The engine's stealthy approach to Kennisinton station was unmasked with a deafening burst of steam. The startled crowd shouted obscenities. A fireman leapt from the engine and ran toward the black switching stand between the tracks. Individuals broke from the throng to stop him and he was forced to swing his switching rod to ward them off. Another handful of figures bolted for the engine and mail car. The railroad agents aboard shouted a muddled threat. And as the host reached for a handhold, shots rang out. The fireman broke free and was pulled back aboard as the black beast laboriously retreated whence it had come, leaving two dead and several wounded on the ground.

Also a victim of this brief confused shoot out at Kennisinton station was the American Railroad Union and it's president, Eugene V. Debs. And amazingly, yet another victim, shot in the foot actually, was the Democratic Party and its President of the United States, Stephen Grover Cleveland.

Just after dawn the day before, President Debs had been awakened by Federal Marshals, delivering the injunction issued by Judge Grosscup. The court order said while the owners of the railroad could act in unison, the workers must not. Reluctant to support the strike in the first place, Debs and the other leaders of the A.R.U. had sent over 4,000 telegrams urging the 125,000 strikers on 29 separate railroads across the nation, to remain peaceful. Now they were forbidden to speak at all. That afternoon, on 4 July, when the injunction was publicly read out by Federal Marshals, the crowds at the Grand Crossing were unimpressed.Also hearing the injunction on that Wednesday, were 2,000 members of the U.S. 15th infantry regiment, with artillery and cavalry support, ...

...all under the command of the vain and ambitious Major General Nelson Appleton Miles. His soldiers first occupied the empty Pullman factory.

The soldiers had no training in policing, but that suited General Miles, who saw his mission as a war against unions in defense of western civilization. Miles broke his men into squads and paired them with equal sized posses of railroad agents wearing badges - men the U.S. Marshal for the northern district of Illinois, John W. Arnold, called “worse than useless”.

Just before 4:00pm, Thursday, 5 July, one of Mile's joint posses approached Kennistion station again, this time aboard a Burlington and Ohio train.

As the engine, tender and mail car approached 47th street and Loomis, they encountered an even larger crowd, angered by the morning's deaths and intent on blocking the tracks with railroad cars and a locomotive purposely derailed. Rocks were thrown, immediately, and again the “authorities” joined the violence - the soldiers firing from 2 to 6 rounds apiece while the marshals emptied their revolvers into the the crowd. Six more were killed on the spot.According the Chicago newspapers, among the 20 or so wounded were “Henry Williams, shot in the left arm, Tony Gajewski, shot in the right arm, John Kornderg, stabbed with a bayonet and not expected to live, an unidentified woman, shot in the right hip, an unidentified man, shot through the liver and not expected to live, and an unidentified 17 year old boy shot in the stomach and expected to die.

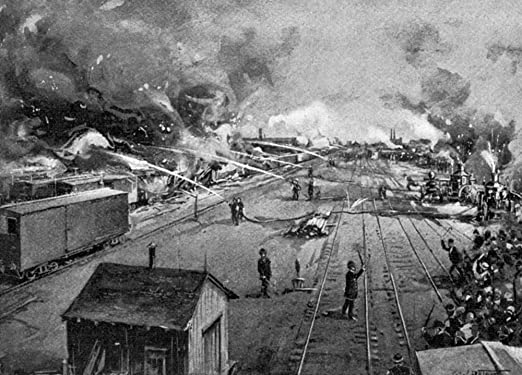

Now that blood had been drawn, on Friday, 6 July, General Miles reformed his men into battalions and dispatched one to the 375 acre Chicago Stock yards. Their presence allowed trains, and Pullman Cars to pass. As night approached, a frustrated mob of 6,000 vented their anger instead on the smaller less protected northern extension called the Panhandle Yards. It earned it's nickname because the Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, Chicago and St. Louis Railroad, which owned and operated the property, was based in the southern suburbs of Pittsburgh – in the northern panhandle of West Virginia.

On this Chicago site hundreds of mostly empty cars were resting, guarded by just 12 policemen. The officers were shoved and bullied, but none were seriously injured, and no shots were fired. The rioters systematically set the entire rolling stock ablaze.

Two companies of the 15th Infantry charged into the crowd, firing volley after volley. Several blocks away, saloon owner John Kerr, was wounded while tending to his customers. That bullet had passed through four walls to strike him. Innocent spectator William Anslyn, was over a city block from the confrontation when he was shot in the back. Two days later he died. Another spectator, elderly Charles Klynenberg, was standing in front of his own home at 4847 Loomis Street when a soldier charged up the street. Klynenberg ran toward his front door but was stabbed three times in the back. He died within minutes. A young woman, standing on her roof a block away was shot and fell dead, into her brother's arms.

Validation for the worker's version of the Pullman shootings of 1894 could be found in the Presidential Commission on the 4 May, 1970 shootings at Kent State University.

Under similar conditions, 28 members of the Ohio Nation Guard unleashed 67 rounds on about 2,000 protesters. Four were killed on the spot, another 9 were wounded. The closest wounded demonstrator to the soldiers was Joseph Lewis Jr. He was 71 feet away from the soldiers, and was unarmed.

The closest fatality was Jeffrey Miller, who was 265 feet away. The commission concluded, “...the indiscriminate firing of rifles into a crowd...were unnecessary, unwarranted, and inexcusable.” And the same could be said for the 1894 official murders committed in the name of protecting railroad property, and crushing workers seeking justice for fellow workers.

That night, General Miles told the press, “...the injured men are alone to blame....The firing...was strictly in accordance with orders from this office, (and) was necessary for the public welfare and justified by the circumstances. I think now that the mob knows that the troops will fire without hesitation when ordered. The trouble is nearly over.” And it was, for the railroads.

Said Col Thomas A. Anderson, “The army is not an enemy of Labor nor a friend of Capital. It is simply an instrument of popular power.” But nobody believed that version of reality anymore.

Almost from the day it opened, the Columbia fair grounds had suffered numerous fires, including one on 11, July 1893, in which 16 had died. Large sections burned again in January of 1894. Still, without any evidence, the press in July of 1894 , and most historians since, have blamed the strikers.

The quality of the deputized “Marshals” would be shown the very next day, Saturday, 7 July, when Deputy Marshal T.J. Ketcham accidentally shot and killed fellow deputy marshal Donald G. Goodwin while in the safety of their offices. But the truth did not matter much anymore.

The General Managers practice of attaching Pullman cars to even coal trains had brought rail traffic to a halt across much of the country. Factories were closing, because of disruptions to the supply chains, putting millions out of work. Seeing public support for the Pullman workers evaporate, Eugene Debs offered a sad compromise, asking only that his A.R.U. members be rehired. Instead the G.M.A. hired scabs.

On that Saturday afternoon came yet another bloody confrontation at 49th and Loomis Streets. Hit with rocks the 2nd Regiment of the Illinois National Guard fired a hundred rounds into a mob and followed it up with another bayonet charge. When the mob finally dispersed, they left a hundred dead and wounded on the ground, with an unknown number of wounded carried off.On Wednesday, 11 July, 1894, Debs and three other A.R. U. officials were jailed, charged with conspiring to “interfere with the transport of the mails, and violation of the Sherman Anti-Trust Act, which had been intended to be used against corporations, like the railroads. They were also charged with violating the injunction. The strike then quickly fell apart, and by the middle of August it was all over. The railroads lost over a million dollars in damages to equipment and another $80 million in lost revenue. But they smashed the A.R.U. and set worker's rights back for another half century.

Although defended by Clarence Darrow, Debs was sentenced to 6 months in federal prison. He came out a proud socialist, calling not for strikes but revolution.Grover Cleveland tried to sooth enraged workers with the creation of a worker's holiday, Labor Day. But the memories of murder and betrayal ensured that Cleveland would be last Democratic President until 1912, when Theodore Roosevelt's Bull Moose party split the Republicans and let Woodrow Wilson slip back into the White House. But after that brief aberration, it would take the Great Depression to break the Republican stranglehold on the Presidency,

The man who had started it all, George Pullman, died three years later, on 19 October, 1897. He was so fearful of workers seeking to insult his body that it took two days to pour the 18 inches steel reinforced concrete which still protects his coffin,

Working conditions on railroads after the strike would be shown by the fate of Howard F. Collins, the youngest son of Grand Crossing Superintendent Thomas Collins, who had tried to talk the switchmen out of striking on 25 June, 1894. After graduating High School in May of 1896, 12 year old Howard went to work as a conductor. Westinghouse had patented a pneumatic braking systems back in 1869, but like many railroads, the Illinois Central refused to pay the royalties to use. So, like all conductors, young Howard was required to clamber from car to car, to turn the brake wheel on each car in turn.

But on the Saturday night of 12 September, Howard was applying brakes for a train approaching the Grand Crossing, when, near 76th Street, he slipped and fell between the cars. The boy was dragged 36 feet. His right arm and collar bone were broken, his was spine severed. He died three days later, on 15 September. In gratitude for his father's sacrifice the Illinois Central carried the boy's broken body back to the family plot, in Ontario, Canada, For free. The Illinois Central did not fully use Westinghouse brakes until well into the 20th Century, when it was finally required to by law.

- 30 -

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please share your reaction.