I think some of the 300 troopers saw the danger. But momentum carried them up the narrow road and into the blind curve, past the 2 story farmhouse of Mr. Dallas Furr on the left, past the low stone wall on the right where some of the killers crouched, to the top of the rise and into the killing zone. In the time it takes to draw a breath 2,000 Virginians rose and fired a single murderous volley, from front and rear, punctuated by a point blank cannon blast of grapeshot. In the words of the First Massachusetts regimental history, “In a moment the road was full of dead and dying horses and men, piled up in an inextricable mass....All who were not killed were captured,” says the history, “except a very few...in the rear of the squadron.” Those few survived. But they never forgot the bloody ambush at Aldie, Virginia.

Just after midnight of Wednesday, 17 June, 1863, “Fighting Joe” Hooker passed on some of the heat he had been getting from Washington to his cavalry corps commander, Brigadier General Alfred Pleasonton (above). Hooker's orders were brutal. “The Commanding General relies upon you...to give him information of where the enemy is...Drive in (their) pickets, if necessary and get us information. It is better that we should lose men than to be without knowledge of the enemy.”

Fired with this new urgency, at 3:00 a.m. Pleasanton dispatched 30 year old, 6 foot 1 inch Brigadier General David McMurtrie Gregg (above) to take his 2nd cavalry division and occupy the “quaint and picturesque” village of Aldie.

The Federal stupidity at Winchester allowed Robert E. Lee to gamble. He ordered Longstreet's First Corps not to follow Ewell's safer road through the Chester Gap and into the Shenandoah Valley, but to take the quicker route, east of the Blue Ridge, and be quick about it. It was a blazing hot Tuesday, 16 June, 1863, when the First Crops' of the Army of Northern Virginia, 21,000 men, set out on a 12 hour quick-step march. Choking on their own dust clouds, over 500 rebels dropped from heat exhaustion. But by dark the First Corps had covered almost 30 miles, and the advance had reached the town of Upton, Virginia, almost at the mouth of Ashby's Gap. And with that forced march a village 40 miles away, on the east side of the Loudoun Valley, became, briefly, a place men would die to posses.

At just about 10:00 on the hot, humid morning of 17 June, Major General J.E.B. Stuart (above) and his staff rode into the village of Middleburg, in the center of the Loudoun Valley.

Closely following were 5 Virginia cavalry regiments, commanded by Col. Thomas Munford (above) and supported by Captain James Breathed's battery of 5, 3 inch rifled horse artillery.

Stuart was under orders to blind the Yankees to Longstreet's march. So about noon, after allowing the troopers and horses 2 hours to cool down and water, Stuart dispatched the Virginians 5 miles further eastward to plug the Aldie gap in the rolling Bull Run Mountains.

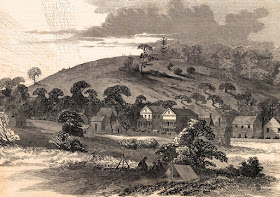

Munford held the 1st and 3rd Virginia regiments about a mile west of the pass as his reserve, and to collect forage for the brigade's horses. The 2nd and 4th regiments took the Carter's Bridge cutoff – now the Cobbs House Road - to reach the Snickersville Turnpike north of Aldie (above).

The 5th Virginia regiment continued through the pass alongside the Small River and arrived in the little village of 145 souls about 2:30 that afternoon, just as the Federal Cavalry Brigade of Colonel Judson Kilpatrick appeared through the heat shimmers.

Killpatrick (above) had 1,200 troopers under his command – first in line was the 2nd New York, followed by the 6th Ohio, the 1st Massachusetts and then the 4th New York volunteer cavalry. An hour behind was the Second Brigade, commanded by the Division commander's cousin, Colonel “Long John” Irvin Greeg, leading the 1st Maine and 4th Pennsylvania volunteer regiments. A collision was not only inevitable, it was just what Colonel Judson “Kil-cavalry” was looking for.

The New York boys chased the rebels out of Aldie. Then rebel Colonel Thomas Rosser brought his Virginians in force and chased the Yankees back down the pike.

In response the 6th Ohio went into formation, and together the 2 Federal regiments drove the 5th Virginia back beyond the road junction with the Snickersville Pike, thus opening up both roads for a Federal advance. Killpatrick had his 2 leading regiments dismount to defend the Ashby Pike, and sent the Massachusetts and 4th New York boys up the Snickersville pike, to outflank the Virginians.

The Massachusetts troopers skirmished with the 2nd and 4th Virginian until about 3:30, slowly driving the rebels back to their main line of defense, the hilltop stone fences and house of the Furr family farm. Colonel Munford, who personally organized the defenses on the hilltop, said, “I doubt if there was a stronger position in fifty miles of Aldie than the one I had.” South of the Furr house, across the fields, Companies E and G of the 1st Massachusetts formed in column of fours and charged straight up the turnpike, with the 4th New York attacking across the fields. As the temperature topped 94 degrees Fahrenheit, those on the road quickly outpaced the New Yorkers crossing the fields.

When rebel Sargent George Brooke and his fellow Virginians stood and fired, he was so close he could see the dust fly off the blue jackets of the Massachusetts boys, as rounds from nearly 2,000 carbines and revolvers penetrated. It was impossible to miss.

On the other side, Corporal John Weston wrote his sister, “We were flanked on the right and left...firing into us a perfect hail of bullets. Let me turn my head which way I would, it was horses and men falling..."

"The road was narrow...all blocked up with wounded horses with their legs broken, kicking and floundering among men and horses dead and dying. If a wounded man fell among them there was not much chance for him. I can't see for my life how any of our squadron got out..” Few did. The slaughter was memorable even to men in their third year of war.

Piled high at the blind curve were the bodies of 24 officers and men, 42 wounded and another 88 unable to escape before being taken prisoner. On the Rebel side, Colonel Munford would later write, “I have never seen as many Yankees killed in the same space of ground...on any battlefield in Virginia that I have been over.” A Federal doctor was more succinct, calling the fight at Aldie, “by far the most bloody cavalry battle of the war.” Another rebel officer noted, “I had never known the enemy’s cavalry to fight so stubbornly or act so recklessly, nor have I ever known them to pay so dearly for it.”

The lead elements of Colonel Gregg's 2nd Battalion, the First Maine cavalry, arrived to stabilize the Federal line, and by evening the Confederate troopers were forced to withdraw from the Aldie pass and fall back toward Middleburg, where they discovered an understrength Yankee Rhode Island regiment had captured the town in a rush, almost taking Stuart and his entire staff prisoners. Then the Islanders had grimly held on until relieved by the General Gregg's division, after dark.

The opposing cavalry spent Thursday, 18 June, pushing each other into and out of Middleburg. But by the end of the day, General Pleasanton's gathering cavalry corps had pushed westward, closer to the masking Blue Ridge. Pleasanton still didn't know what Stuart's troopers were fighting so hard to protect. And the only way he could find out was to keep pushing up the Ashby's Gap Pike until he could break through. But that made Stuart's job relatively easy – keep throwing fresh units in front of Pleasanton, to slow him down and cost him men. As night fell, a thunderstorm crashed over the Loudoun Valley, and rained into the morning of Friday, turning the unimproved roads and fields into quagmires.

Behind the cavalry screen, the unimpeded rebel march north continued. On Friday, 20 June, A.P. Hill's corps began crossing the Potomac River further downstream from Williamsport, where General “Baldy” Ewell's men were still striping the Maryland countryside of food and horses.

But the aggression of Pleasanton's horsemen had convinced Lee to hold some infantry back in the Shenandoah Valley, blocking Ashby's Gap and, 14 miles to the north, Snickersville Gap, through the Blue Ridge. And the units Lee picked to slow down and provide the blocking force were the 21,000 men commanded by his “Old War Horse”, Lieutenant General James Longstreet.

There were good reasons for the choice. Lee trusted Longstreet (above) to use his men wisely, avoiding a bigger fight than was absolutely necessary. And, after the forced march of 16 June, Longstreet's men could use a day or two of rest. But there might be other less laudable reasons for Lee to make “Old Pete” last in line for the invasion. Just a month ago Longstreet had urged the Confederate government to dismember Lee's Army of Northern Virginia,. That would also free Longstreet from Lee''s authority. And he had forced Lee to negotiate to win the argument. It also seems likely to me that Lee had begun to worry that “Pete” Longstreet might be too cautious once over the Potomac. The "Grey Knight" had no doubt that Longstreet would follow orders, but all orders are subject to interpretation. And subsequent events would seem to prove Lee right to worry. So the First Corps was held back to guard the passes through the Blue Ridge. Longstreet, the most experienced corps commander in Lee's army was thus last in, with the Division of Brigadier General George Picket as their tail-end-Charley

While the Massachusetts cavalry were bleeding that Wednesday, 17 June, Major General Joseph Hooker (above), commander of the Army of the Potomac, had worked himself into a new panic. He telegraphed his boss, General Halleck, “All my cavalry are out, and I have deemed it prudent to suspend any farther advance of the infantry until I have information that the enemy are in force in the Shenandoah Valley. I have just received dispatches from Pleasonton...He ran against...(rebel cavalry) near Aldie, and...it is further reported that there is no infantry on this side of the Blue Ridge...All my cavalry are out. Has it ever suggested itself to you that this cavalry raid may be a cover to Lee's re-enforcing Bragg or moving troops to the West?”

It was a most desperate fantasy - that Lee could slip away and vex and embarrass some other union general rather than General Hooker. General-in-Chief Henry Halleck (above) deflated that balloon with a telegram on Thursday, 18 June, “Officers and citizens...are asking me why does not General Hooker tell (us) where Lee's army is; he is nearest to it... I only hope for positive information from your front.”

Halleck's missive crossed with Hooker's (above) latest fevered paranoia - “I would request that signal officers be established at Crampton's Pass and South Mountain (in Maryland).” He had returned to his obsession with those isolated and under strength commands outside his control. By noon on Friday, 19 June, Hooker was again demanding that he be given authority over the few infantry and cavalry at Harpers Ferry and in the Cumberland Valley of Pennsylvania “I have asked...for information as to the location, character, and number of their commands. Please direct it to be furnished....Are orders for these commands to be given by me where I deem it necessary?”

During all of this fevered mental activity The Army of the Potomac – the 85,000 effectives that Hooker was actually responsible for - had been slowly shuffling north. The 12th crops under Major General Slocum was at Leesburg, Virginia, the 11th under General Howard was just south of there, the 5th Corps under General Meade was at Aldie, the First Crops under General Reynolds was camped around Herndon Station, the 3rd Corps under General Birney was at Gum Spring, the 2nd Corps under General Hancock was at Centerville, and the 6th crops commanded by Major General Sedgwick was at Germantown, Virginia. So both armies were on the move. But Hooker remained convinced that the Army of Northern Virginia had not yet crossed over the Potomac in force

And then, on the afternoon of Saturday, 19 June, General Hooker (above) asked his boss, “ Do you give credit to the reported movements of the enemy as stated in the Chronicle, of this morning?” Halleck forced himself to wait an hour before he responded. “I do not know to what particular statement in the Chronicle you refer. There are several which are contradictory. It now looks very much as if Lee had been trying to draw your right across the Potomac, so as to attack your left. But...it is impossible to judge until we know where Lee's army is. No large body has appeared either in Maryland or Western Virginia.”

Lee had stolen a week's march on Hooker. On Saturday, 19 June, he already had 1/3rd of his infantry across the Potomac, with another third about to cross. And Hooker remained confused and bewildered. It was not until late on Sunday, 20 June, that things clarified for Hooker, and it was the sacrifices of the cavalry which finally pierced the fog at Hookers headquarters. At 5:30 that evening he notified Washington, “Infantry soldiers captured report...that Longstreet's rear passed through the Blue Ridge yesterday. I have directed a bridge to be laid at Edwards Ferry to-night.” Hooker was finally following Lee north of the Potomac River.

- 30 -

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please share your reaction.