I heard about a guy who came up with a brilliant idea and made a billion dollars. He built himself a huge mansion (above) and lived happily ever after. It happens. Of course you never hear about the fifty or sixty guys who came up with exactly the same idea and then went broke. The text books call this capitalism. I call it the “Savannah Effect”, that being the name of the first ship to cross the Atlantic Ocean between America and Europe using steam power.

It happened in 1819 and if you check the history books you will discover that the first steam ship to cross the Atlantic was the “Great Western” (above) or the “Cape Breton” in 1833, or the “Siruis” in 1838. But you will rarely hear about the “Savannah” because that innovative ship never made a dime. And in a capitalist culture this is the big secret, I mean besides the secret that advertising lies. Failure is the other big secret.

The alternative energy folks are now selling the idea that sailing ships can cross the ocean powered by the free fuel of the wind: except the wind is not free. It requires masts and sails and a lot of rope and it once required a large crew to handle it all. And even with all of that you could only move when and where the wind was blowing.

By the beginning of the nineteenth century the world had five thousand years invested in sailing technology. And living with wind technology meant that the advantages of steam power were obvious.

A steam ship could leave port when it wanted to, and even travel against the wind. The crew could be a tenth of the size needed on a sailing ship, which meant more of the power was used for moving cargo and less for moving the crew. And crews are expenses.

The cargo is the profit. And the new nation of America had a shortage of manpower, meaning a shortage of sailors. Steam ships were the obvious solution to increase profits And that is what capitalism is all about. Because it sure ain't about efficiency. That is the other great secret of capitalism, which is that "the check is in the mail".

Anyway, in 1818, the successful Savannah Georgia cotton merchant William Scarbrough (above) paid $50,000 for a 319 ton packet ship then under construction at the Fickett and Crockett shipyard, on the East River, in New York City.

Mr. Scarbrough was president of (and principle investor in) the newly formed Savannah Steamship Company, based in his adopted home city of Savannah, Georgia (above) William was intent upon establishing a regular steam ship service between America and Europe. And to shepherd that intention into reality Scarbrough sought out Captain Moses Rogers.

Moses Rogers (above) seemed to have been born at almost the perfect time and place for a young man with a maritime heritage, a mechanical bearing of mind and an adventurous spirit. Fifty years earlier many of those talents would have been wasted. But at the turn of the 19th century he seemed to be perfectly positioned - seemed to be.

He was pure Yankee, born in New London, Connecticut. He had been one of the first captains of Robert Fulton’s “North River Steamboat” (Later called the “Claremont”) (above), and in June of 1808 he had shared command of John C. Steven’s steamboat “The Phoenix”. Stevens had missed beating Fulton to the honor of first steamboat in America by just a month, and missed profitability by not having the Governor of New York as his partner.

While Governor Livingston had granted Fulton (his partner, of course) the sole right to operate steamboats on the Hudson River, Steven’s "Phoenix" (above) was forced to use the riskier runs between New York and Philadelphia. And it was in coastal waters that Rogers built his reputation as a navigator and an engineer, because the steam engines kept breaking down. Captain Rogers had even discussed the idea of oceanic steamships with Stephen Vail.

Vail (above) owned an iron works in Moorestown, New Jersey, and employed engineers who had worked with Watson Watt, the developer of the original steam engine. Vail’s engineers not only had personal experience at building steam engines but they had also managed to smuggle vital data about the engine design out of England. It seemed like a partnership of these three men, Scarbrough, Stevens and Vail, was made in heaven. How could they fail? I shall pause now while we all snicker.

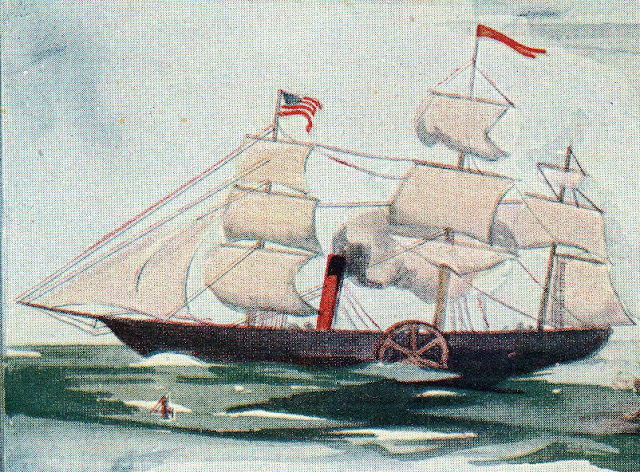

On 22 August, 1818 the newly named “Savannah”, 98’6” long by 25’10” wide, with three masts and a man’s bust for a figurehead , slid off the ways in upper Manhattan and immediately sailed to Vail’s Speedwell Iron Works, at Mooristown, New Jersey (above) where a 90 horsepower 30 ton steam engine, removable side paddle wheels and a 17’ bent smokestack were installed. The work took six months.

On 29 March 1819 the Savannah (above) sailed on her shakedown cruise to her namesake port. Then on 22 May she set sail for Liverpool, England. Scarborough could already smell the money piling up in his pockets.

The correct word here is “sailed” as the Savannah’s engine gobbled up to 10 tons of coal a day. She could only carry 75 tons (with about another 5 cords of wood as an emergency backup). Besides, under sail, the Savannah could make 10 knots an hour, while under steam alone she could only average about 5 knots. So the steam power was used only when the winds failed. She used her steam engine less than 80 hours in total during her crossing.

The Savannah broke no speed records. She covered the 3,000 miles in a mediocre 22 days, and ran out of coal in the process. The boilers had to be fed the wood so the Savannah could make her "grand entrance” into Liverpool (above) under steam.

The British were not impressed. In the first place they had not invented the thing, the Americans had. Pish posh, and poo poo. It seemed to the Limeys that the limited power of the steam engine was not worth the loss in the cargo space the engine took up. And they were right.

Given the cold shoulder by English investors, the Savannah sailed for Copenhagen, where the King of Sweden offered to buy the ship for $100,000. Not having been authorized in advance to sell the ship, Captain Rogers said no. Ah, if he had only said yes, this story might have had a happier ending, because back home in America, the nation was being rocked by the Panic of 1819, and Mr. Scarborough needed an immediate cash infusion.

Record numbers of people in Boston were sent to debtors’ prison. In Richmond, Virginia, property values fell by half. Farm workers, making $1.50 a day in 1818 were,earning fifty-three cents a day a year later. Wood cutters were being paid thirty-three cents for a cord of wood in 1818, but only ten cents for a cord by 1821.

And one of the bigger victims of the panic was William Scarborough, and his Savannah Steamship Company. On 15 June, 1819 Scarborough had to take out a mortgage on his new mansion (above) to secure his debts, which then totaled $87,534.50. A year later, 13 May, 1820, Scarborough was forced to sell his beautiful home to Robert Isaac, his brother-in-law, for $20,000. He had to sell his house to his brother-in-law; that must have stung!

Oh, Isaac allowed William to continue to live in the house. But the very next day he laid claim to everything else that Scarborough still owned, including his shares of the steamship Savannah.

Once back in America The Savannah was stripped of her boilers and put back into service as a standard packet sailing ship. She was a failure at that too. In November 1821, in a gale, she ran aground and broke up off of Long Island, New York. Gee, I hope she was insured.

Stephen Vail, whose Speedwell Iron Works had installed the engine on the Savannah, was still owed $3,527.84 for his work. He never got paid. Moses Rogers went back to work running a dull coastal steamer, the “Pee Dee”. He died of yellow fever at Georgetown, South Carolina on 15 November, 1821, at the age of 42. And somehow I am sure a contributing factor to his early death was his loss of faith in The Savannah.

William Scarborough, the inspiration for this noble misadventure, lived out the rest of his life in his own home, (thanks to his brother-in-law), even leaving it to his daughter in his will, just as if he still owned it. He died in 1838, at the ripe old age of 62 and is buried in the Colonial Park Cemetery in Savannah. Honestly, his grave looks more like a homemade backyard barbecue.

His home is still standing. It's address is now 42 Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard, an address which might take some explaining to an old slave holder from 1818. But the building now houses "The Savannah “Ships of the Sea” Maritime Museum" (above), featuring a model of that amazing failure, the steamship Savannah. And that should make the old man proud.

The steamship Savannah (above) was a good idea. But like most ideas, good and bad, it was judged a failure. Nobody got rich off the Savannah and most people associated with her went broke. And that is why they should be remembered. It's the way capitalism is supposed to move forward. If death is required to give life meaning, then failure is required to give capitalism meaning.

And somebody should explain that to the Wall Street Bankers and the Health Care Leeches who think they are entitled to suck America dry so they can avoid going broke. Please remember, luck should always part of the balance sheet. The S.S. Savannah should serve as yet another reminder of that.

- 30 -