I don't always believe the Roman historian Plutarch. Still, Plutarch always told a good story. His tale of the death of Pompey the Great is a perfect example. According to Plutarch, after losing at Pharsalus, Pompey sought refuge in Egypt, expecting support from the son of an old debter of his, fourteen year old Theos Philopator, Pharaoh of Egypt, also known as Ptolemy 13 – interesting number, don't you think? You see, Ptolemy 13 was in Pelusium, the silt plagued port and fortress at the eastern edge of the Nile delta, because he was avoiding his two sisters, both of whom were trying to kill him. It was a great confused mess, and a very bad time to arrive in Egypt seeking help. But then Pompey's timing had never been very good.

Pompey's arrival on 29 September, 48 B.C.E., presented Ptolemy 13's advisors with a bit of a conundrum. If they helped Pompey they would anger Julius Caesar, who had just defeated Pompey's army at Pharsalus. It they sent Pompey packing and he later won his civil war with Caesar, Pompey would make sure bad things happened to Ptolemy 13 and his advisers. However, there was a simple solution to this problem, and I am surprised it never occurred to Pompey. It certainly occurred to Ptolemy 13's advisers.

They sent a boat out to Pompey's ships, which were anchored just outside the harbor of Pelesium. A Roman centurion named Septimius, who had been sent to Egypt by Pompey to reinstate Ptolemy 12, Ptolemy 13's father, was in that boat. He assured his old commander that it was safe to come ashore.

Pompey climbed down into the boat. As they approached the shore, Pompey could see Ptolemy 13 in his sedan chair, waiting on the beach. But something did not seem right, and Pompey hesitated. Then

one of Ptolemy's generals, a half Greek named Achilles, called out that the Pharaoh was very busy but could give Pompey a few minutes of his time, right now. It still smelled fishy, but Pompey really had very little choice. His crews and his family needed water, and food, and somebody who knew the coastline down to Tunisia, where he had more legions and allies...So the old fool got in the boat..

Pompey climbed down into the boat. As they approached the shore, Pompey could see Ptolemy 13 in his sedan chair, waiting on the beach. But something did not seem right, and Pompey hesitated. Then

one of Ptolemy's generals, a half Greek named Achilles, called out that the Pharaoh was very busy but could give Pompey a few minutes of his time, right now. It still smelled fishy, but Pompey really had very little choice. His crews and his family needed water, and food, and somebody who knew the coastline down to Tunisia, where he had more legions and allies...So the old fool got in the boat..

He never made it to shore alive. According to Plutarch, as the boat passed the breakwater, Pompey was rehearsing his Greek greetings for the Ptolemy 13, when Septimius stabbed him in the back. They dragged the boat ashore and then dragged the wounded Pompey up on the sand. There they chopped off his head It was a cold and heartless thing to do, particularly since Pompey's wife was watching from the galley off shore. But it wasn't anything Pompey hadn't done to countless others. And that was the death of Pompey the Great, one of the most overrated generals in history, a man whose greatest sin was in believing his own press releases, which he had written.

That was one problem solved, leaving Ptolemy 13's advisers with their original problem, his sisters - in particular his elder sister and her hired army. She was hovering out in the Sinai desert, short of food, water and money to pay her soldiers. It looked as if she was about to be easily be crushed by Ptolemy 13's army when, just two days later- 1 October, 48 B.C. - yet another Roman annoyance arrived off shore. This time it was Julius Caesar (above), with a Roman legion. Dutifully, the advisers of Ptolemy 13 sent a boat out to Caesar, carrying the head of Pompey. But if Ptolemy 13's advisers expected Caesar to thank them for eliminating his enemy and sail off back to Rome, leaving them free to finish off their business without further distraction, they were sadly mistaken. Oh, Caesar did sail off from Pelusium. He just didn't didn't sail for Rome. A few days later Cesar landed in Alexandria and took over the empty royal palace.

I honestly don't know if Caesar really cried when he saw Pompey's head. He said he did. But Caesar must have known the instant he looked into those foggy dead eyes that he had won his civil war. There was more fighting to be done, of course. He would have to move on to Tunisia, to finish off Pompey's troops there. But there was no longer any need to rush. With Pompey dead the Senate aristocrats had lost their champion and rallying point. Caesar could allow their army in Tunisia to wither on the vine a little, while he took advantage of an opportunity right here in Egypt. Ptolemy's army at Pelusium might be blocking his sister's army from entering Egypt, but Caesar's 5,500 man force in Alexandria was sitting on the Egyptian treasury, the gold used to pay Ptolemy 13's soldiers. To paraphrase an American Vietnam War general, grab them by their ingots and their hearts and minds will follow. Caesar now summoned both Ptolemy 13 and his sisters to Alexandria to settle their civil war. And to be honest with you, I don't think Caesar particularly cared which ones, if any of them, showed up.

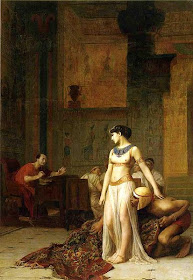

It turned out they all did - Ptolemy 13 and his two sisters, Asinoe 4, and Cleopatra 7. Ptolemy 13 had the easier time getting to the Alexandria, but even Cleo made it, and she first had to slip around her brother's army and be smuggled into the palace in a rolled up carpet - if you believe Plutarch. But once she was there, Caesar was required to protect her since he had summoned her. And as Caesar was a heterosexual, he quickly fell under the spell of this extraordinary young woman.

The advisers of Ptolemy 13 saw which way the perfumed wind was blowing, and they did not like it.

They formed a secret alliance with Cleopatra's younger sister, Asinoe 4. She slipped out of Alexandria and hurried to join Ptolemy 13's army at Pelusium. But, once there she started calling herself Pharaoh, and when the commander of the Army, General Achilles, the man who had helped trick Pompey to his death, protested her use of the title, she had him killed. Well, turn about is fair play, isn't it? The army did not approve of the lady's ego trip, and offered her in trade for Ptolemy 13. For some reason Caesar accepted the deal, probably because Ptolemy 13 swore he would surrender his army to Caesar. But once back with his army, Ptolemy 13 and his advisers chose to lay siege to Cesar in Alexandria in December of 48 B.C..

Caesar was trapped in the city, with just one legion, and that was not enough. But he had already called for reinforcements, and when they arrived in early January of 47 B.C. they smashed Ptolemy 13's army. On 13 January the fifteen year old Ptolemy 13 was drowned in the Nile, maybe by accident and maybe by a bribed Egyptian. But however the boy died, Cleopatra 7 was now the Pharaoh in Egypt. Caesar had Asinoe 4 placed under arrest, probably to protect her from Cleopatra – the lady had an understandably heightened sense of self preservation.

Just 8 months after Cleopatra 7 first rolled out of a carpet at the feet of Julius Caesar, on 23 June, 47 BC, she gave birth to a son. It was observed that as the boy, Ceasarian, grew, the more he resembled Caesar. He was one of two males who may have been Caesar's sons. The other was the child of Caesar's widowed girlfriend, Servilla. That boy, whom Caesar never officially adopted, was Marcus Junius Brutus.

- 30 -

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please share your reaction.