I take it as a sign of how bad a reputation George Hull had earned even before the Cardiff Giant, that he dare not let the public suspect he had any part of the 2 ½ ton precipitate lump. Hull stayed in the background, while his farmer/cousin William Newell, played the owner and sold a majority share to the Syracuse syndicate. But as December was approaching George instructed his cousin to sell their remaining ¼ share of the giant. The buyer was Alfred Higgins, the Syracuse agent for American Express, a three term alderman for the city of Syracuse, and a lifelong bachelor. It is unclear how much Higgin paid for his share in the unwieldy trinket.

The giant now belonged solely to citizens from Syracuse. Up to then the fame of the town of 40,000 rested on the brine springs on the south side. But now “Salt City”, which supplied preservative to the entire country, could also be known for the entrepreneurship of its most illustrious citizens, David Hannen, Dr. Amos Westcoff, Amos Gilbert, William Spencer, Benjamin A. Son, and now Alfred Higgins. Even the services of Ohio showman Colonel J.W. Wood, were dispensed with. The Syracuse Six then proceeded to transport the Cardiff Giant to the Yates Ballroom of the Geological Hall, at State and Lodge streets, in Albany, New York. But Barnum was not to be outdone..

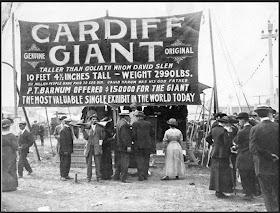

Using the advertisements of the Syracuse Six as a guide, the King of hokum had a plaster giant of his own made and painted to resemble the stone behemoth. And then, because his own museum was still in ashes, Barnum offered his giant for public perusal in Mr. George Wood's (no relation) Museum and Metropolitan Theater, at 1221 Broadway. Barnum's newspaper ads did not, of course, admit to displaying a copy. Barnum asserted the “Albany Giant” was the copy, while Barnum's plaster man was the original.

Readers of the Buffalo Express on Saturday, 15 January, 1870, found an article under the title, “A Ghost Story, by a Witness ”. The author claimed to be living in Manhattan and so short of funds that he had moved into an abandoned hotel on Broadway. He was terrorized by groans and apparitions all night long, until the ghost finally appeared and explained, “I am the spirit of the Petrified Man that lies across the street there in the Museum. I am the ghost of the Cardiff Giant. I can have no rest, no peace, till they have given that poor body burial again” To this sad tale the writer responded, “Why you poor blundering old fossil, you have had all your trouble for nothing -- you have been haunting a PLASTER CAST of yourself -- the real Cardiff Giant is in Albany!”

The original inventor of all this, George Hull, must have been gobsmacked. How could this reprobate have ever imagined that his fraud, so carefully crafted and executed could be turned inside out - a humbug made of his humbug. It was unbelievable, incredible, absolutely amazing. It was a lesson from the old master himself. You think you know the “con” game, Barnum seemed to be saying You ain't seen nothing yet. The crowds that now jammed Wood's Theater and Museum and the Geological Hall, all knew their legs were being pulled, and were all loving it.

And then a little purple pamphlet appeared for sale in Albany. The title page read, “THE CARDIFF GIANT HUMBUG—THE GREATEST DECEPTION OF THE AGE” The author was Benjamin Gue, editor of the Fort Dodge, Iowa, “North West”. Between the covers were names, dates, bills of lading, interviews and witness statements documenting the creation of the Cardiff Giant, from the 1867 appearance of Mr. Martin in Fort Dodge, through the July 1868 shipment of the stone from Boone, Iowa, to Chicago, to the studio of Eduard Burkhardt, to the giant's arrival in Union, New York. There were eyewitness memorials of the journey to within three miles of the Newell farm in Cardiff. Gue had even uncovered records of the fund transfers between Stub Newell and the evil genius, George Hull. The diligent Mr. Gue had even investigated Mr. Hull's career from marking cards, to selling cigars, to inquiring into Wisconsin Indian burial mounds, to the Cardiff Giant. Most of what we can now confirm about George Hull, we know because of editor Gue. It was a hull of a story.

The pamphlet was on sale for a few hours before someone bought out the entire edition. However, because Mr. Gue had contracted with a printer in Albany, the next day the newsstand was again fully stocked with “The Cardiff Giant Humbug...” The printer and the author didn't care if the pamphlets were being read or being burned. They were just interested in selling them. The Syracuse syndicate issued a statement denouncing the pamphlet as its own fraud. But the truth was, the truth didn't matter. The public took to calling the giant, “Old Hoaxy”, they still paid to look at it. As Barnum said, “Every crowd has a silver lining”.

The crowds in Albany did drop a little after the pamphlet appeared, but unless the giant expanded his repertoire by juggling or doing a soft shoe, once you had seen the Cardiff Giant, there was little interest in seeing it again. So the pamphlet revealing the fraud was just another revenue stream, like Mark Twain's ghost story in the Buffalo paper. Barnum knew the real craft in advertising, or humbug as Barnum called it, is what I call the “Pet Rock” paradigm. People will buy a “pet rock” as long as they know you know that they know its actually just a rock.

It appears the only person who failed to figure out that rule was the horse trader David Hannum (above), who demanded an injunction to stop P.T. Barnum from claiming that "The Albany Giant" here after referred to as the "Fake Giant“ was the fraud, and not Barnum's "Fake, fake giant".

The hearing on 2 February, 1870, was held in New York City, before Judge George G. Barnard (above), a Tammany Hall jurist so corrupt that in two years he would be impeached and bared from ever holding public office in New York state again. Judge Barnard heard the case presented by Hannum and then from Barnum's lawyers, and even from George Hull, who admitted for the first and the only time under oath that he had created the Albany Giant.

Judge Barnard told Mr. Hannum (above), “Bring your giant here, and if he swears to his own genuineness as a bona fide petrifaction, you shall have the injunction you ask for.” Baring that event, he said, he was out of the “injunction business”.

Leaving the courtroom, David Hannum was asked why he thought his original fake giant, which had moved to New York City in December, was drawing smaller crowds than Barnum's fake fake giant. He shrugged and then uttered the immortal words, “There's a sucker born every minute.” Barnum was later blamed for the quote, but he never called his customers suckers. Hull and Hannum both did. and maybe that was why, the day after Judge Barnard's decision, Barnum's fake fake drew a huge crowd, while Hannum's original fake drew almost nobody. But on the second day, even Barnum's fake drew only 50 customers. It seemed, with the high drama and courtroom farce, the Cardiff Giant had run out of humbug.

The two giants went their separate ways, never having met. And over time they were both reduced to appearing in county fairs, and side shows and finally in museums of fakes and frauds. But, it must be said, they both continue to produce a profit for their owners, however small.

Not long after the lost injunction, David Hannum was on board a train when a man asked him to move over a seat. Hannum refused. Sharply the man demanded, “Do you know who I am? I am P. Elmendorf Sloan, the superintendent for this railroad., and my father is Sam Sloan, president of this railroad.” To which Hannum replied, “ "Do you know who I am? I am David Hannum and I'm the father of the Cardiff Giant." Well, adoptive father, maybe.

Like the other investors in the “Albany Cardiff Giant”, Doctor Amos Westcoff made money. But for whatever reason he rose from the breakfast table on 6 July, 1873 , went upstairs to his bedroom, and shot himself in the neck. He died quickly of blood loss. His partner, Alfred Higgins, never lost faith in the giant, and until his dying day remained convinced it was a petrified man, straight out of the pages of the Holy Bible. The Reverend Turk, blamed for inspiring the Cardiff Giant, died in 1895, in Iowa. He accepted no guilt whatsoever. And that I think is the primary advantage of blind faith.

George Hull made a small fortune from his fraud, and invested it in a commercial block in downtown Binghamton, New York. But his profligate lifestyle quickly ran through his profits, and within five years he was almost broke again. So....he conceived of an even bigger stone giant - this one with a tail.

The “Solid Muldoon” was “discovered” outside Pueblo, Colorado on 16 September, 1877, and attracted crowds in Denver and Cheyenne, Wyoming. But by the time the Colorado Giant reached New York City, the scheme had gone bust . Gloated a Binghamton newspaper, “This would seem to stop the Giant Man...getting rich without working.” Little did the editorial writers realize how much work George had put into his frauds.

Shortly thereafter, the long suffering Hellen Hull died of consumption at 42 years old. The atheist George allowed her to be buried in a Methodist service. The evil genus himself went broke and was reduced to living with his daughter in Binghampton, He died on 21 October, 1902. Perhaps the most accurate thing he ever said was “I ought to have made myself rich, but I didn't.” Still, recorded another paper's obituary, "Hull was very proud of the (Cardiff Giant) affair, and he never tired of talking about it." Fifteen days after George's death, in Chicago, the man who had carved the Cardiff Giant, sculptor John Sampson died.

Barnum's Giant, the fake, fake fraud, currently resides in Farmington Hills, Michigan, inside “Marvin's Marvelous Mechanical Museum”.

Since 1947, George Hull's original fake has been in Cooperstown, New York, reclining behind a white picket fence inside the “Farmers Museum”.

And every fall, the folks at the LaFayette Apple Festival, in tiny Cardiff, New York, provide a walking tour to the Newell farm, the site of the temporary grave for the Cardiff Giant.

They recreate his discovery and exhumation, around a plaster giant, and I urge you to visit this and the other sites, just to remind yourself to never pass up a chance to laugh at yourself. . It's very healthy. I believe P.T. Barnum himself endorsed it.