence in yourself ..You are ambitious, which, within reasonable

bounds, does good rather than harm. But I think that during Gen.

Burnside's command... you have taken counsel of your ambition, and

thwarted him as much as you could, in which you did a great wrong to

the country...I have heard...of your recently saying that both the

Army and the Government needed a Dictator. Of course it was not for

this, but in spite of it, that I have given you the command. Only

those generals who gain successes, can set up dictators. What I now

ask of you is military success, and I will risk the dictatorship...”

Hooker had rewarded the president with the debacle of

Chancellorsville, 18,000 Federal casualties, and a retreat back

behind the Rappannock. “Fighting Joe” had not been relieved of

his command at once because he still displayed a talent for taking

care of his men. It was Hooker who had rebuilt the army after the

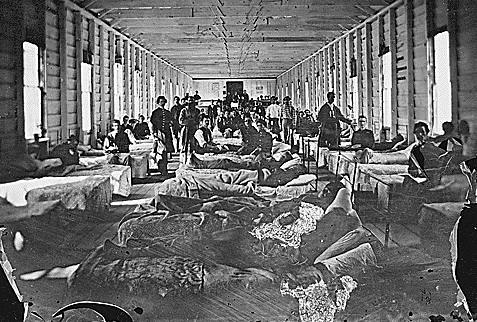

bloody failure at Fredricksburg, by improving the supply lines,

improving sanitary conditions in camp

And he formalized the system of 24

and 48 hour passes in all units, even those in Washington, D.C. - where the workers in the

legal houses of prostitution became known as “Hooker's Division” The new army was so improved that within a month of Chancellorsville,

it could display both elan and competency at Fredrick's Crossing, aka

Deep Run Creek. And it was Joe Hooker who had dreamed up the cross

river punch, and now he wanted to go further.

General Hooker (above) had not informed his superiors, General Henry Halleck and President

Lincoln, of his intention to cross the river until two hours before

launching the attack. He justified his aggressiveness with balloon

observations that several rebel camps on the west bank had

disappeared. If, as Hooker suspected, Lee was moving north,

Fighting Joe saw an opening.”I am of the opinion,” he telegraphed

Lincoln, “that it is my duty to pitch into his rear...” Hooker

suggested a “rapid advance on Richmond”, adding that the capture of

the rebel capital would be “the most speedy and certain mode of

giving the rebellion a mortal blow.”

Appalled,

Lincoln replied at 4:00 p.m. that same Tuesday, the Illinois lawyer

trying desperately to explain military reality to the West Point

graduate. “If he (Lee) should leave a rear force,” telegraphed

Lincoln, “it would fight in entrenchments and have you at (a) disadvantage” Lincoln then Americanized Napoleon's principles of

warfare, explaining an army fighting with the Rappahannock at its back

was “...like an ox jumped half over a fence and liable to be torn

by dogs front and rear, without a fair chance to gore one way or kick

the other. If Lee would come to my side of the river, I would keep on

the same side, and fight him...”

Forty minutes later Hooker's

military superior, General Halleck, asked “Would it not be more

advantageous to fight his movable column first, instead of first

attacking his entrenchments, with your own forces separated by the

Rappahannock?” Latter Halleck telegraphed that Lincoln had asked if

he agreed with the President's military assessment. Halleck assured

Hooker, “I do.”

And

that was that. Still, Hooker was still reluctant to lose his glorious coup

de main on Richmond, insisting on holding onto the bridgehead “for a few days”. But something else arose which

distracted the Massachusetts native.

Federal Brigadier General John Buford reported evidence that J.E.B. Stuart and his entire Rebel

cavalry corps, almost 7,000 troopers (above), had concentrated near Brandy Station in

Culpeper County, Virginia.. Given the strain such a gathering of

horses and men would place on the rebel supply train, it was obvious

General Stuart must be preparing another raid into Maryland.

And

Federal Major General Alfred Pleasonton (above) suggested he take 7,000 blue coated cavalry and 4,000 infantry south of the Rappahannock to break up the raid before

it started. On 7 June, 1863, General Hooker approved the operation, to “disperse

and destroy" the rebel cavalry.

What neither

Hooker nor Pleasanton, nor even John Buford, knew was that not only

were the rebel cavalry gathering in Culpeper county, but so were the

infantry corps of Generals Richard Ewell and "Old Pete" Longstreet - 54,000 men preparing for

the invasion of Pennsylvania. And the Federal cavalry was about to

poke their nose right into that hornet's nest.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please share your reaction.