At

about 10:00 a.m. on Friday, 3 July, 1863, a pair of rebel officers

walked 100 yards to the Yankee trenches. Once inside they were

introduced to the short and feisty commander of the 10th

division, XIII Corps, 48 year old regular army General Andrew

Jackson Smith. (above).

The junior Confederate, Colonel L.M. Montgomery, carried a letter from Lieutenant General John Crawford Pemberton, which read, “I

have the honor to propose an armistice...with the view to arranging

terms for the capitulation of Vicksburg. To this end, if agreeable to

you, I will appoint three commissioners, to meet a like number to be

named by yourself, at such place and hour today as you may find

convenient. I make this proposition to save the further effusion of

blood, which must otherwise be shed to a frightful extent, feeling

myself fully able to maintain my position for a yet indefinite

period....”

The

letter went from General Smith to Major General James McPherson, and

was read by those officers and discussed with their staffs. By the

time it had reached Grant, the contents were common knowledge among

staff officers, as was the identity of the second rebel officer, 32

year old Major General John Stevens Bowen (above). He had been promoted to

Major General after the Federal noose had cut Vicksburg off from the

outside world, so the Confederate Congress was unaware of Pemberton's

largess toward the man who had forced the court martial of General

Van Dorn – Pemberton's predecessor. Bad feelings in Richmond might

delay approval of Bowen's promotion. Still, few would have questioned

his qualifications as displayed at Shiloh and Cornith and Champion's

Hill.

Like

Grant, John Bowen (above, antebellum) had graduated West Point. And like Grant, he had

been posted to the Jefferson barracks in St. Louis. Both men had

married into prominent Missouri families. Transferred to duty in the

west, both men were so miserable they resigned from the army. But

Grant had then been forced to try his hand at farming, while Bowen

could fall back on a family fortune. Bowen became an architect, and

returned to St. Louis in the 1850's to open a successful firm with

Charles Miller. When Grant was reduced to selling firewood on the

street, the firm of Bowen and Miller bought their firewood from

Grant. It was not a relationship designed to encourage camaraderie.

Grant's (above) reply to Pemberton reversed the path of the appeal, and was just as

widely known. “Your note of this date is just received, proposing

an armistice...The useless effusion of blood you propose...can be

ended at any time you may choose, by the unconditional surrender of

the city and garrison...I have no terms other than those...”

In

retrospect Pemberton's note seemed to invite the repetition of

Grant's terms from 16 February, 1862, at Fort Donaldson (above), “No terms

except an unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted. I

propose to move immediately upon your works”. Once again Ulysses S.

Grant would become

“Unconditional Surrender Grant" in the press. But Bowen, reading

the response while still in the Yankee trenches decided he could not

wait for gentlemanly formalities.

Bowen

appealed directly to General Smith, requesting that he ask

Grant if he would not at least meet with Pemberton in person, today.

After a few moments wait a runner returned with Grant's agreement to

meet between the lines in front of General McPherson's Corps, at a

time of Pemberton's choosing. And then the pair of Confederates

carried their rejected truce flag back to the Confederate lines.

Grant's

harsh terms set off an animated discussion in Pemberton's

headquarters (above) . Honor insisted the rebels chose to fight rather than

humiliation. It was insane, of course. There were already 10,000 men

on rebel sick lists - 1/3rd of the army too disabled by diarrhea, disease and

wounds to participate in a march let alone an attack to reach

Johnston's Army of Relief. Then Bowen announced, “General Grant

would like to negotiate this afternoon with General Pemberton.”

Grant,

of course, had suggested no such thing. Bowen had suggested the

meeting. But other than a momentary wonder that Bowen had waited to

mention this, the Confederates were greatly relieved. What else

could they think except that Grant's written demand was a mere

publicity stunt and there was to be the very negotiations which

Pemberton had offered in his note. Pemberton (above) quickly sent word

through the Yankee lines that he and his negotiators would meet with

Grant and his, at 3:00 p.m.

But

why had Bowen waited to announce Grant's acceptance of a meeting? And why had he created

the impression that Grant sought negotiations? Bowen knew that with

Johnston's army at the Big Black River, Grant was motivated to drop his demand for unconditional surrender - as he

had at Fort Donaldson. Bowen also knew that most rebels paroled

from Vicksburg could re-enter the fight – as they would do at

Atlanta in 1864. But in trying to manipulate Grant and Pemberton into a

quicker resolution, the risk was that when Bowen's ruse was

discovered, as it must be, both men would feel cheated, and their

anger could result in a slaughter. Why was Bowen running such a risk?

Like

every one inside Vicksburg, Bowen was exhausted and near a physical

and emotional collapse. Suffering already from the malady which would

soon kill him, Bowen may have felt he had not the strength to wait

for the slow witted Pemberton to face reality, or for Grant to accept

the victory he was being offered, instead of the one he wanted. Bowen

may have felt the situation had to be forced. Or he may just been a

tired sick man, slowly losing control of his mind and body.

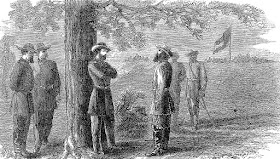

They

met at 3:00 p.m near a tree near the rebel trenches (above). Pemberton, ever

the gentleman, began by seeking to make Grant's come-down as easy as

possible. He said he understood the Yankee had asked for this

personal interview. Surprised, Grant honestly answered that he had

not. Shaken, but determined, Pemberton then asked what other terms

might Grant be willing to offer. Grant replied there were none. And

for a moment Pemberton stood silent, feeling as if he had

been slapped on the face. Ever the gentleman, he now said stiffly,

“Then, sir, it is unnecessary that you and I should hold any

further conversation; we will go to fighting again at once.”

And

it was now, according to Grant, that John Bowen stepped forward. He

began by saying he was anxious that the surrender be consummated

right here, and now. He suggested that he and Yankee General Andrew

Smith negotiate between themselves. In Pemberton's version, he was

the one who made the suggestion. But it is unlikely anybody sat and talked.

In any case, while Grant (above) and

Pemberton small talked about the Mexican War, Smith and Bowen agreed

to a cease fire until final terms were decided. Then Bowen suggested

Vicksburg would surrender while the Army of Mississippi would simply

leave. Presumably Grant would believe they presented no threat

because of their physical condition. Grant killed that idea out

right. The General from Galena was now so frustrated he ended the

meeting. He accepted the cease fire, and said he would counter

Bowen's offer by 10:00 p.m. that night.

It

must have been an interesting evening meal in Pemberton's

headquarters. The food, what there was of it, was at least warm. Maybe John Pemberton was too ill to accuse Bowen of duplicity. But

the emotional roller coaster day of that had left them all exhausted. The Gentlemen

from the south must have known, no matter what terms Grant offered,

they had little choice but to accept them.

Grant

must have been struggling with his temper. He'd been lied to. But

once he got over that anger, as usual, he saw the situation with clarity. At 10:00 p.m. a white flag appeared over the Smith's trench

line, heralding a letter addressed to Pemberton – not Bowen. It was

a not a negotiation, but a statement of intent.

“ I will march in

one division as a guard and take possession at 8 A.M. tomorrow. As

soon as paroles can be made out and signed by the officers and men,

you will be allowed to march out of our lines, the officers taking

with them their regimental clothing, and Staff, Field and cavalry

officers one horse each. The rank and file will be allowed all their

clothing, but no other property...any amount of rations you may deem

necessary can be taken from the stores you now have...You will be

allowed to transport such articles as cannot be carried along. The

same conditions will be allowed to all sick and wounded officers and

privates as fast as they become able to travel...”

At

dawn on Saturday, 4 July, 1863, Pemberton sent his reply. He sought 2

small face saving addendum. First, his men would stack their own arms and

colors in front of their current positions, and second they would evacuate their trenches at 10:00 a.m. without turning them over to the Yankees. Since Grant voiced no objections, that was the way it would be done.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please share your reaction.