I wonder what 38 year old Captain Thomas Benton Weir (above) expected to see a when he topped the twin promontory which bears his name? It was about 5:45pm on Saturday, 25 June, 1876. The Ohio Captain was one and a half miles in front of Reno Hill. And by advancing here, Weir was endangering the lives of the 30 or so men who followed him, plus the more than 300 men he had left vulnerable on Reno Hill. Why was he doing this? What the hell did he really expect to find?

Thomas Weir had been a member of the Custer "Royal Family" (above) since the Civil War, basking in reflected warmth from the "Son of the Morning Star". Libbie Custer enjoyed Weir's "quick mind and wit," calling him “well read, and social in his disposition”, and Weir had made a point of endearing himself to her. But eventually, as with the friend's of most addicts, a breaking point came. Libbie, who had converted "Audie" into a teetotaler, finally drew the line. In the fall of 1874, after Reno had reprimanded the captain for being intoxicated on duty, Custer would accept no further excuses. The Royal Family had disowned Thomas Weir.

On Sunday, 25 June, 1876, Captain Thomas Weir (above) was in command of "D" company, explicitly subordinated to Captain Benteen in his three company battalion sent to check the southern end of the Little Big Horn valley.

At 5:15pm, Captain Thomas McDougall, his escorts and the pack train had reached the defensive position on "Reno Hill". Major Marcus Reno now had 345 men - counting the 11 men the scout Gardner had just brought in from the valley fight. They had 24,000 rounds of ammunition, 12 days of hardtack and 2 days grain for the horses. What they did not have was water. But for the first time since noon, when Custer had divided his command, the majority of the seventh cavalry was in a position to defend themselves.

While the command was using carbine fire to suppress the Indians who were still clambering up the bluff, the officers gathered to discuss the tactical situation. Abruptly most of the Indians still in the valley mounted and rode northward. Remembered Benteen, “Heavy firing was heard down the river. During this time the questions were being asked: "What's the matter with Custer, that he don't send word? What we shall do?" "Wonder what we are staying here for?...but still no one seemed to show great anxiety, nor do I know that any one felt any serious apprehension but that Custer could and would take care of himself.”

It was now that Captain Weir approached Captain Benteen. According to a private who overheard the exchange, Weir insisted, "Custer must be around here somewhere and we ought to go to him." Benteen replied that because they were surrounded by armed hostiles the command should remain where it was. "Well, " replied Weir, "if no one else goes to Custer, I will go." Benteen said, "No, you cannot." Despite this, Weir returned to his position, mounted up and with only an orderly, rode off to the north.

Assuming Weir had received permission for the scout from Reno, his second in command, 30 year old Winfield Scott Edgerly (above) mounted "D" troop and followed toward the twin peaks of Weir Point, a mile and a half away.

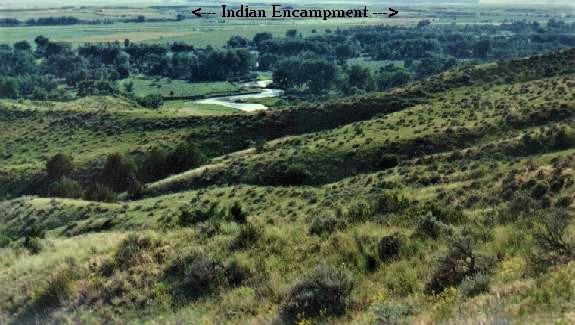

But having arrived there, Weir dismounted. To see, what? The clear dry western air put his visible horizon over the rolling sage brush and grasses at more than 3 miles. And he stood there for a few moments with just his orderly, holding his horse, gazing into the distance. To his right, up the slope, he could see two Indians moving to flank the advancing "D" troop. By hand signals he warned Lieutenant Edgerly, who threw out a skirmish line. But Weir still stood there, on Weir point staring into the distance. What held him there?

A few moments later two more soldiers rode up - 38 year old Sergeant James Flanagan and Private William Morrin, both of "M" troop. Eventually their arrival prompted Weir to point and announce, "That is Custer over there. " Whereupon he mounted his horse, as if to gallop to Custer's rescue.

He was stopped by Sergeant James Flanagan, who said, "Here, Captain, you had better take a look through the glasses; I think those are Indians." Weir had ridden out in search of Custer without a telescope or binoculars, making the endeavor even more of a hopeless pointless romantic act.

In fact, Flanagan had seen more than that. He might have witnessed the death of perhaps the last man to escape last stand hill. When he first raised the binoculars to his eye he had see a mile distant a trooper on horseback, being chased by Indian warriors, who cut the man off and killed him.

When Flanagan passed the binoculars to Weir, the captain saw across two to three miles of heat shimmers and mirages, according to the Sergeant, "...clouds of dust rising from the bluffs to the north where Custer and his men were wiped out." According to Flanagan, having gotten a good look through the magnifying glasses, and with Flanagan there to confirm what was visible , Weir changed his mind about leaving the place. Accordingly the men were dismounted and their horses were led behind the hill.”

The cranky Captain Fredrick Benteen, who would shortly join his rebellious officers, explained what little he could see from the same perspective. "The air was full of dust. We could see stationary groups of horsemen, and individual horsemen moving about. From their grouping and the manner in which they sat their horses we knew they were Indians. "

Lieutenant Edgerly had thrown "D" troop out in a skirmish line on the right or east wing from Weir Point, and within a few minutes the 42 year old Lieutenant Edward Settle Godfrey arrived and extended the skirmish line westward with his "K" troop. Next to him 33 year old Captain Thomas Henry French placed his "M" troop in the skirmish line. But they did not remain there for long. Benteen had come come not to support them but to bring them back to a better defensive position, closer to Reno's original hilltop.

A retreat was clearly called for. A trooper remembered the hills were covered with Sioux and Cheyenne warriors “...as thick as grasshoppers in a harvest field." Another soldier recalled fresh dust rising in all directions converging on Weir Point. Lieutenant French shouted the order to retreat to Edgerly. Both companies immediately mounted and began to ride to the rear. But Edgerly and his aide, Private Charles Sanders, hung back to get in a last shot or two. Then, just as Lieutenant Edgerly and his aide were preparing to run for it they discovered a wounded man crawling through the dry grass.

Edgerly recognized him as Private Vincent Charley (above), a 22 year old Swiss born red haired member of "D" troop. He had been shot through the hip, and hit his head when thrown from his horse. Charley begged the Lieutenant to take him with them. But Edgerly felt they did not have time to help, and told Charley to hide in ravine somewhere. As the two men galloped away they looked back and saw two Indians fall upon the defenseless trooper. Three days later Vincent Charley's body would be found with a stake driven into the back of his throat. And that was the cost of Thomas Weir's need to see what had become of Custer.

Lieutenant Godfrey's "M" troop provided skirmish line covering fire for the retreat, but Benteen quickly realized what Reno had learned some hours before - the skirmish line was easily out flanked and the gun fire not accurate enough to suppress direct the fire from repeating rifles and the indirect fire from bows and arrows.

The entire surviving portions of the 7th Cavalry occupied a new position, a shallow depression with a steep cliff to the west over looking the Little Big Horn River. Reno had the horses and mules gathered in the center, and stripped of their saddles and pack mounts, which the men used for barricades.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)