The apparitions rose from the fen so coated with mud they appeared to be the earth itself. It was a few minutes before 9:00 a.m. on Sunday, 17 May, 1863. The night chill was just melding into the heat of the day. The demoralized rebels, crouching behind cotton bales, had endured a demoralizing hour of heavy cannon fire methodically dismantling their fortifications from almost point blank range. And then, abruptly, a host of shouting banshees materialized almost on top of them, rising from the clinging mire, teeth and steel blazing in the sunlight. Reason evaporated. Logic dissolved. The rebels ran for their lives.

The Big Black River should have made a strong defensive position. The west bank was 60 feet above the meandering river and the swampy eastern shore. The railroad was carried 150 feet above the marshes and an oxbow lake on great stone supports, a bridge 1,250 feet long. Normally wagons and travelers on foot had to use a browbeaten ford, and then clamber up the steep slope. The 5 divisions of Lieutenant General John Clifford Pemberton's army of Mississippi could have easily held the west bank against Grant, at least for awhile. With a little stupidity on Grant's part, even the 3 divisions which had crossed Baker's Creek 2 days earlier might have resisted. But the broken parts of the army which had escaped the debacle at Champion Hill, stood no chance of stopping the victorious Yankee army less than 18 hours later on the eastern shore.

Instead of defending the west bank, Pemberton had posted a third of the battered remnants of his army with their backs to the river – just a day after the same sin had led to disaster at Champions Hill. Sent ahead late on the afternoon of Saturday,16 May the seemingly tireless Chief Engineer, Major Samuel Lockett, had conjured a defense across the boggy neck of the east bank of the Big Black river bend.

Cotton bales awaiting shipment at Bovina Station were brought by locomotive to the west bank and rolled down the shoulder of the railroad levee. Stacked several deep in a line across most the open face of the river bend they formed an instant fortification. With dirt thrown against them to dampen any sparks, it was the same defense which had worked so well at Fort Pemberton, in February.

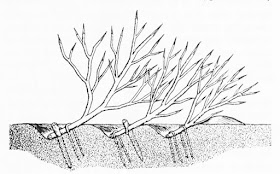

Then, in front of the main battle line, Lockett added a trick developed by the Roman Army 2,000 years earlier – abatis. These were tree branches driven into ground with their brittle arms facing the advancing Yankees. Like barbed wire a generation later, these abatis were intended to break up attacking formations.

Crossties were also brought forward from Bovina Station and dropped between the rails on the railroad bridge. Then dirt was scattered down, making it usable for horse drawn wagons.

But vividly aware of the disaster the day before, Lockett was determined to provide a second line of retreat. Close at hand was a small fleet of steamboats – the Dot, the Charm, the Paul Jones and the Bufort - which had plied the Big Black until the Yankees had captured Grand Gulf, at the river's mouth. Lockett had one of these, the Dot, brought south of the railroad bridge. Her engine was stripped and sent north on the river, and everything above her bottom deck was stripped off. Anchored to both shores, she formed a second bridge, for the men, if not their equipment.

Major General John Bowen's battered division filed into the new “fortifications” after midnight. Although they had suffered heavily at Champion Hill, they grew confident with the defenses they found awaiting them.

Brigadier General Francis Marion Cockrell's brigade was south of the road, and 47 year old Brigadier General Martin Edwin Green's brigade at the northern end of the line. Sandwiched between them were the 3 regiments of impressed draftees from east Tennessee, under General John Crawford Vaughn. Most of the rebels to the southern rebellion had already drifted away from their units by this time. But Pemberton had little faith in those who remained. And the weary Tennesseans who collapsed behind the cotton walls in the dark morning hours of Sunday, 17 May, knew their bodies were being offered as a sacrifice in the forlorn hope that Major General Loring's wayward division would soon arrive to rejoin the army.

As usual, Lieutenant General Ulysses Grant was prepared for this next step. His army was just as tired as the rebels. The only difference was that his men had won the day before. The Saturday night of 16 May, Grant let his men sleep where they were, atop the bloody hill. Alvin Hovey's 12th division was too damaged by the day's butchery to move the next morning. Better to allow them a day of rest, to recover those separated in the chaos, those confused or wounded or frightened, to find their way back to their units. Better to let them bury their own dead. They would follow the next day. But the rest of the army would not wait a moment longer than was necessary.

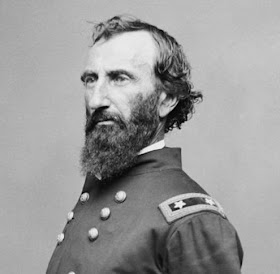

In the pitch black of 3:30 A.M., Major General Alexander McClernand (above) pushed his XIII corps west out of Edward's Depot. Brigadier General Eugene Carr's 14th division lead the way, with a skirmish line of Colonel Charles Lippicot's 33rd Illinois regiment sweeping both sides of the road ahead, collecting rebels who had collapsed and fallen asleep. Brigadier General Peter Joseph Osterhaus' 9th division was next in line, with Andrew Jackson Smith's 10th division bringing up the rear. James McPherson's entire XVII Corps would follow up the same road, but would not be required to form up until well after dawn.

William Tecumseh Sherman's (above) XV Corps – consisting of Frederick Steele's 1st division and James Tuttle's 3rd division - was just catching up with the army after occupying Jackson.

They had turned north at the town of Bolton, crossed Baker's Creek and were already marching west to reach the Big Black River 11 miles upstream at Bridgeport. Here Sherman expected to be rejoined by General Francis Blair's 2nd division, before crossing the river on a pontoon bridge he had been dragging along since Raymond. This crossing would outflank the entire Big Black River line, should Pemberton have decided to defend the west bank. Luckily for Grant, Pemberton had made it easy for him.

The Yankees were confident and careful. Examining the cotton bale defenses, General Carr spread his men out south of the Bovina Road. The Prussian immigrant Osterhause formed his division into a battle line north of the road and into the woods on his right. And like a carpenter choosing his his tools, Peter reached out the perfect weapon for the situation – the 10 pound Parrott rifle.

They were the largest field artillery piece used in the war. Being formed from brittle cast iron they were relatively inexpensive. Once drilled and rifled, water was poured down the barrel while a red hot cast iron band was clamped around the breech (above, rear). This reinforcement increased the muzzle velocity to over 1,100 feet per second, giving them an effective range of 3,500 yards – over a mile.

But the 20 pound Parrott had 2 disadvantages. First the gun and carriage weighed over 2 and ½ tons, requiring 8 horses to pull and 10 crew members to manhandle. And secondly, 22 of the big Parrotts were engaged during the Battle of Antietam the previous September, and 3 of them had blown out their breeches, killing many of their crews. This tendency of the brittle metal to fail caused more than a little unease among the crew of the 1st Battery of the Wisconsin Light Artillery, who had 6 of the behemoths in their care. But it was these guns that General Osterhause reached for on that Sunday morning, telling their commander, 25 year old Lieutenant Oscar F. Nutting, in his broken English, “I shows you a place where you gets a good chance at 'em”.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please share your reaction.