I doubt most Americans remember James Gadsden (above) . In 1840 this ex-army officer became president and primary shareholder in the South Carolina Rail Road Company. He had big dreams of a southern transcontinental railroad, beginning in Charleston and driving across Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas, all the way to the Pacific Ocean. There were only three things that stood in his way.

First, his railroad was only 135 miles long and went no further west than the Georgia border (north). Second, it was over $3 million in debt ($64 million today). And third, in 1840 everything west of Texas belonged to Mexico. But Mr. Gadsden was not willing to concede defeat before even starting. And because he was not, James Addison Reavis would have a golden opportunity to become one of the richest thieves in America – call it another unforeseen consequence.

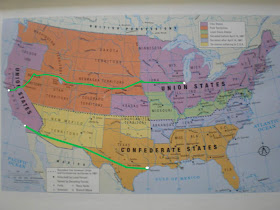

By 1840 there were two routes under consideration for the first transcontinental railroad. The central route, favored by the business interests in New York and Chicago. It started in Missouri and followed the trail blazed by wagon trains already heading to the newly discovered California gold fields. The route favored by Mr, Gadsden and most southern politicians, started in either South Carolina or Georgia. However, the southerners could not decide between themselves on how to finance the work. And Gadsden was too arrogant to form a consensus from his own allies. The only thing the southerners could agree upon was that they would not allow the central route to be used. So as long as the south had a veto, any transcontinental railroad would remain a dream.

The Mexican War (1846-1848) had given America a vast new empire north of the Rio Grande River, comprising what would be the states of Texas, California, Nevada, Arizona and New Mexico. But even this conquest failed to supply an acceptable route for a southern transcontinental railroad. And the "Compromise of 1850" made things even worse. In exchange for relieving Texas of its huge public debt, Texas came in as a slave state and California was admitted as a “free” state. After that, no matter who built the transcontinental railroad or where they built it - and they couldn't sidetrack into Mexico, because slavery had been outlawed there since the 1845 - the end of the line would now be a “free state”.

Desperate to lure the Golden State back to the slavery side, even it it required cutting it in half, in 1851 the argumentative Gadsden (above) offered to supply 1,200 new settlers, if California would also admit “not less than two thousand...African domestics” into southern California. The ploy fooled nobody, and the proposal never got out of committee in the California legislature. Defeated again, Gadsden decided to salvage what small part of the plan he still had some control over.

If he couldn't find a way around the Mexican border beyond Texas, Gadsden decided to move the border. With assistance from Mississippi's Jefferson Davis, who at the time was President Franklin Pierce's Secretary of War, Gadsden won appointment as an agent of the United States Government, authorized to buy a southern railroad route. Now, again, the one thing James Gadsden did not have were negotiating skills, and the minute he arrived in Mexico City and opened his mouth, he offended the entire nation of Mexico. But Gadsden was in luck, because at the time (1853), the entire Mexican government consisted of one ego maniac, General Antonio Lopez de la Santa Ana.

This was Santa Anna's sixth go around as President-slash- dictator of Mexico. He is remembered in America for his capture of the Alamo, and killing “Davy” Crockett. But in Mexico he is remembered because he never seemed to learn from his mistakes, which constantly seems to have surprised the Mexican people. Every time a crises occurred, they turned to Santa Ana, and he kept responding by looting the country and then burning it down to destroy the evidence. Typically, in 1853, Mexico was broke, and unable to pay her army. So no matter how many ways James Gadsden insulted him, and he did find many ways of doing that, Santa Anna could not walk away from the negotiating table, because Gadsden was offering cash money.

The resulting Gadsden Purchase acquired 30,000 square miles of fertile farmland, harsh desserts and valuable mineral deposits, and a railroad route over the lower end of the Rocky Mountains, all for the bargain basement price of $15 million – about thirty-three cents an acre. From the American point of view it was a great deal. From the Mexican point of view, it was rape. But really, nobody actually involved in the deal got what they wanted. The generals Santa Ana paid off with the cash were so offended by the deal, they overthrew Santa Anna again, and sent him into retirement for the sixth and final time.

James Gadsden had so exhausted himself offending the Mexicans, he died the day after Christmas, 1858, and so missed the start of the American Civil War. But when the south went into rebellion in 1861 the north was free to finally build the transcontinental railroad via the central route - which they finished in 1869. And when Gadsden's dream of the southern transcontinental would finally be built in 1881, it would profit the same western men who had built the original central route out of California - Collis Potter Huntington and Charles Crocker.

Crocker (above) was a 49'er from Indiana, who made his first fortune selling shovels to miners in Sacramento. Then he went into banking, and he was one of Big Four who formed the Central Pacific Railroad, the western end of the transcontinental. In fact "Charles Crocker and Company" was the prime contractor on the Central Pacific Railroad. Of course the shareholders in "Croker and Company" were the same men who owned the Southern Pacific. This is known as the "heads I win, tails you lose" school of finance. By 1877, the big Hoosier had so much money, he was running out of things to buy. And at that fortuitous moment, who should Croker meet but a slightly sleazy newspaper man named James Addison Reavis.

Reavis told Croker the story of the Peralta land grant. Of course he probably did not mention that the land grant was a myth. Probably. But Crocker and a few other select California investors were willing to fund more research into the claim. Did they ever believe in the validity of the grant? They would have smiled at that question, and regarded it as unimportant. The only thing that matters in the world of Capitalism, is what you can afford to prove in court. And James Reavis could now afford to research the heck out of the Peralta land grants. And this old forger figured he stood a pretty good chance of finding every single document he went looking for. In fact, he could guarantee it.

- 30 -

.jpg)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please share your reaction.