I think the 200 year old daguerreotype of John Clifford Pemberton (above) has influenced what historians think of the Vicksburg commander . To me, frankly, he looks a bit seedy. But in the flesh this 5 foot ten inch curly brown headed aristocrat was born with a silver stick up his butt and a marble chip on his shoulder. A few, a very few, were allowed to call him "Jack". With all others, he offered only cold reserve. To give our hero the most favorable interpretation, John Pemberton was the most famous American led to treason by his heart since Benedict Arnold. But there was a lot of that going around in 1860.

John Pemberton's family were wealthy Philadelphia Quakers, and the shallow youth inherited a brittle sense of entitlement. He was quick to take and deliver offense. He confessed to his mother, “I cannot always bear reproach though I deserve it,” and promised to do better. But he never did. While at West Point - from 1833 to 1837 - John became engaged to a Philadelphia girl. Then he met a more exciting paramour in New York City. The young lieutenant broke his engagement by mail. Shortly there after his new love buckled under family pressure and ended their affair. After that double fault John swore off serious women.

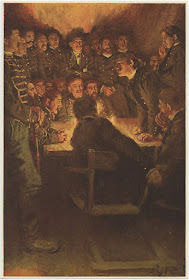

During John's antebellum West Point years, his best friend was William Whann Mackall (above), from a prominent Maryland slave owning family. Although trained as artillerymen, both cadets eventually became competent staff officers, dedicated to detail, minutia and the thousand little things that have to happen before a more empathetic field officer could inspire soldiers to fight. When asked to risk his own life, neither John nor William ever flinched. But John often charged to a trumpet only he could hear.

While stationed on the isolated Minnesota frontier, John's abrasive, self centered nature worsened, and he became a martinet, sparking conflicts with his fellow officers and inspiring one insulted corporal to take a shot at him. In 1842, while stationed at Fort Monroe, Virginia, the 34 year old Pemberton met his "Peggy Shippen". She was the 22 year old, 5 foot 2 inch tall Martha "Pattie" Thompson (above) . His wooing of the young lady was interrupted by the Mexican American War of 1846 - 1847.

His current enemy at Vicksburg, Federal General Ulysses Grant, described the Pemberton he served with under Major General Zachary Taylor. in northern Mexico this way; "A more conscientious, honorable man never lived," Grant generously wrote. "I remember when a (written) order was issued that none of the junior officers should be allowed horses during the marches...Young officers not accustomed to it soon...were found lagging behind." After a verbal order rescinded the restriction, all the other officers remounted, "Pemberton alone said, 'No,' he would walk," remembered Grant. And, "...he did walk, though suffering intensely... he was scrupulously particular in matters of honor and integrity."

When he returned to Virginia, brevet Major John C. Pemberton proposed to Martha. Her Episcopalian father, William Henry Thompson, was skeptical of the Quaker from Pennsylvania. He was a wealthy shipping magnate, dispatching vessels from Norfolk and Charleston to and from French ports.

And like most prosperous Virginians, the Thompsons defined their wealth in part by the number of their slaves. John's passion for Martha beguiled him into writing his own mother, "The more I see of slavery the better I think of it, " and he dismissed the victims as "lazy plantation Negroes". This disturbed John's anti-slavery Quaker family. But despite misgivings all around, the couple were married on 18 January, 1848 in Norfolk, Virginia and then moved to Philadelphia.

Marriage and fatherhood - 3 children over the next decade - did not mellow John. He argued with at lest one superior so often he was arrested for insubordination. When cooler heads prevailed, the charges were dropped. But it seems that Captain John Clifford Pemberton's career was saved only when slavery split the nation. John's parents pleaded with him to stay in the union. His older and younger brother both put on Union Blue. But Martha was drawn home to Virginia, and John followed her. Delaying his announcement until she and the children had reached Norfolk, John Clifford Pemberton then resigned his commission, and enlisted as a colonel in the Confederate Army.

Because of his father-in-law's prominence, in June of 1861 Confederate President Jefferson Davis made the Colonel a General, and put him in command of a brigade at Norfolk (above). His ruthless discipline produced immediate complaints, which did not stop until January of 1862 when he was promoted to Major General and assigned to defend Charleston, South Carolina. Which got him out of Norfolk.

Upon examining his new fiefdom, John dared to point out that Fort Sumter (above), the raison d'etre for the entire war, was obsolete and not worth repairing. The political outrage this produced was so fierce, that Pemberton's boss, General Robert Edward Lee, reprimanded him. Still, when Lee was transferred to Virginia, John was given command of all of South Carolina and Georgia. He was failing his way up the promotion lists.

This latest promotion didn't work, either. John offended too many people, too often. The complaints poured in. Eventually President Davis came up with what he thought was the perfect solution to his touchy, irritable argumentative northern southern officer. He promoted John again and put him in charge of defending Vicksburg. And that is why, after having failed at every job given him, John C. Pemberton rose from Colonel to Lieutenant General in 18 short months, without ever winning a battle or even hearing a shot fired in anger.

John's new command consisted of 54,000 men, but they were spread all across the state of Mississippi, as well as parts of Louisiana. There were 3 divisions - 21,000 men - on his left flank, at Vicksburg. There were about 19,000 men to defend his center, stretching from the state capital of Jackson, west along the delta rivers of the Tallahatchie and the Yazoo. There was also a token force of 1,400 on the Alabama border at Columbus. And finally, protecting his vulnerable underbelly to the south were the 12,500 men digging in at Port Hudson, Louisiana. Importantly, Pemberton's headquarters were in the state capital of Jackson, Mississippi , not at Vicksburg. John did not look at the Mississippi River every morning, judging its level, as Grant now did.

As a staff officer, John had solid rationalizations for remaining where he was. Jackson was centrally located. It had more secure road, rail and telegraph communications with Richmond. And when John and his staff first arrived, in October 1862, Grant's first advance into Mississippi was aimed ultimately at Jackson. But after Major General Earl van Dorn's December victory at Holly Springs, and the unwelcome appearance of General McClernand on the Mississippi, Grant was forced to shift his attack to the west. However Pemberton remained in Jackson.

Even after the attack at Chickashaw Bluffs. Even after the Desoto Canal. Even after the Lake Providence canal. Even after the Yazoo Pass was breached. Even after the battle of Fort Pemberton. Even after the threat of Steele's Bayou. Even after the Duckport Canal, which I have yet to recount. From October, November and December 1862 though January, February, March and April of 1863, Lieutenant General John C. Pemberton remained rooted in Jackson, mentally and physically, while the vital high ground, the the raison d'etre for his entire command, Vicksburg, was being wedged out of his control.

As proof, in mid April of 1863, when several Federal gunboats and transports ran past the guns at Vicksburg, John Pemberton, took far too long to realize the event had changed everything about the coming battle.

- 30 -

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please share your reaction.