In mid May the new commander of the Trans-Mississippi – just 3 months on the job - 39 year old General Edmund Kirby “Seminole” Smith (above) , faced a mounting crises with shrinking resources.

Two years before, in March, the Confederacy had lost its most populous city, New Orleans. In April of 1862 the Yankees of had driven the government of what had been the richest state in the Confederacy from it's capital, Baton Rouge. In January of 1863 Smith had surrendered the new capital of Oposlusa. And in early May, from it's 4th capital Alexandria, on the Red River. Since March the government had been isolated 124 miles northwest of Alexandria, in the small town of Shreveport - half a mile to the east of Smith's headquarters at Fort Johnston, and just 40 miles from the Texas border.

The little capital of Shreveport (above) - between hills and the Red River - was jammed with about 6,000 whites and 3,000 slaves – almost double it's antebellum population. The Shreveport Arsenal, under Captain Frederick Peabody Leavenworth, was busily producing ammunition and repairing weapons, now with additional workers evacuated from the Arkadelphia, Arkansas Ordnance Works. But the only way to get that production to the armies was by horse drawn wagon. The Red River supply line was now blocked at Alexandria. The closest railroad to Shreveport was the line from Marshal, Texas - which stopped 5 miles short of town. The only other railroad came no nearer than Monroe, 100 miles to the east.

Almost 200,000 men from the Trans Mississippi were serving in Confederate armies - 60,000 from Arkansas, almost 60,000 from Texas, 50,000 from Louisiana, 30,000 from Missouri and 2,500 from New Mexico Territory. But by mid-May of 1863 all those men were beyond reach. Kirby Smith could muster barely 30,000 men in the Trans Mississippi. And those few were short of training, uniforms, food, ammunition and medicine because the “gray back” Confederate currency used to buy supplies was almost worthless. The view from Fort Johnson was so depressing, Smith began to consider resigning from the army and retreating into a Jesuit monastery.

Seventy miles southeast of Shreveport, at Natchitoches, commanding about 4,000 scattered men, was 36 year old Major General Richard Scott "Dick" Taylor. He had spent the spring being pushed up the Bayou Teche, even suffering the insult of having his own plantation burned to the ground. Even after Yankee Major General Nathaniel Banks withdrew 3 divisions down the Red River to attack Port Hudson, Taylor's army was still too small to confront the 10,000 Yankees as they backtracked down Teche Bayou to Brashear City, the western terminus of the railroad out of New Orleans. Never the less, the ex – President's son had a plan.

General Taylor would write after the war that as he re-entered Alexandria, he received word that, “...Major-General Walker, with a division of infantry (Walker's Greyhounds)...would reach me within the next few days”. Taylor had no doubt how best to use 4,000 fresh soldiers. “I was confident that, with Walker's force, Brashear City could be captured...(And when) Banks's communication with New Orleans..._(was)threatened....(this) would raise such a storm as to bring General Banks from Port Hudson, the garrison of which could then unite with General Joseph Johnston in the rear of General Grant.”

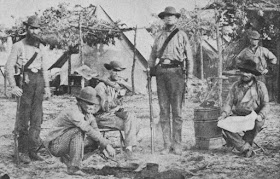

Major General John George Walker (above) was another of the qualified field officers in the Army of Northern Virginia who were transferred west in June of 1862, after Robert E. Lee took over in Virginia. So, in November, Walker took command of 12 Texas regiments in 3 training camps in Lonoke County, central Arkansas. The staging posts had originally been called Camp Hope, but in the fall 1862 measles and typhoid swept through the 20,000 recruits, killing 1,500 of them, including newly promoted Brigadier General Allison Nelson. Thereafter the soldiers referred to the place as Camp Death, but the War Department preferred Camp Nelson. Walker earned his men's respect by paying attention to camp hygiene, which cut the death rate by two thirds.

A brigade of the Texas Division, under Brigadier General Thomas J. Churchill, was detached to occupy Fort Hindman at the Arkansas Post in January of 1863, but was lost when that position was captured by Major General John Alexander McClernand. Until late April, Walker's men remained in central Arkansas, in case the Yankees made another strike toward the capital of Little Rock. But once General Smith could confirm that Grant had crossed the Mississippi to attack Vicksburg, he decided he could risk 6,000 of Walker's men to cut the Yankee supply line.

They set out on foot the morning of Friday, 24 April, 1863. Eight days and 78 miles later they crossed the border into Louisiana. They made 16 miles on Saturday, 2 May, and another 16 on Sunday, 3 May, camping that night on the banks of Bayou Bartholomew. Following that tributary south for 2 more days, and 15 miles, brought Walker's division to Washita, Arkansas, where they were met by a dozen steam boats, which carried them to the town of Trenton, opposite the town of Monroe, western terminus of the Vicksburg railroad. The 6,000 rebels camped that night, 2 miles south of Trenton. That night they informed General Smith they had finally arrived in the theater of operations.

While General Smith considered what to do with Walker's Texas division, local commander, and Texan, 44 year old Brigadier General Paul Octave Hébert, tried to pilfer a brigade for his own needs. But Walker was able to fall back on his orders from General Smith, to keep his division together.

Eventually, Smith decided it would be better to send the Texans back to Arkansas, where they would be safe from both the Yankees and sticky fingered Confederate generals. So at 8:00 a.m., on Saturday, 9 May, the 6,000 Texas soldiers re-boarded transports (above) for a return voyage to Washita. But as the boats headed north, General Taylor would re-direct Walker and his men to his join his southern assault on Brashear City.

The Texans waited until Friday, 15 May, for their supply wagons to arrive from Washita. The next day, Saturday, 16 May, as Grant's Yankees were driving Pemberton's rebels back behind the forts at Vicksburg, the Texas Division retraced their steps 17 miles southward. Over the next 8 days General Walker's Greyhounds marched 150 miles, finally reaching Alexandria, on Wednesday 27 May –which is when General Smith in Shreveport finally learned of Taylor's revival of his proposed advance down Bayou Teche.

Taylor would claim that both Confederate Secretary of War James Seddon and President Jefferson Davis had approved his fantastic, almost fantasy, plan to threaten New Orleans. But Taylor's boss, General Kirby Smith (above), did not. As they retreated from Alexandria, the Yankees had burned and destroyed everything in Cajun Country which might support an advancing rebel army. So Taylor's plan depended upon capturing Yankee supply depots to feed and arm his now 8,000 men, and that, in the opinion of General Smith, was not likely to happen. And even if it did, it would leave half of the Trans Mississippi army isolated in the far south west corner of the theater. Besides, Smith had been receiving an almost endless stream of orders from President Davis to do something directly to rescue Vicksburg – under cutting the claim Davis supported Taylor's fantasy.

General Taylor (above) whined, “ I was informed that...public opinion would condemn us if we did not try to do something.” So Smith's original orders stood. On Thursday, 28 May the Texans changed their line of march, now heading 40 miles over 3 days toward the port called Little River. There they prepared 2 day's rations before again boarding steamboats, this time heading north up the Tenas River.

Taylor and Walker were to advance toward Richmond, Louisiana, on the Shreveport and Vicksburg railroad, and strike from there to capture Young's Point and Milliken’s Bend, thus cutting Grant's supply line down the western bank of the Mississippi. Taylor remained skeptical. “The problem was to withdraw the garrison (of Vicksburg), not to re- enforce it”, he wrote. But in all fairness, that was not Smith's plan, either. He wanted to force Grant to withdraw from his positions in central Mississippi, by cutting his supply line.

The problem was that the week earlier, Grant had shifted his supply base to the Yazoo River at Chickasaw Bayou and Snyder's Bluff. So after a month's worth of exhausting marching and counter-marching, General Smith's plan had failed before it had ever been launched.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please share your reaction.