I

think modern readers will be surprised to learn that congestion on

surface streets had driven Londoners underground as early as January

of 1863, when the first subterranean coal burning, smoke belching

steam engines began running on the 4 mile Metropolitan Line,

connecting Paddington, Euston and King's Cross railway stations. The Underground's passengers were breathing so much smoke

and foul smelling fumes, the management encouraged employees to grow

beards to act as air filters. Then they gave up and started calling

the atmosphere “invigorating”. It didn't matter. More than 11

million Londoners – out of a population of 3 million – hacked and

coughed up the 2 pence for tickets the first year of operation. After that,

a dozen private companies started raising money and digging tunnels

beneath the streets, fighting, merging and suing each other until

there were only two left.

The

first construction method was “cut and fill”, used for the new

sewers built a decade earlier. A trench was dug down the middle of a

street and tracks were laid in it. Then it was lined with bricks, and

covered over. But in 1866 “the shield” revolutionized subway

construction. A circular metal ring was hammered into the face of the

tunnel. “Navies” then dug out the soil within the shield (above), which

protected them during their work. Brick layers followed closely

behind, lining the tunnel as they progressed. Thus was born “The

Tube”, aka the London Underground.

The public fell in love with mass transit, and in 1887 the "North Metropolitan Tramsway Company" began laying tracks down both sides of the 100 foot wide Commercial Street (above). Historian Bernard Brown noticed one oddity if this project. "'The work continued day and night until completion in

November 1888. During the construction... Martha Tabram, Mary Ann

Nichols, Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride and Catherine Eddowes were

murdered...15th November 1888, a week

after Kelly s murder, the Commercial Street tramway finally opened

with a line of brown painted horse trams running between Bloomsbury

and Poplar (fare 3 pence). It is a highly speculative theory, at best.

The

construction was aided by the hard chalk soil of southern England,

which made tunneling easy, and a “laissez faire” labor market,

which made replacing injured or killed workers just as easy. But the

mindless competition between Met trains and District lines produced expensive duplication and delayed the first

underground service for Whitechapel until 1876.

With stations along

the High Street at Aldegate, St. Mary's Matfelon Church and

Whitechapel Station (above), next to the Working Lads Institute (above) and across

the road from the London Hospital, made attending the Coroner's Juries investigating the Whitechapel

murders, convenient for members of the press and public.

Attendance

had been growing since the August murder of Martha Tabram, and on

Monday, 10 September, 1888, the upstairs meeting room of the Working Lads Institute (above) was jammed. The

first witness at the Annie Chapman inquest was John Davis, who

recounted his discovery of the body. But the second witness was the

widow Amelia Palmer, who had known the 47 year old “Dark” Annie "a

short plump, ashen-faced consumptive" for 5 years, and had last seen her on the afternoon of Friday, 7

September, in the kitchen of the Dorset Street doss house where they

both slept.

In

the slang of Whitechapel the short, cramped brutal east/west block

between Commercial and Crispin Streets (above) was known as Doss Street- a

doss being a cheap bed, originally just a bundle of straw thrown on

the floor. On an average night 1,200 men and almost as many women

were sleeping in the stinking filthy dormitories along Dorset Street (above).

The only business on the street not making a profit by renting coffin

spaced “beds” at 8 pence a night was a grocery store at number 7

and the Blue Boy pub at number 32.

As Manhattan had it's Needle Park

in the 1960's, Whitechapel had it's “Itchy Park”, opposite the eastern end of Dorset Street, across Commercial Street, in what had once been the graveyard of

Spitalfields Christs' Church. There gangs waited even in daylight - "mug hunters" - who watched in the dark for a robbery victim's face to shine, which gave rise to the term mugger - "demanders" - who bullied their victims - or "Bludgers" - who beat or garroted any man woman or child who might have money in their pockets, It was the darkest dark corner of Whitechapel, and

Bobby's were assigned the night beat on Dorrest Street only in pairs.

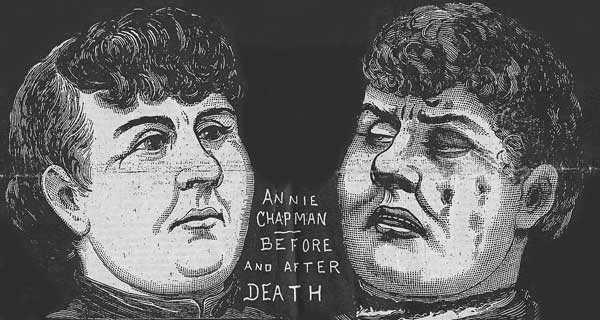

According

to the pale, dark haired Amelia Palmer, Annie Chapman (above) had been ill

for years, and most Fridays she sold crochet work and flowers.

But

this Friday Annie (above) was so sick she did not have the strength. Amelia said her friend

had put on a brave face, insisting, “It's no good my giving way. I

must pull myself together and get out and get some money or I shall

have no lodgings.”

Mrs.

Palmer was followed on the stand by Timothy Donovan, who worked at a

the 35 Dorset Street doss house. At about 2:30 pm that Friday Annie

Chapman told Donovan she had spent part of the week in a charity

infirmary, and he had then given her permission to use the kitchen.

She was still there, eating a potato, 12 hours later at 1:45 a.m. Saturday

morning. When she confessed to not having the 8 pence for her “bed”, Donovan had chastised her, saying “You can find money for your

beer, and you can't find money for your bed." After stalling

for a few minutes, Annie gave up. She said, "Never mind, Tim; I

shall soon be back. Don't let the bed." The last he saw of

her, Annie Chapman was heading off to find 8 pence

When Coroner

Wayne Baxter (above)asked where he expected Dark Annie to find the money,

Donovan replied with the mantra of capitalism concerning the source

of all profits: “I do not know”, meaning, “I do not care.”

And

finally there appeared before the coroner's jury this first day the

most controversial witness – and certainly the most opinionated -

Doctor George

Bagster Phillips (above). He was a 53 year old physician for the power

structure, who had already spent half his life as a respected doctor

and since 1865 the official surgeon for Whitechapel “H” division

of the Metropolitan police. It was Dr. Phillips who gave physicals

for the staff at the Leman and Commercial streets and the Arbour

Square “H” station houses, even giving them their smallpox

inoculations in 1871.

Dr.

Phillips contended that he reached his own conclusions, and

"...ignored all evidence not coming under my observation."

The failing of that self imposed limitation would only become evident with time.

At 2:30 on the afternoon of the murder – less than 8 hours after his

first cursory examination in the back yard of 29 Hanbury Street -

Phillips performed his autopsy at the Montague Street mortuary. He

found the victim's face was swollen, and had old bruises. But the

throat had been slashed, left to right, he thought, leaving “two

distinct cuts” two inches apart in the spine.

Dr.

Phillips offered the opinion that Annie was not a drinker, and she had not alcohol in her stomach. What had

slurred Annie's speech and caused her to stagger, was damage

to her brain caused by the loss of oxygen over years of suffering

from an advanced case of pneumonia - modern day COPD. She had very little food in her

stomach, and was also suffering from malnutrition. In short, when she

had been murdered, Annie Chapman was already within weeks of dying.

As

to what specifically had killed her that morning, Dr. Phillips was

equally certain. The murderer had first strangled Annie, perhaps

with the handkerchief found around her neck, if not to death at least

until she was unconscious . This caused her face to swell up and her

tongue to protrude. Only then had he slashed her throat, grabbing her

by the chin with one hand and swinging the knife left to right with

the other. This had happened 2 to 3 hours before examination, at 6:30

that morning – putting time of death between between 3:30 and

4:30, the morning of Saturday, 8 September, 1888.

After

death, said Dr. Phillips, the victim's legs were shoved apart. Her

dress was pushed up above her waist, and the killer had sliced her

abdomen fully open. The intestines had been cut free from the colon,

lifted from the body and placed or tossed over her right shoulder.

The uterus “and its appendages”, the upper portion of the vagina

and 2/3rds of the bladder were all removed. And they were gone. Said

Dr Phillips, "Obviously the work was that of an expert - or one,

at least, who had such knowledge of anatomical or pathological

examinations as to be enabled to secure the pelvic organs with one

sweep of the knife."

And

with that horrifying testimony, the jury adjourned for the day, not to

reconvene until Wednesday, 12 September. The certain Dr. Phillips

did not return for the second day of testimony, so he missed the

witnesses who destroyed his positive time of death estimate.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please share your reaction.