I admit that it would be an

oversimplification to say Detroit became the center of the American

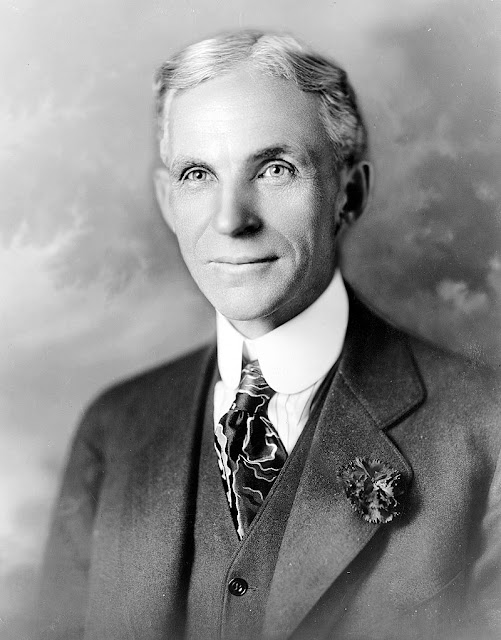

auto industry because in 1863, Henry Ford (above) was born in it's suburb of

Dearborn, Michigan. That accident of birth may have been why, out of

the thousands of backyard inventors and tinkers it was Henry who in

just 30 years went from failure to earning the modern equivalent

$188 billion. But the real key to Detroit's success was just good

old geography.

See, in 1900, there were 8,000

automobiles in America,built by over 1,000 inventors from Bangor,

Maine to San Francisco. But a realistic look at the market showed

that if you wanted to be successful at making cars you needed six

things – steel, coal, rubber, cheap land for your plant, workers

and customers. And it turned out that 1900 Detroit, was the perfect

time and place for all those things to come together. Well, not

perfect. It was a compromise, but as compromises go, it was perfect.

First, if you want to make steel, you

need iron ore, and around the northwestern edge of Lake Superior –

in the forests of Minnesota, Wisconsin, Ontario, Canada and the upper

peninsula of Michigan – were some of the world's richest outcrops

of soft cherty iron oxides.

Humans started mining this iron in the 1840's, when the ore was so

rich it could go straight into a smelter.

They started out producing

iron right next to the mines, heating the ore over wood fires to over

2,000 degrees Fahrenheit and then scraping off the impurities. But

you can't make an automobile out of iron. You need steel.

The

forests that surrounded the mines might have supplied enough fuel to

turn that iron into steel, but burning one pound of wood only gives

you about 7,000 British Thermal Units of heat. However burning a

pound of coal produces almost 3 times as many BTUs. The problem was the nearest

coal deposits were 1,500 miles and more to the south.

Ships being the

cheapest method to carry bulk cargoes,investors, mostly from

Cleveland, Ohio, built fleets to transport ore out of Lake Superior,

through Lake Huron to the bottom of Lake Michigan and Lake Erie. Where in the 1840's they could connect to the Erie Canal and reach New York City.

In

1903, at the age of 39, Henry Ford had his third try at making

automobiles - The Ford Motor Company. Henry had little money left to

invest, and was installed as Vice President of his own company. The

new factory (above) was in the Milwaukee Junction neighborhood of Detroit,

and it was already home to a few other would-be automakers. But the

largest industry in town was making heating and cooking stoves. Which they made out of iron.

Ford

Motor Company's first car, the Model “A”, was a 2 seat “runabout”

with an 8 horse power engine under the driver's seat. It only came

in one color – red – and was advertised as “The most reliable

machine in the world”, which it was not. Still, Ford sold 1,708

cars in 1903, and was able to offer an improved model, the “AC”,

in 1904, with a 10 horse power engine. That year they also

introduced the Model “B”, with it's 24 horsepower engine up

front. But the “B” cost 3 times what the Model “A” did, and

did not sale well.

In 1900 the southernmost port on Lake

Michigan was Hammond, Indiana. And about 60 miles due south of

Hammond was the Kankakee Arch, the northern rim of the 500 million

year old subterranean Illinois Basin. It lies under most of Illinois,

half of Indiana, a big chunk of Kentucky and a sliver of Tennessee.

Since 1900, the basin has produced well over 8 billion tons of coal.

By 1901, the furnaces of Hammond were

importing 2 ½ million tons of iron ore every year. A new port was constructed

30 miles to the east, to serve what became 6 steel mills pouring out

smoke from the Illinois border the U.S. Steel's new mammoth plant in

Gary Indiana.

They called it the Calumet Steel District, and it

boasted 37 open furnaces, 8 blast furnaces, with endless lines of

rolling mills that would employ 200,000 workers, producing, in 1925,

some 8 ½ million tons of steel. And since the rail roads were

already delivering coal to the Calumet, it was a minor investment to

extend those rails to new electrical generating plants in Chicago.

In 1906, Ford introduced the luxury

Model “K”, powered by a 6 cylinder, 40 horsepower engine. They

sold less than 1,000 Model K's but the profit margin per car was high

enough to make the “K” successful. Despite this Henry was more

enthusiastic about his 4 cylinder Model “N” (above), which sold over

2,190 cars in 1906. That year, Henry bought out the chief supporter

of the Model “K”. Alexander Malcomson. And as the new President

of the Ford Motor Company, Henry was now free to discontinue

production of the “K”, and pursue

his dream to “Democratize the Automobile”.

A

little over 200 miles southeast of Detroit, and about 40 miles south

east of Cleveland, on the western edge of the Pennsylvania

coal fields, is Akron, Ohio. Dr. Benjamin Franklin Goodrich had moved

his rubber manufacturing company (above) to Akron in 1875, because of the

cheap land, convenient canals and railroads, and the labor supply. But mostly because 25 feet under the sandstone foundations of Akron,

there was a lot of coal.

See,

back in 1860, the British chemist Charles Greville Williams had

described the chemical that made rubber act like rubber – latex.

And once described in living plants, the same molecules were quickly

found in dead plants – like coal. In particular the kind of coal

underlying Akron, Ohio.

The new synthetic latex wasn't as good as

natural rubber. It was better, because in cooking up each batch, you

could tweak the recipe for whatever product you were making – like

fire hoses or rubber gloves (above) or tubing...

...or tires and inner tubes for the 1890's bicycle

craze. And with that was why Akron, thousands of miles from the

nearest rubber tree plantation, became the “Rubber Capital of the

World”.

The

bicycle craze brought new companies to Akron, like Diamond, Universal, and

Goodyear, and, in 1900, a buggy wagon salesman named Harvey

Firestone. (above) Harvey decided to specialize in mass producing pneumatic tires for

buggy's and wagons. Many a farmer's ass thanked Harvey Firestone for

that innovation.

And, in 1907, when Henry Ford (above, left) went looking for

somebody who could supply enough tires and rubber belts and gaskets for his

“car for the multitude”, Harvey (above, right) was the right man in the right

business.

In

January of 1907, the 44 year old Henry Ford set up a work shop on the

third floor of his factory to design his new car. It had to be simple

to assemble and cheap to build. Henry wanted it to be light enough,

simple enough and rugged enough that the average customer could

maintain it by himself. It had to survive the rutted and pockmarked

unpaved roads of America. Presented to the world in the fall of

1908, it would be Henry Ford's Model “T”.

That

same year Henry bought a factory 4 miles north of Detroit in Highland

Park, Michigan, from the Dodge Brothers - who had been building

engines there for Ford - Henry also acquired 60 adjoining acres of

farmland. Here he would build a massive new factory (above), large enough to

allow him to experiment in assembling his Model “T”.

It was here

the Industrial Assembly Line would be born, and all but a handful of

the 15 million “T” Fords would be built here, gobbling up the steel from the Calumet mills and rubber from Akron..

Owners

called her the Tin Lizzie, the Bouncing Betty and the Mechanical

Cockroach. The “T” had no fuel pump, so you had to drive uphill

in reverse. It had no oil pump. Crankcase oil splashed up onto the

cylinders, as well as down onto the ground. To avoid excessive

breakage, each linkage of the chassis had a generous amount of

“give”, which resulted in a very talkative car .

How

do you tell the difference between a rattlesnake and a Model “T”?

You can count the rattles on a snake. Owners did not need a

speedometer. At ten miles an hour the hood rattled. At fifteen the

radiator rattled. At twenty the top rattled. And at twenty-five miles

an hour the transmission fell out.

It was alleged Henry Ford was

training squirrels to run behind each new Model “T” to collect

the nuts as they fell off.

Model “T”s came in only one color –

black. But, went another joke, why did they paint Chevy's Green? So

they could hide in the grass and watch all the Fords go by.

However, one owner

insisted he wanted to be buried in his Model “T”, because “its

gotten me out of every hole I've ever been in.”

Three

hundred and fifty miles almost due south of Henry Ford's new factory,

was the college town of Bloomington, Indiana (above) . In 1910 it had less

than 10,000 inhabitants, whose primary occupations were farming,

quarrying the local limestone, making furniture, and tending to the

residents of Indiana University. The town boasted a new courthouse, 5

churches, 2 railroad stations, 2 theaters, and a new library. I.U.'s

claim to fame was coach James Sheldon's team which did not give up a

single touchdown during their 6 and 1 season. But Bloomington had yet

another reason to celebrate the year of 1910.

Near

the corner of North Rodgers and West 8th

Street, the United States Census Bureau had calculated was the exact

physical balance point of the 92,228,496 American citizens enumerated

in the 1910 census.

In short, half of Henry Ford's potential

customers lived east of Bloomington, and half west. And half of his

potential customers lived north and half lived south of this

imaginary fulcrum - 39 degrees, 17 minutes north latitude and 86

degrees 53 minutes west longitude.

In

the decade Henry Ford was building his company that center had

shifted west 36 miles from outside of Columbus, Indiana to

Bloomington. In the coming decade of the Model “T”, it would

shift another 28 miles west northwest to just outside of Spencer

Indiana. And by the time they finally ended production of the Model

“T” in 1928, the center of the customer pool would have moved

another 31 miles west southwest to the little town of Linton,

Indiana. Each following decade, the center of the customer base would

move a little farther from Detroit and farther from Henry Ford.

Henry

supposedly retired in 1918, turning control over to his son, Edsel.

But that was just a scam, to remove his opponents from the board of

directors. By the time America became involved in World War Two,

Henry's corporation had produced more than 29 million automobiles.

But he had suffered a series of strokes in the late 1930's, and Edsel

became the true president of Ford Motor Company.

Then in 1943, Edsel

died of a stroke, and Henry took up the reins again. But age and wear ate away at his attention span. Under his tenure

Ford Motor Company lost $10 million a month. As his mind faded, his

daughter-in-law sued to take control of his company, and installed

Henry's grandson, Edsel Ford II as new president.

Henry

Ford died in the waning moments of Monday, 7 April, 1947, at 83 years of age. His funeral procession (above) passed the headquarters of all the major automakers in Detroit, and their employees stood at the curb, to pay homage to the man who had built their industry.

Henry Ford was a life long antisemitic, and used his fortune to finance

antisemitism worldwide. He also built the first mosque in the United States, for his Muslim employees. He did business with Nazi Germany, and Hitler

praised Henry in speeches. At home, Henry paid thugs

to brutalize labor union organizers. He also hired African Americans, and paid them equal to white workers. He was suspicious of

mathematics, and as long as he was in control, Ford Motor Company was

never audited. Perhaps Henry's ignorance was understandable, since

his mother had died when he was 12 and his father had forced him to

leave school at 15 to work on the farm. He hated his father's farm. It was why the publicity department at Ford Motor Company usually photographed Henry in his machines. He understood machines.

In

short, Henry Ford was a human being, smart and stupid, kind and

cruel, arrogant and humble, sometimes in the same moment. He worked

hard every day of his life. He was very rich, but wealth merely

magnified his faults and strengths. What made Henry Ford one of the

richest human beings on the planet, had surprisingly little to do

with Henry. It was really just geography.