I

invite you to watch as the brazen brown and yellow aircraft

designated “dash 80” slowly begins it's takeoff roll down runway

15/33. The four Pratt and Whitney turbojet engines, individually

suspended below the 35 degree sweptback wings, roar as they produce

44,000 pounds of thrust. At 120 miles per hour pilot Alvin “Tex”

Johnson firmly pulls back on the control column, and 200,000 pounds

of aluminum alloy, wires, rubber tubing and ambitions float off the

asphalt. It is 2:14 on Thursday afternoon of 15 July, 1954. The air

above Lake Seattle is populated with puffy white clouds. And as the

twin four-wheeled bogie tricycle gear of Dash 80 fold neatly into the

underbelly, the grounded Comet jet transport is about to become

obsolete. When he landed, 2 ½ hours later, “Tex” said, “She

flew like a bird. Only faster.”

Douglas

had dominated commercial aviation market since 1933, with their DC 3 (above) family of piston engine passenger planes.

Boeing survived

thanks to their military contracts - beginning with 17,000 B-17's built between 1935

and 1945.

This was followed by almost 4,000 B-29 SuperFortereses built between 1942 and 1945.

Then Boeing built 2,000 swept wing B-47 Strato-jets between 1948 and 1963.

Finally, beginning in 1951, Boeing supplied the U.S.A.F with 744 swept wing B-52

StratoFortress, still flying more than 60 years later.

So,

when Bill Allen, president of Boeing Aircraft Company, saw the de

Havilland Comet at the 1949 Farnborough Air Show (above), he was not

impressed. But what the Comet high lighted to the Boeing engineers

was that jet transports promised speed and reliability for anything

you could fit in the pressure hull.

The

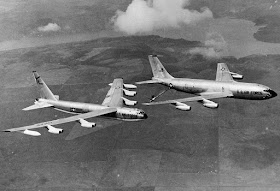

United States Army Air Corps had been experimenting with mid-air

refueling since 1927. Developments were slow, but by 1948 the USAF

had two squadrons of beefed up double body B-29's Tankers, which Boeing

initially called the 367s and which the U.S. Army relabeled the

B-50 (above)

The problem was the jet bombers could not comfortably fly slow enough without stalling to be serviced by these piston driven gas tanks. Also, at higher altitudes where the B-50's labored, the air was

“smoother”, making refueling easier. Obviously the Air Force was

going to need a jet powered tanker. And that was Boeing's initial

justification to nervous investors when, in 1952 Allen asked them to

risk 25% of Boeing's capital, some $16 million, to developing a jet tanker. But carrying fuel was only part of Boeing's idea.

Boeing

labeled their new aircraft Project 367-80. Eventually it became known

simply as the Dash 80. It was big - 128 feet long as opposed to the

93 foot long Comet – 130 foot wingspan to 115 feet for the Comet,

and a wing area of 2,400 square feet to 2,015 square feet for the

Comet. All that extra wing space, devoted entirely to fuel, gave the

Dash 80 a range of 3,530 miles to the Comet's 1,500.

The plane was so

big a passenger version was projected to carry at least 140 seats, five abreast,

compared to the Comet's 43 seats at two abreast, thus reducing the

operating cost to 25 cents per seat-mile for every gallon of kerosene

the four engines burned. Not to mention, the Dash 80 could cruise 100

mile per hour faster than the Comet. It looked like democracy with wings.

Boeing

swept the wings of the Dash 80 back to 35 degrees, which they knew

would be stable because that was the same angle as the wings on their

bombers. And they avoided new engine development by using the same

engines used in the bombers, and slung them beneath the wings for

easy maintenance, and to free up wing space for fuel, just like the

bombers. All of this would reduce the need to retool when and if the

various versions of the plane went into production.

Boeing

also learned from the well publicized crashes on Comet take

offs by designing forward and rear facing extensions (flaps, tabs, ailerons and

spoilers) on the swept wings of the Dash 80 (above). These allowed the big

bird to stay in the air at speeds as low as 80 miles per hour. To

allow passenger jet to use existing airfields of 7,000 feet,

clam shell thrust reversers were included, to slow the jet from the landing speed of 150 miles per hour to dead stop within 6,000 feet.

However,

the Dash 80 was neither a tanker nor a passenger plane. It was a test

bed for both. That did not matter, it seemed, because almost before

the 2 ½ hour maiden flight had landed, the Army ordered 29 of the

new, yet as un-built planes to be labeled the “K” (meaning

tanker) and “C” (meaning transport) -135 (above). Another 250 KC-135's

were quickly added to the order, the planes first reaching service in August of

1955.

The

airlines, however, showed little interest, in part because 1954 was a

recession year, but also because the disasters of the Comet were

still fresh in the public mind. Few seemed eager to risk their lives

on a passenger jet. So the Dash 80 flew on, amassing data to improve

the design.

Meanwhile, on Tuesday, 1 February, 1955, the the British Civil Aircraft Court of Inquiry

into the crashes of Comet Yoke Peter and Yoke Yoke was issued by the

Royal Aircraft Establishment. The fault, they had determined, was

“...metal fatigue, caused by the repeated pressurization and

de-pressurization exacerbated by the thin aluminum alloy skin...”

and the squared off windows which intensified pressures at the

corners.

De

Havilland responded with a public statement. "Now that

the danger of high level fatigue in pressure cabins has been

generally appreciated, de Havillands will take adequate measures...we propose to use thicker gauge materials...and to strengthen and redesign windows and cut outs and so

lower the general stress to a level...(which) will not constitute a danger.” The company

immediately began the work, but it would be 3 years before the

redesigned Comet 4 could re-enter commercial service.

It

was not until 2015, when the 50 years of silence required by the British government Secrets Act had expired that the

full truth of the Comet hull failures was revelled. Said the originally redacted

report, “...metal fatigue, attributed to raised stress at the

squared-off window corners, actually had another cause....the

structure had been designed to be bonded – glued, in fact –

by...the Redux process...”

However, “...During production...de

Havilland chief designer, R.E. Bishop (above)... decided that these areas

should...be reinforced...by normal aircraft riveting...It was this

'belt and braces' riveting...that caused the failures. The cracks

emanated from the rivet holes in the corner area – not from the

material in the corner structure itself.”

But

it was Tex Johnson (above), the Boeing test pilot, who drove the final nail in

the Comet coffin.

The stage was the annual Gold Cup hydroplane races

to be held on Saturday 6 August, 1955 - light high speed boats powered by air

craft engines, racing at 80 to 90 miles an hour across the surface of the water and throwing 30 foot

high rooster tails behind them. Viewed by perhaps 200,000 spectators

from the bluffs above Lake Washington, in 1955 for the first time the event was even

broadcast on live television.

That

same week, The International Air Transport Association and the

Society of Aeronautical Engineers were both holding their conventions in

Seattle. So Bill Allen invited a large number of aviation industry

folks to attend the races, and had coordinated with the Dash – 80

team to do a fly by. That was all Tex Johnson was supposed to do -

fly by.

But

Tex had heard that Douglas aircraft, which had started a crash

program to build their own slighter smaller and slightly slower jet passenger plane, the DC 8 (above),

was telling potential customers that the Boeing jet was unstable.

Tex (above left) felt obliged to prove the critics wrong. As the Dash 80 was in route

to Lake Washington, he told his co—pilot Jim Gannet (above, right) , “Hey Jim,

I'm going to roll this airplane over the Gold Cup." Gannet

suggested if he did, Jim Allen would fire him.

Johnson

then steered the big jet down to 500 feet for the fly-by east bound.

And as he passed the spectators, Tex pulled up slightly and slipped

the aircraft into a gentle roll to the right, 360 degrees - a perfect barrel roll. (Barrel Roll). It was perfectly safe, according to “Tex”. “The airplane does not recognize attitude,” he later explained, “providing a maneuver is conducted at one G...The barrel roll is a one G maneuver and quite impressive, but the airplane never knows it’s inverted.”

The

gamble worked. Less than 2 months later, on 13 October, 1955, Pan

American World Airlines ordered 20 of the newly designated Boeing 707

jets, to replace their cancelled Comet orders.

The only fly in the ointment

landed when Douglas upgraded the engines on their DC-8's, forcing

Boeing to follow suit. That delay prevented the first 707 commercial

flight until October of 1958. But by 1956 even British Overseas

Airway Corporation had ordered Boeing's big jet. Until the production

lines shut down in 1978, Boeing built 865 of the big 707 airplanes.

The

British government remained loyal to the de Havilland Comet, and in

March of 1955 British Overseas Aviation Corporation ordered 19 of the

new Comet 4's (above). To extend its range, the Comet 4 had a fuel tank pod perched in each wing, and the wings themselves were bigger, as were the

engines.

On 4 October, 1958 it was a Comet 4 that flew the first jet

London to New York flight, with a westbound refueling stop at Gander,

Newfoundland. But the new Comets could only squeeze 99 passengers

into the larger pressure cabin, and de Havilland's plane was still 50 miles

per hour slower than either the Boeing 707 or the DC-8. De Havilland

sold only some 76 Comets, before production was stopped in 1964.

In

1960 de Havilland was acquired by Hawker Siddeley in a government

brokered sale and the name de Havilland faded from British aviation.

The Canadian government bought the subsidiary de Havilland Canada,

and for the next 20 years produced a successful line of short take

off and landing civilian aircraft. But in 1984 the conservative

government of Brian Mulroney privatized the company, and in 1986 de

Havilland Canada was bought by Boeing. Despite promises to Canada, Boeing closed the plant and

broke up the jigs and all production equipment, and that really was the end of de Havilland.

Today, (2020) Boeing itself is reeling from their own self-engineered 737 Super Max debacle - 2 crashes and 346 dead, caused by a preventable failure - followed by the COVID 19 pandemic which gutted air travel for an entire year.

Boeing in 2020 seems to be facing a similar

fate to the one de Havilland faced in 1954, building airplanes nobody wants to fly aboard.

As one of the Farnborough

engineers pointed out back in 1954, ‘There

are rarely new accidents, just old accidents waiting for new people

to have them.”

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please share your reaction.