I might call Thutmose III a mummy’s boy. His official mother was his aunt, Hatshepsut (above), the second female Pharaoh (who we can be certain of). She had been the Great Royal God Wife of Thutmose II until he died in 1479 B.C. E. Thutmose III’s actual father was also Hatshepsut’s own half brother - Egyptian royal family trees tend to lean heavily on inbreeding.

Hatshepsut ran the two Kingdoms of Upper and Lower Egypt (above) for twenty years as Pharaoh, while Thutmose III remained the Pharaoh-in-waiting, since his actual birth mother, Iset, had been a "lesser" wife. And it seems likely Hatshepsut had been pretty distracted in her latter years.

Examination of her mummy (above) in the Cairo museum reveals that besides menopause (she was in her mid-fifties when she died) Hatshepsut suffered from arthritis, diabetes, liver and bone cancer, and really bad teeth. Of course most Egyptians had bad teeth, a by-product of chewing sand in every mouth full of food.

And what finally put Hatshepsut in her Luxor Temple, on 10 March, 1459 B.C., was blood poisoning caused by an abscess in her gums. And then, finally, after all those years playing second fiddle to his aunt, Thutmose, a powerful young man with a strong strain of Nubian blood in his veins, felt the need to reassert Egypt's authority on his northern border. And quickly.

Within days of ascending to the Throne of Horus, the 22 year old Thutmose III (above) ordered an army to gather troops and supplies by the last week of August 1458 B.C, at the border fortress of Tjaru in the Nile Delta.

The immediate threat facing Thutmose was the minor city state of Megiddo, which was flexing it's muscle. Now, this small city, 200 miles northeast of Tjaru, was not a real military threat to the great Egyptian empire. But the crises of Megiddo was a matter of tenderness.

The northwest border of Egypt was officially drawn where the coastal road crossed the Gaza Wadi. But beyond that usually dry stream bed were the hills which formed the east bank of the river Jordan. And in those bare and barren hills were the copper mines of southern Canaan.

See, stone age pottery kilns were just able to produce temperatures above 1,000 degrees Celsius, which could melt copper. And when naturally or artificially contaminated with tin or arsenic, copper made bronze. And bronze tools had many advantages over stone. They were lighter. They held a point and an edge longer. They are easier to shape, easier to sharpen, they are durable and should they break, they can be heated until they softened, and then reformed. Or, melted and cast as an entirely new tool.

The Bronze Age had begun about 1,000 years before Thutmose became Pharaoh, and although copper was a relatively rare metal, it was heavily mined along the southern end of the narrow strip of arable land which connects Africa to Eurasia, called the Levantine Corridor, Egypt had dominated the Levantine since about 1500 B.C.E., but had given up annexing the region because of resistance from the local Semitic population, called the Canaanites. It was the Canaanites who mined the copper and sold bronze to the Egyptians. But they also sold some bronze to the kingdom of Mittani, 350 miles north of Megiddo, at the northern end of the Levantine Corridor.

Mittani's (above) capital was along the Queiq river, was the city of Aleppo, one of the oldest continuously occupied cities in the world. And Mittani was on the rise, having recently defeated the ancient power of Babylon. King Barattarna of Mittani had made a treaty with Meggido as a tentative first challenge to the Egyptians. He supplied them with bronze chain mail and a few three man chariots. It seemed a low risk strategy as long as Hatshepsut was sick. After her death, Thutmose III decided to attend to these wayward Canaanites.

There was a delay in gathering the army, and Thutmose did not leave Tjaru until February of 1457 B.C. His Egyptian army was mostly infantry, perhaps 10,000 men, divided into platoons of six to ten men each, consisting of a mix of bowmen and lancers.

There was a delay in gathering the army, and Thutmose did not leave Tjaru until February of 1457 B.C. His Egyptian army was mostly infantry, perhaps 10,000 men, divided into platoons of six to ten men each, consisting of a mix of bowmen and lancers.

The smaller mobile force of two-horse chariots were not built for long distance travel, and on the march the chariots had to be light enough for each to be carried by their shield men. On this march across the Sinai (the Red Deseret) skirmishers advanced to the front while raiding parties ranged along the flanks, gathering sheep, goats grain and water for each night’s camp. Behind came the baggage train of ox carts carrying supplies, repair tents and blacksmiths, soothsayers, priests and musicians.

These people were used to walking, and never rode on horseback, so the army did not reach the Philistine fortress of Gaza (“The key to Syria”) until mid-March. After another 11 days marching up the coastal plain Thutmose’s army entered the port of Jamnia, near present day Tel Aviv. Here they rested while scouts brought word that the Meggido army was awaiting him on the Plain of Esdraelon, in front of the hill fortress of Megiddo. So in early May, with his communications back to Egypt secured by his navy, Thutmose swung inland, toward the small village of Yaham.

In front of Thutmose now rose a line of low hills, stretching from the northwest (Mt. Carmel at 1,740 feet) to the southeast (Mts Tabor & Gilboa, 1,929 feet). Megiddo and the Canaanite army were on the northern flank of these hills, and his generals told Thutmose there were two possible routes to attack Megiddo.

In front of Thutmose now rose a line of low hills, stretching from the northwest (Mt. Carmel at 1,740 feet) to the southeast (Mts Tabor & Gilboa, 1,929 feet). Megiddo and the Canaanite army were on the northern flank of these hills, and his generals told Thutmose there were two possible routes to attack Megiddo.

The most direct route headed due north from Yaham and then turned northwestward on the Via Maris (sea route) to the village of Taanach, before reaching Megiddo. The longer path headed northwest from Yaham along the flank of the mountains before crossing the hills to reach the valley at the village of Yokneam. From there it was an easy backtrack southeastward to Megiddo.

The Canaanite army had divided their infantry, with almost half guarding Taanach and the other half Yokneam. Stationed at Megiddo (in the center) were the Canaanite chariots with some infantry support, ready to fall upon either approach the Egyptians made.

However there was also a third choice. On the road north toward Yokneam there was a cutoff, a path less traveled, that ran through the village of Aruna (above, center) and then through a narrow defile, so tight that the army could pass through only single file, before debauching onto the valley directly in front of Megiddo. It was the most direct route, but Thutmose’s men would arrive piecemeal, where they could be destroyed “in detail”, one unit or even one man at a time. But this route also offered the opportunity of surprise.

It seems that Thanuny feinted toward the two main roads, using perhaps two thirds of the army. But before dawn Thutmose lead his spear and shield men through the pass, single file; perhaps 3,000 men in all. When they stepped out of the pass it was about 1:00 p.m., 9 May , 1457 B.C.

The Canaanite chariots, surprised by their enemies sudden appearance, hastily charged at the Egyptian spearmen, and let loose a barrage of arrows. But defended by their shield men, the Egyptian formations stood firm. And then, as the Canaanites withdrew to reform and attack again, the Egyptian ranks opened up and from the defile appeared Egyptian chariots, carried through the pass and reassembled, Like a whirlwind they fell upon the fewer Canaanite chariots.

“Even when moving at a slow pace, …(the Egyptian war chariot) shook terribly, and when driven at full speed it was only by a miracle of skill that the occupants could maintain their equilibrium…the charioteer would stand astride the front panels, keeping his right foot only inside the vehicle…the reins tied around his body so he could by throwing his weight either to the right or left…pull up or start his horses by a simple movement of the loins…he went into battle with bent bow, the string drawn back to his ear…while the shield-bearer, clinging to the body of the chariot with one hand, held out his buckler with the other to shelter his comrade.” (History of Egypt Chakdea, etc. G. Maspero. Groilier Society)

The Canaanites panicked at the sudden Egyptian charge, and their causalities tell the story; just 83 killed, but 240 taken prisoner and 924 chariots and 2,132 horses captured.

The Canaanite infantry on the wings, now divided by the Egyptian chariots in the center, abandoned Megiddo and scattered in retreat.

And although the fortress held out for seven months before finally surrendering, from the moment Thutmose III reached the valley he had ensured his capture of the hill fort of Megiddo, or, in the Canaanite language, Armageddon. And thus ended the first battle recorded in detail in history.

No one came to Meggido's rescue (above). The surrounding Canaanite cities were not likely to rush now to defend their defeated fellow Philistines. All of northern Canaan and many Syrian princes now sent Thutmose III tribute, and even their sons to serves as hostages,

But this first campaign was just the first of 17 campaigns for Thutmose III. The following year he finished his conquest of Mittani, even crossing the Eurphates River. Now the Assyrians, the Babylonians and Hittite Kings sent him tribute. During his entire fifty-three year reign, Thutmose III captured 350 cities, subjected many peoples, and dominated the middle east from the Euphrates River to the fourth cataract of the Nile. Under his reign, the Egyptian Empire reached it's greatest expanse.

He rebuilt much of Karnak, along with 50 other temples up and down the Nile.

Thutmose III (above) died in the 54th year of his reign, some 3,500 years before today. He was entombed at Luxor (below). He is remembered, for good reason, as "The Napoleon of Egypt".

- 30 -

.jpg)

.jpg)

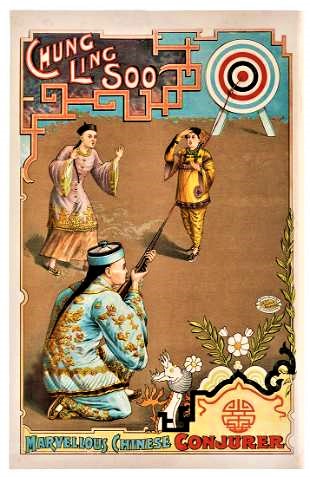

The inquest had also determined that Soo, the other “Original Chinese Conjurer” , was not actually Chinese. His actual name

The inquest had also determined that Soo, the other “Original Chinese Conjurer” , was not actually Chinese. His actual name

- who by the way actually was Chinese but was actually named Chee Ling Qua. (Confused yet?) The lesson here is that the only people who can trust magicians are their rabbits.

- who by the way actually was Chinese but was actually named Chee Ling Qua. (Confused yet?) The lesson here is that the only people who can trust magicians are their rabbits.

There was a delay in gathering the army, and Thutmose did not leave Tjaru until February of 1457 B.C. His Egyptian army was mostly infantry, perhaps 10,000 men, divided into platoons of six to ten men each, consisting of a mix of bowmen and lancers.

There was a delay in gathering the army, and Thutmose did not leave Tjaru until February of 1457 B.C. His Egyptian army was mostly infantry, perhaps 10,000 men, divided into platoons of six to ten men each, consisting of a mix of bowmen and lancers.

In front of Thutmose now rose a line of low hills, stretching from the northwest (Mt. Carmel at 1,740 feet) to the southeast (Mts Tabor & Gilboa, 1,929 feet). Megiddo and the Canaanite army were on the northern flank of these hills, and his generals told Thutmose there were two possible routes to attack Megiddo.

In front of Thutmose now rose a line of low hills, stretching from the northwest (Mt. Carmel at 1,740 feet) to the southeast (Mts Tabor & Gilboa, 1,929 feet). Megiddo and the Canaanite army were on the northern flank of these hills, and his generals told Thutmose there were two possible routes to attack Megiddo.

.jpg)