I should point out that when Martin Van Buren (above) was dumped into an Indiana hog wallow, ruining a very expensive pair of pearl gray trousers and coating his elegant frock coat with everything a happy swine leaves behind in a porcine sauna, he deserved it.

Of course “The Red Fox of Kinderhook” was far too crafty a politician to admit he had been humiliated. That would just draw more attention to his humiliation. As the venomous Virginia politician John Randolph observed, Martin Van Buren always “rowed with muffled oars.” But everybody knew this traffic accident had been staged as payback for Van Buren's insult to Hoosiers. What goes around comes around. And it was useless to point out that the insult to Hoosiers had mostly come from Van Buren's predecessor, the still popular Andrew Jackson.

Even the frail shadow of federal authority which existed in 1828 was too much for President Andrew Jackson. Over his two terms, he did his very best to weaken the Federal government, in all its endeavors except the ones he approved of. Jackson vetoed a new charter for the National Bank - precursor of the Federal Reserve - which left the entire banking system unregulated. He streamlined the sale of public lands, which energized the speculators who were overcharging the yeoman farmers. He cut entire programs out of the Federal budget, and insisted the states take over many others. And at the same time he backed the Seminole Indian nation into a war.

But it was not until three months after Van Buren's inauguration in March of 1837 that these pigeons came home to roost. The massive real estate bubble Jackson had inflated, suddenly popped. Over half of the nation's unregulated banks suddenly failed. And by January of 1838 half a million Americans were unemployed. Or to put it more simply, suddenly it was prom night and Martin Van Buren was Carrie.

And like Carrie, Van Buren then made things worse by slashing out at everything in sight. Oh, he continued the unending and expensive Seminole war. But he insisted on killing Federal funding for the National Road, which had reduced mail time between Washington, D.C. and Indianapolis from several months to less than a week. Van Buren was so doctrinaire he even sold off the road builders' picks and shovels. And for frontier farmers trying to get their produce to market, that made any economic recovery that much harder. In fact, the whole economy was falling into a hole.

See, once the National Road crossed the Ohio border, the $7,000 per mile construction costs were supposed to be paid for by land sales along the route. But when the real estate bubble popped in 1837, that funding evaporated. Maintenance for the 600 mile road was paid for by the tolls of four to twelve cents (the equivalent of $2.50 today) for each ten mile long section, paid by the 200 wagons, horseback riders, farmers and herds of livestock that used each section of the road every day. But after 1837 that $36,000 a year (almost a million dollars today) had to do double duty, finishing the road and providing maintenance for the road already finished. And it was not enough money.

In Indiana there were long sections beyond the two urban centers, ((Indianapolis and Richmond, Indiana) where farmers using the road to drive their livestock to market faced forests of 14 inch high tree stumps. These provided clearance for the farmers' and emigrants' high riding Conestoga wagons, but between the stumps, the road bed was in such bad shape that constant repairs to their equipment bankrupted many of the 200 stagecoach lines trying to survive in Indiana.

And every frontier farmer and businessman knew exactly who was to blame for all of this –“President Martin Van Ruin”. As a result, in the election of 1840, in Hendricks County, (just southwest of Indianapolis), and along the now almost abandoned National Road, Van Buren received 651 votes, while successful Whig candidate William Henry Harrison received 1,189 votes. Nationwide, Van Buren carried just 7 of the 26 states. That was how the Wigs won the White House in 1840.

Normally this Hoosier hostility would not have mattered much, but just six months after taking office, the new President Harrison died of a pneumonia, and all previous assumptions had to be rethought . The Whigs had picked John Tyler as Vice President, mostly to get rid of him. Now, disastrously, he was the head of their party. The overjoyed Democrats began referring to Tyler as “His Accidency.” The dapper Martin Van Buren began thinking he could avenge his defeat and take the road back to the White House in 1844. All he needed was a cunning plan, which he just happened to have.

In February of 1842, Van Buren (above) journeyed to Nashville, Tennessee, for an extended visit with his mentor, Andrew Jackson, hoping some of Old Hickory’s popularity would rub off on him. It did not. Heading north wit the spring, Van Buren then set off for a tour of the frontier states. He was well received in Kentucky, and the pro-slavery areas around Cincinnati, Ohio, but the closer he got to Indiana and the decaying national road, the more reserved the crowds became.

On 9 June, 1842 Van Buren was met at the Indiana border by 200 loyal Democrats. He gave them a speech to a cheerful crowd at Sloan's Brick Stage House, on the north side of Main Street (the National Road), between 6th and 7th streets, in Richmond. But the vast majority of the local Quakers remained skeptical. And while Van Buren was speaking, noted the Richmond Palladium newspaper, “...a mysterious chap partially sawed the underside of the double tree crossbar of the stage(coach)...so that it would snap on the first hard pull…”

The next morning the stagecoach and its distinguished passenger headed toward "The Capital in the Woods" - Indianapolis. But just two miles outside of Richmond, while bouncing over ruts and stumps, the carriage splashed into a great deep mud hole. And when the horses were whipped to yank the carriage out, the weakened cross brace snapped. Dressed in his silk finery, Martin Van Buren was forced to disembark into the foul waters and wade to shore.

There was no indication of any further sabotage on Van Buren's 74 mile ride across the mostly open prairie, which took the better part of three days because of the road's condition. And the ex-President and candidate made it to the Hoosier capital in time to keep his appointments and make his speeches over the weekend of June 9-10. He took two more days to make solidify political contacts, shaking hands and trading confidences, before, on Wednesday, 13 June, he boarded yet another mail coach for the 75 mile journey to the Illinois border. But just six miles down the road, Van Buren had to pass through another Quaker bastion, this one called Plainfield, Indiana.

The town earned its name from the “plain folk” who had laid out the grid ten years earlier on the east bank of White Lick Creek (above). This Henricks county town was straddled by the National Road, which provided Plainfield's livelihood.

Less than a quarter mile east, up Main Street from the ford over the "crick", amidst a stand of Elms, the Quakers had cleared a camp ground and built a meeting house. And here, that Wednesday morning, were gathered several hundred Democrats and Wigs (mostly Quakers in their “Sunday, go to meeting clothes”), to see the once and maybe future President ride past.

The crowd may have even been increased because the driver of this particular leg of the ex-President's journey was a local boy, twenty-something Mason Wright. Soon, the crowd heard the blast of Mason's coach horn, warning of the VIP's bouncing approach down the gentle half mile slope toward White Lick Creek.

The disaster occurred abruptly. The coach rushed into view, with Van Buren's arm waving out of the coach's open window, while Teamster Wright whipped the horses to move faster. Faster? Shouldn't he be slowing down to let people get a view of the President? And then, just as the carriage came abreast of the center of the campground, the coach was forced to veer to the right to avoid a large "hog waller" mud hole in the very center of the dilapidated National Road.

And then, as if it had been planned, the right front wheel bounced over the hard knuckle of an exposed bare elm root. The carriage teetered for an instant until the rear wheel clipped the same root. The teetering coach then careened past the point of no return. Mason Wright leaped free while the coach crashed heavily onto its side into the very center of the smelly, sticky, hot black hog waller. Martin Van Buren had been dumped upon. Again.

A Springfield Illinois newspaper would note a few days later, “He was always opposed to that road, but we were not aware that the road held a grudge against him!” Wrote a more bitter Wig newspaper, “the only free soil of which Van Buren had knowledge (of) was the dirt he scraped from his person at Plainfield.”

The driver and witnesses blamed the elm (above), which could not defend itself. Van Buren was uninjured, but once again had to extricate himself from his injured coach. After pouring the mud and other unidentified muck from his boots, Van Buren made his way on foot further west along the National Road to Fisher’s Tavern, at what is now 106 E. Main Street. There, Mrs. Fisher helped the President clean up his pants and coat, and wash the mud from his expensive wide brimmed hat.

Back at the campground. the honest Quakers helped right the stage, re-attach the horses, and carefully and respectfully delivered the coach to Fishers to collect the President. But it is hard to believe that, as Mr. Van Buren splashed across White Lick "crick" many of those Quakers were not smiling with the sly satisfaction of a job well done.

A few days later Teamster Mason Wright was awarded a $5 silk hat, although it was never explicitly stated it was for his skill in staging the crash - call it political slapstick. But the tree who's root had provided the fulcrum for the prank would forever more be known as the Van Buren Elm. In 1916 (above) the Daughters of the American Revolution even gave the tree a wooden plaque of its own. Which, unfortunately, they nailed to the tree.

Van Buren made it safely to Illinois without further accidents. He was met a few miles outside of the state capital of Springfield by a small delegation of legislators, including the young Abraham Lincoln. But Mr. Van Buren was never elected to public office again. The judgement of Hoosiers stood firm.

The Quakers' Meeting House (above) still stands among the Elms at 256 East Main Street (corner of Vine) in Plainfield, although rebuilt a few times.

After the original Van Buren Elm fell in 1926, a replacement was planted, and in memorial, the old tree received a bronze plaque (above) embedded this time in a stone.

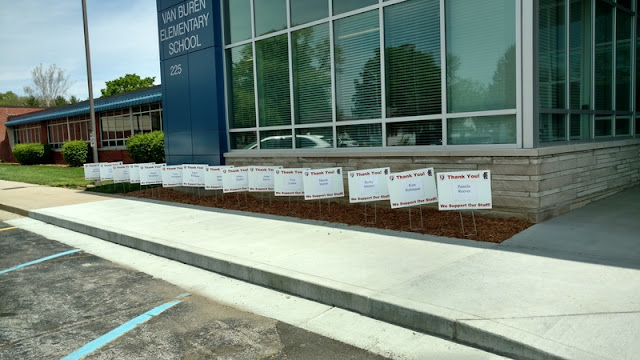

The Elm also enabled a local grade school (above) to be named for the dapper Democrat who had stumbled in their town, and a street was named after him as well.

In Plainfield the National Road (now U.S. Route 40), still slips down the slope toward White Lick Crick (above), and is still called Main Street. That is true of many towns bisected by the old National Road. They truly were America's first Main Street. Both Martin Van Buren and Andrew Jackson were wrong about that. But it was Van Buren who took the fall.

- 30 -