On Sunday, 5 April, 1863, about 50 old men and boys of the Tensas Parish mounted militia - AKA the 15th Independent Louisiana Cavalry - were on a "training patrol" along the eastern shore of Bayou Vidal, in one of the richest cotton growing parishes of cotton rich Louisiana.

The parish had 118 plantations, a third of which held more than 100 humans in bondage. After two full years of war slaves in the parish now outnumbered white males by two to one, heightening white fears of a slave revolt.

Late that afternoon the militia spotted a couple of Negroes paddling a flatboat across the bayou. With Yankees at Richmond, Louisiana, all boats had been ordered held on the eastern shore. The whites ordered the slaves to halt. And when the command was ignored the militiamen fired on their disobedient servants.

And to the white men's shock, somebody shot back. One militiaman was killed and another wounded. They rushed back to inform their commander, Major Isaac F. Harrison that the Yankees had come to Tensas Parish.

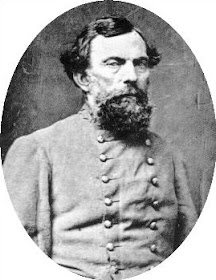

Major Harrison's first responsibility was to notify his superior officers, up the ladder to the deaf and cranky 59 year old Lieutenant General Theophilus Hunter Holmes (above). But that seemed a pointless exercise because Holmes owed his exalted appointment to his incompetence, which had driven General Robert E. Lee to demand his removal from the eastern theater, and his long friendship to Confederate President, Jefferson Davis, who then made his incompetent friend Commander of the Trans Mississippi. Besides, Holmes was far away in Little Rock, Arkansas, obsessed with guarding the few resources his department was holding on to. So Major Harrison sent notice not only to General Holmes but also to the nearest commander in the neighboring Department of Mississippi - 32 year old Georgian, Major General John Stevens Bowen.

Bowen (above) was a competent field commander, but his division at Grand Gulf, Mississippi actually numbered little more than 5,000 men. Still, he told his boss, Lieutenant General John C. Pemberton, in far off Jackson, Mississippi, that he wanted to send some men across the river to find out what Grant was up to.

General Pemberton had suspicions about Bowen. After the battle Corinth the previous year, the Georgia native had filed charges of incompetence against his superior, General Earl Van Dorn. The General was found not guilty, but the stink of betrayal lingered over Bowen and made him suspect. Besides, Pemberton doubted the Yankees were moving south. Earlier - on Friday, 3 April, 1863 - all but 7,000 men of General Nathaniel Bank's 35,000 man Federal Army of the Gulf had disappeared from lines defending Baton Rogue, on the east bank of the Mississippi. Pemberton had no idea where those 28,000 blue coated soldiers had gone, but it seemed unlikely Grant would be moving south to cross the river if Banks was no longer there to reinforce him.

Also, scouts reported there was heavy steam boat traffic on the Mississippi between Milliken's Bend and Memphis, above Vicksburg. This seemed to indicate Grant was shifting his army for another invasion of northern Mississippi. No, the Yankees at New Carthage were just a raiding party - at least that's what it looked like from Pemberton's perspective in Jackson. So he told Bowen to go ahead with a reconnaissance of Louisiana, but to remain ready to re-call those men if they were needed in Jackson.

On Thursday, 9 April, the 1st and 2nd under strength Missouri rebel regiments, under 28 year old lawyer and politician, Colonel Francis Marion Cockrell (above), crossed the river to Hard Times Landing. Cockrell was to find out what the Yankees were doing in Louisiana and if they were serious about it. So he pushed his infantry 6 miles north up the levee road beyond the head of the crescent Lake St. Joseph, south of New Carthage. There they bumped into the advance party of the 49th Indiana Volunteers.

Among the Hoosiers was Doctor John Ritter, and from his perspective the Yankees were a real threat. "The Rebs", Dr. Ritter wrote his wife, had "occupied the high land down (to) the river. Their pickets were in sight all the time...We threw up breast works across the levee below and by that means held them in check...but if they had planted their artillery they could have shelled us out..." Except Cockrell had no field guns. So after staring at each other for 5 days Colonel Cockrell decided to provoke a response by falling on an isolated company of the 2nd Illinois Cavalry, occupying the central houses of a plantation owned by Judge William Dunbar, guarding the Yankee right flank along Mills Bayou.

On the afternoon of the Tuesday, 14 April, members of the 1st Missouri left their positions along Bayou Vidal and marched west, crossing Mills Bayou, before swinging north behind the Federal positions. After a few hours of fitful sleep, at 4:00am the next morning, they waded into the waist deep water of the bayou again, falling on the Yankees without warning. In the dark the Missourians were able to capture one sentry, and kill a second before the Yankee cavalrymen awoke and fell back from the main house in confusion.

Still in the dark, the Missourians gathered up the wives and children of the overseers and other white employees who had been left behind. They also rounded up the 100 slaves in their cabins, driving the frightened people like cattle back across Mills Bayou in the dark. They also claimed to have discovered a chaplain of the 2nd Illinois "entertaining" a “young, full grown, athletic” slave woman in a back room of the big house. The truth of that situation can never be proven because no one's version of events can be taken as gospel.

By dawn additional federal units had been awakened, and part of the 10th Ohio Infantry regiment joined the remainder of the 2nd Illinois in driving on the plantation with artillery support. Shortly after dawn the rebels were all safely back across Mills Bayou, taking any of their dead and wounded with them, leaving the Federals to claim only one rebel captured, in exchange for 1 dead, 2 wounded and 2 missing. It was not much of an engagement, unless you unlucky enough to have been shot or killed. But the rapid counter attack by the 10th Ohio, told Colonel Cockrell that there was strength behind this move south, and that it was not likely these Yankees were a mere raiding party.

The nervous Dr. Ritter, feeling vulnerable and isolated atop the open levee south of New Carthage, was not as alone as he felt. Behind him Federal engineers were directing the work of the the 1st Missouri Federal and the 127th Illinois and 34th Indiana infantry regiments building a dam...

...and 4 bridges - one 200 feet long - across flooded countryside, and widening to 20 feet and improving and "corduroying" 40 miles of road from Richmond to New Carthage, and " the road from Miliken's bend to Richmond, Louisiana.

Soldiers have been building corduroy roads across swamps for 6,000 years, and the process is simple. It merely requires unlimited manpower, and vast quantities of young trees. First, you clear the roadway, not only of trees but of stumps. Ideally you dig out the roadbed to a depth of a few inches. Then you lay felled trees, each 4 to 6 inches in diameter, across the road, packing the trunks as tightly together as you can, using branches and mud to chock the logs and keep them from rolling under the pressure of a passing legion, a single horse or a wagon. Then you cover the "road" in the mud dug out earlier, to cushion the impact of traffic and to provide safe footing for the horses.

During the American Civil War only the Yankees seemed to build corduroy roads. Observed a member of the rebel Army of Northern Virginia, "...the roads might have been ‘corduroyed’ according to the Yankee plan...but timber was not to be procured for such a purpose; what little there might be was economically served out for fuel." A corduroy road could strip a forest of a human generation worth of trees.

In fact the Federal armies got pretty good at it, learning that a fence stripped of its posts would provide enough wood to corduroy half its length in road. But no corduroy road would survive long under the intense pressure of military use. And marching 50,000 men over the 12 miles of corduroy road between Young's point and the Desoto Peninsula, would destroy the entire structure, even before the endless supply trains required to feed the men and horses which had marched down that same road.

But Grant "doubled down" on this approach. Besides the 40 mile interior route to New Carthage, he ordered the improvement of a second, shorter route, 8 miles long atop the levees directly from Young's Point to the shore of the Desoto Peninsula south of Vicksburg. But then, Grant had no intention of supplying his army down either road he chose to march over.

Federal troops taking the shorter route would be fully visible to Confederates in Vicksburg, while the inland route was masked from enemy view. Also, Grant discovered that although the digging had not added enough depth to the bayous to make them usable for shipping, it had deepened them enough to form a flooded obstruction to any rebel infantry from the west wishing to interfere with the march south.

So by 15 April, the day Colonel Cockrell's Missourians had poked at the Federal's right flank, Grant was ready to order the Hoosiers to push further south, toward Lake St. Joseph and beyond to Hard Times Landing, to make room for the remainder of General McClernand's Corps, and the rest of the army behind them.

Grant's goal seemed obvious, from his perspective at Millinken's Bend. But Pemberton was high and dry in Jackson, Mississippi. Pemberton did not awaken every morning to the sound and smell of the river. He had not been living next to it and on it for three months, as Grant had. Pemberton's perspective inclined him to look to Grant's army, when his eyes and ears should have been following Grant's brown water navy.

- 30 -