I suppose there are a hundred measures by which to assess the history of Phineas P. Gage. The most unlikely might be the field of phrenology, which held that just as a lifetime of muscular exertion leaves evidence on the leg and arm bones, mental endeavors - personality, intelligence and emotions - leave tell-tale imprints on the top of the skull: or so the theory went.

Practitioners, like the American Orsen Squire Fowler (above), would run their fingers over the bumps on your head and divine your occupation, your character flaws, even why you were having trouble sleeping.

But as profitable as the business was, even Fowler acknowledged, "....phrenology is either fundamentally true or else untrue..." - a statement which, standing alone, is undoubtedly true. The ultimate disproof of phrenology would be provided by the words Pheneas P. Gage.Phineas was originally an Egyptian title, meaning a dark or bronze skinned oracle. He first appears in the Old Testament (Numbers 25, verses 7-8), as a priest's son who spies the Hebrew prince Zimri entering the Tabernacle with a Midianite woman. In a fit of offended religious passion, Phineas runs them both through with a spear. For this double murder, Moses rewards Phineas. His namesake may have paid the price for that excess of zeal.

His family name was English, which actually means it came from the French spoken in Normandy in 1066. This Old French was mostly based on the everyday language spoken by Roman soldiers. In their Vulgate Latin a "jalle" was a measure of liquid, equal to our gallon, and a "jalgium" was the stick or rod inserted into the amphora to measure how much wine was left. Over centuries the pronunciation became a "gaunger" later shortened to "gauge". Thus a gauge is a standard of measurement. And by a happy coincidence, that describes Phineas Gage perfectly - an oracle of measurement.

In 1823 Phineas P. Gage was born in the southern New Hampshire village of Lebanon. He grew into a strikingly handsome young man, and a natural leader. The doctor for the Burlington and Rutland Railroad, physician John Martlyn Harlow, described Phineas as "...a perfectly healthy, strong active young man, 25 years of age...5 feet 6 inches tall...150 pounds...having had scarcely a day's illness...."

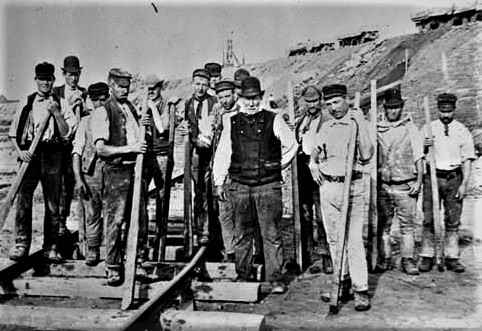

Navies were members of the work teams - inland navigators - who laid out the path of railroads crossing the land. The weak steam engines of the day could climb or descend no more than a 1 1/2 % grade, or rise 18 inches for every foot forward. Any obstacles to this would have to be blasted out of the way. But it was worth the effort because of the money that could be made from transporting resources by rail.

In 1825 Englishman George Stephenson's locomotive "The Rocket" (above) took less than two hours to haul 36 wagons of loaded with coal, nine miles from the mine to the docks on the River Tees. His steam locomotive was not only a revolution in speed, but also reduced transportation costs by two thirds.

Competitors literally followed in Stephenson's tracks. George had set his new rails four feet eight and one-half inches apart because that was the "gauge" of the old rails used when the wagons were pulled by horses. And by decree of the royal commission of 1845, that would be the "Standard Gauge" for Britain, and eventually most of the rest of the world.

Just three years later, on Wednesday, 13 September, 1848 a Rutland and Burlington Railroad construction crew, headed by the 25 year-old foreman Phineas P. Gage, was preparing a road bed outside of the little mill town of Cavendish, Vermont. Each member had a simple job, which is to say their collective task was a technically complicated jigsaw puzzle of mundane occupations, which when combined in a specific order, changed the world.

In this case, an engineer would determine where rock was to be removed. Team members would then pound a drill into the rock, creating a hole. As foreman, Phineas Gage would then pour a measure of black powder into the hole. Then he would pour a measure of sand on top of the powder. Then Phineas would insert a fuse through the sand and into the powder.

Then he would drop a 35 pound, three and a-half foot long iron tamping rod (above), sharpened at one end, into the hole to compact the charge and sand. Finally, Phineas would light the fuse.

After the resulting explosion (above), other workers with shovels and carts would remove the broken rock while the foreman engineer would determine where the next charge should be placed.

Toward the end of a had day's work, the team had just about finished clearing a curved cut through a granite outcrop (above). At just about 4:30pm, Phineas ordered his weary drilling team to take cover yet again.

Again Phineas poured black powder into the drill hole. But this time, in his haste or wearyness, he forgot to add enough sand. So when he shoved down the iron tamping rod down the hole, it sparked against the granite. And without the insulating sand, that set off the black powder.

In something less than one second, the 35 pound rod was driven out of the hole, penetrating just below Gage's left cheek bone, destroying his left eye, plowing through his brain and blasting out the top of his skull.

The tamping rod landed 80 feet away, smeared in blood and brain matter..

As the smoke cleared, the startled crew rushed to Phineas' assistance. They found him awake and alert, but in great pain.

With assistance Phineas was loaded aboard an ox cart, and suffered a jarring forty-five minute long, three quarters of a mile ride back to the Adams Hotel in Cavendish. During the ride Phineas called for his work book and made notes concerning the days progress. Once back at the hotel, Phineas was was placed in a chair on the front porch.

An hour local doctor, Edward Williams, arrived. "I first noticed the wound," wrote the good doctor, "before I alighted from my carriage, the pulsations of the brain being very distinct." The doctor recorded that his patient had a pulse of 60, was breathing regularly and his pupils were reactive. He reported no pain. "Mr. Gage...was relating the manner in which he was injured to the bystanders," wrote Dr. Williams, ".(and then) got up and vomited; the effort...pressed out about half a teacup full of the brain, which fell upon the floor."

The tamping rod had performed a frontal lobotomy on Phineas Gage's brain, disconnecting that part of his mind which dealt with "....future consequences... chooses between good and bad actions... (and) override(s) and suppress unacceptable social responses..." (Wikapedia - "Frontal Lobe").

Severing the neural connections with the frontal lobe causes patients to "...not respond to imaginary situations, rules, or plans for the future..." and who tend to be "...unusually aggressive ". And in the case of Phineas Gage, he tended to ".. use puns a lot." In other words, Phineas Gage was a new gauge of the human brain.

About 6:00 pm a company doctor, John Martyn Harlow (above) arrived and took over treatment of the unusual young patient.

To no one's surprise, the company doctor decided the young man with the hole in his head could be quickly released from care. And despite several setbacks, Dr. Harlow deemed Phineas able to travel the thirty miles to his mother's home, in Lebanon, New Hampshire for Christmas in 1848.

He returned to Cavendish in April of 1849, and Dr. John Harlow noted "his physical health is good, and I am inclined to say he has recovered. Has no pain in (his) head, but says it has a queer feeling which he is not able to describe."

Phineas never worked as a "navvie" again. Briefly he tried selling his story via public speaking engagements, and displaying the very rod (above) which had passed through his brain.

But handsome though he still was, that career never suited him. Despite rumors that he appeared in P.T. Barnum's museum in New York, there is no evidence he ever did. Instead, in 1851, he found a job at the Hannover Inn in Dartmouth, New Hampshire, as a stable hand and coach driver. Perhaps he found animals a better gauge of Gage than humans.

Then in 1854 he moved to driving for another stage line , this time in Valparaiso, Chile (above). He took with him his "constant companion", that iron tamping rod.

Phineas held down his new job for seven years, driving the 70 miles up and down the steep mountain roads (above) between Valparaiso, and Santiago. That would seem to me to be a far longer than you would expect from an unpredictable violent man, as Phineas was described in later medical texts. But I suspect those are just inventions based on old wives' tales. But one of the occasional side effects of a frontal lobotomy are seizures caused by scar tissue within the brain. And those now began to plague Phineas.

In 1859 Phineas rejoined his mother, sister and her husband, who were now living in California. He got a job as a farm hand in Santa Clara County (above), at the southern end of San Francisco Bay. But the seizures got worse, and on 21 May, 1860, Phineas Gauge died of what the doctors called complications of epilepsy, six months short of twelve years after he forgot to load enough sand atop the black powder.

Phineas Gage died just as the American Civil War was exploding. Over the next four years the number of survivors with similar brain injuries multiplied.

Doctors now had patients and skulls aplenty to examine, and upon reflection they reached several conclusions. First, it was clear that the bumps on the top of the head had no connection to anything going on inside the skull. Phrenology was bunk. But the disabilities of various head wound survivors (above) was proof that different sections of the brain did perform different functions.

And third, the old adage that medicine is the search for profit after death, was confirmed when in 1866, the ex-company Doctor John Harlow convinced (paid?) Phineas' sister and brother-in-law to disinter Phineas just long enough to chop off his head and ship the skull and the infamous tamping rod back to Boston.

There Doctor Harlow used the skull as an exhibit in his second (and more colorful) paper on his most famous patient. It was this paper which enlarged on the stories of his post accident temper and use of profanities. But there can also be no doubt that even after his death Phineas reset the gauge for our understanding of brain injuries.

A 2012 study by Harvard University determined the iron rode had "...destroyed approximately 11% of the white matter in Gage's frontal lobe and 4% of his cerebral cortex". However, this study did our hero no good whatsoever. The story of Phineas P. Gage can thus serve as a parable of the dangers in being in the forefront of medical science.

- 30 -

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please share your reaction.