A young white woman living through the siege recorded 25 June, 1863, as her worst day. “We were all in the cellar,” she recalled, “when a shell came tearing through the roof, burst upstairs, tore up that room, and the pieces coming through both floors down into the cellar.” A fragment tore her husband's 'pantaloons', proof that the cellar did not offer absolute protection.

Then a neighbor arrived to inform the shaken couple that a female friend had her thigh crushed by a Yankee shell. And shortly thereafter the owner's black slave girl returned from an errand for milk with the report she had seen the arm of another young slave girl taken off by another Yankee shell. Wrote the young woman of Vicksburg, “For the first time I quailed.”

She added, “I do not think people who are physically brave deserve much credit for it; it is a matter of nerves. In this way I am constitutionally brave...But now I first seemed to realize that something worse than death might come; I might be crippled...Life, without all one’s powers and limbs, was a thought that broke down my courage.” She pleaded with her husband, “I cannot stay. I know I shall be crippled.” And yet, she stayed.

At about 1:30 p.m., on Wednesday, 1 July, 1863, a second Yankee mine of 1,800 pounds of black powder was ignited under what was left of the Louisiana Redan. Wrote a southern witness, “The entire left face, part of the right, and the entire... (center) of the redan were blown up...” The chasm left behind was 20 feet deep and 30 to 50 feet across. The 3rd Louisiana lost another 1 killed and 21 wounded. But the 6th Missouri, which had replaced the Louisiana soldiers inside the remnants of the redan, lost about 90 men, killed and wounded.

Corporal Gilbert Stark, Company B, 32nd Ohio Volunteer Infantry noted in his diary, “The explosion was not so loud as before, but it was more effective. It blew 4 rebs clear over to our lines. 2 were dead, 1 was badly wounded. The other I don't think is hurt much. It must of blew lots of the rebs to hell…” But as the dust settled, curiously, “Our men did not advance...”

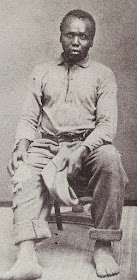

There had been 8 slaves forced to dig a counter mine under the redan, overseen by a white corporal. When the mine was ignited the corporal was killed as were 7 of the 8 slaves. The man who survived was identified only as Abraham (above) . Thrown 150 feet, he landed among Yankee soldiers. Surgeon Silas Thompson Trowbridge, from Decatur, Illinois, found Abraham was “Badly bruised”, but noted he had fallen “on soft ground, and evidently on the back part of his head and shoulders...” Shortly thereafter, as he lay in a tent to recover, the soldiers charged admission just to look at him. There is no record of how he handled the psychological impact of his survival. But later he was hired as a kitchen assistant for a Yankee general. Or so the story went.

A story was told that late in the siege of Vicksburg a white male broke down in public. With tears streaming down his face he began to sob, and through paroxysms of exhaustion and fear and grief he pleaded, “I wish they would stop fighting, or surrender or something, I want to go home and see my Ma.” One of the hardened soldiers of the 3rd Mississippi responded by mocking the man, and quickly the lament began to move north and south along the trench line - “Boo hoo. I want to go home.” It became the soldier's mantra, and never failed to produce smiles. “Boo hoo. I want to go home.” Or so the story was told.

There was no attempt to advance after the second explosion, in part because the redan no longer existed, and in part because the situation no longer demanded such sacrifice. On Monday, 30 June, Grant's engineers had reported there were now 13 mines ready or almost ready to be ignited under rebel works. Instead, Yankee infantry were ordered to broaden the trench approaches to the mined forts, so that the Federal troops could charge 4 abreast into their ruins. Tentatively, Grant set the ignitions and final mass attack for Sunday, 5 or Monday, 6 July.

That Wednesday, after the elimination of the Louisiana redan, Lieutenant General John Pemberton (above) sent a confidential message to his division commanders, Major Generals Carter Stevenson, John Forney, Martin Smith and John Bowen, asking them to immediately poll their general officers. “Unless the siege of Vicksburg is raised, or supplies are thrown in,” he wrote, “it will become necessary very shortly to evacuate the place....You are, therefore, requested to inform me with as little delay as possible, as to the condition of your troops and their ability to make the marches and undergo the fatigues necessary to accomplish a successful evacuation.”

On Thursday, 2 July, the Vicksburg Wig published one of their famous wallpaper editions, in which they recorded the death of a Mrs. Cisco, who while traveling on the Jackson Road had been struck by Yankee shell and killed instantly. According to the paper, her husband was a member of “Moody's Artillery” - aka the Madison Louisiana Light Artillery – on service in Virginia. All told, about a dozen civilians were killed by the 16,000 Yankee shells thrown at Vicksburg. But they included a young girl, enjoying a moment of freedom from her families' cave, who was struck in the side by a piece of shrapnel, and a young boy whose arm was “struck and broken” while playing outside of his cave.

Typical of the responses to Pemberton's query, was that from Brigadier General Louis Herbert, (above) in Forney's division, who canvased his own regimental commanders. “Without exception”, he now told his bosses, “all concurred...that their men could not fight and march 10 miles in one day; that even without being harassed by the enemy...they could not expect their men to march 15 miles the first day; hundreds would break down or straggle off even before the first lines of the enemy were fairly passed. This inability on the part of the soldiers does not arise from want of spirit, or courage, or willingness to fight, but from real physical disability... the question...is not between " surrender" and "cutting out;" it is are my men able to "cut out." My answer is No!”

But General Herbert did not stop there. “So long as they are fighting for Vicksburg,” he told Forney, “they are as true soldiers as the army has, but they will certainly leave us so soon as we leave Vicksburg. If caught without arms by the enemy, they will be no worse off than other prisoners of war...If they succeed in getting home, they will not be brought back to the army for months, and many not at all...I could not expect to keep together one-tenth of my men a distance of 10 miles.” This discouraging note was signed, “sincerely yours, Louis Hebert, Brigadier-General.”

None of the general officers urged Pemberton to hold out. Two bluntly stated that the army should be surrendered at once. Typically, Pemberton responded to the pressure by calling for a council of war, delaying the decision until his general officers again discussed what was already an almost unanimous opinion. According to Pemberton's engineer – Alabama's Major Samuel Henry Lockett (above) – they had been short ammunition from the beginning of the siege, they were short provisions, no man had been off duty for longer than “a small part of each day”, their lines were badly battered, many of their cannon were dismounted, and the Yankees had pushed their saps so close that “a single dash could have precipitated them upon us in overwhelming numbers”.

Pemberton then admitted that he had given up all hope for General Johnston's Army of Relief. The choice then was to “either to surrender while we still had ammunition enough to demand terms, or to sell our lives as dearly as possible” in a breakout attempt. He then asked for a final vote. All but 2 of his officers voted for an immediate surrender.

At 10:00 a.m. on Friday, 3 July, 1863, white flags appeared above a length of the Confederate trenches. Slowly the steady, killing gun fire along that section of the battle lines, ceased. And then two officers in gray began walking toward the Union lines, carrying a white flag.