I find it instructive that the citizens of Halifax, Nova Scotia (above) have never obsessed over how the disaster of 6 December, 1917 could have happened to them. They have asked the obvious questions, but have been willing to quickly accept that they would never know the whole truth. In part this was because so many of those responsible were already dead, and in part because it was a time and a place where obsessions could not be tolerated. There was a war on, as the saying goes, and that explained the unexplainable, as you would know if you have ever considered the full implications of that phrase; “There’s a war on.”

Halifax exists because it is one of the largest, best protected ice free harbors in the world, a gift of the Sackville River. The Sackville rises in the center of “New Scotland” near Mt. Unijacke and meanders its way for 25 miles south eastward, spilling from one lake to another until it reaches the head of The Bedford Basin.

Here the Slackville disappears into a drowned river valley, a protected anchorage four miles long by two miles wide. At its southern end is “The Narrows”, which closes to a little less than a mile wide channel. In 1917 the town of Halifax, home to 50,000, rose on the steep hills along the west side of the Narrows, while the suburb of Dartmouth, with a population of 6,500, occupied the east shore.And beyond the bottleneck of The Narrows was Halifax Harbor, which opened directly to the North Atlantic. The salt water here is warmed by the nearby Gulf Stream Current, and the Great Circle commercial route is just one hour sailing time out to sea. That combination, the harbor and the nearby Great Circle Route, made Halifax a convenient place to rest and load coal before challenging the North Atlantic, or to recover after a harrowing voyage to the new world. And during World War One the Bedford Basin was the logical place for allied convoys to form up in safety, far from prying enemy eyes.

Early on the morning of Thursday, 6 December, 1917 there were some fifteen cargo ships crowded into the Basin and several Royal Navy warships in Halifax harbor.

But atypical of all of these ships was the Steam Ship Monte Blanc; 3,121 tons, 320 feet long, and inbound for Bedford Basin. At any other time she would have been a pariah, and expected to unload her cargo outside the port, on the safety of McNab's Island. But there was a war on.

The SS Mont Blanc was just out of New York carrying 2,300 tons of the explosive trinitrophenol (TNP), 200 tons of trintritoluene (TNT), 10 tons of gun cotton and 300 rounds of small arms ammunition. In addition she had 36 tons of the high octane Bezol fuel piled about her decks in 50 gallon drums. In short the ship was a floating bomb. And as the Monte Blanc approached The Narrows she found herself head-on to the outbound 5,043 ton, 430 foot long Norwegian SS IMO, running ballast, outbound for New York to load humanitarian supplies for occupied Belgium.

As the two ships approached they each signaled by ship's horns their intention to maintain course and speed. Then without warning the Mount Blanc turned to the right, as if moving to dock at a pier on the Halifax shore. Seeing this, the Imo (below) desperately reversed her engines, intending to slow and give the Mount Blanc room. But the reverse spin on Imo’s propeller pulled her into the center of The Narrows, and directly into the path of the looming Monte Blanc.

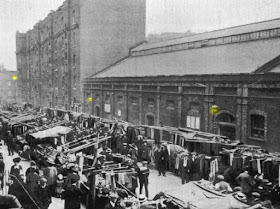

It was 8:45 A.M., local time. The towns of Halifax and Dartmouth were just starting their work days. Large crowds stopped to watch as the two ships sounded their horns in alarm and drew inexorably together. Workers at the new rail yards up the harbor were drawn to the excitement. Everyone in town, it seemed, stopped what they were doing to witness the drama unfolding.

As if in slow motion the two ships struck. The Imo’s prow sliced into the starboard bow of the Monte Blanc. Benzol drums were thrown about Monte Blanc’s deck, spilling the corrosive fuel. Mont Blanc’s cargo hold was penetrated. For a long moment the two ships hung there in the middle of The Narrows. Then, as the Imo backed away, the scrapping of crumpled metal against torn metal, threw sparks. A fire quickly broke out aboard the Monte Blanc, ignited or fed by the Benzol, sending grey smoke skyward. Within 10 minutes the Mont Blanc’s forty man crew had been forced to take to their life boats. Once there they shouted a warning for the Imo’s crew about their volatile cargo. But none of the Imo's crew spoke French. The drifting burning hulk now brushed past Halifax’s pier six, setting it afire as she passed.

The Canadian Navy tug and mine sweeper "Stella Maris" (above) joined the Imo in attempting to throw water on the fires, and the "Stella Maris" also sent a boat crew to attempt to take the abandoned wreak under tow.

Meanwhile the Box 83 alarm at the Halifax Fire Department sent men and equipment racing toward the harbor and the burning dock. They arrived there just after 9:00 a.m., forcing their way through the growing crowd along the shore, all drawn there by the spectacular show. Almost no one in the harbor knew what the cargo of the Monte Blanc was.

But even now a few sensed the impending disaster. Mr. P. Vince Coleman, a dispatcher for the Inter-Colonial Railway yards (above) just a few hundred yards inshore from the piers, not only saw the accident, but knew of the Monte Blanc’s deadly cargo as well. He and other workers in the yards ran for their lives. But then Coleman remembered that a train loaded with 300 passengers from Saint John’s was due to arrive in a few moments. He ran back to his post and tapped out the following message on the telegraph key, “Stop trains. Munitions ship on fire. Approaching pier six. Goodbye.” Every operator up and down the line heard that message. Then, precisely at 9:04:35 the line went dead.

In that instant, in a single white hot flash, the 3,000 ton Mont Blanc was converted into shrapnel - jagged sections of iron weighing from slivers to half a ton. They were ripped from the hull and sent spinning away at supersonic speeds. Part of the Mont Blanc’s anchor landed two and a half miles away.

At the center of the blast the temperature exceeded 9,000 degrees Fahrenheit, instantly converting the 40 degree sea water in The Narrows to steam. First a high pressure shock wave raced through the air at 500 feet a second, flattening everything within 4 square miles. Then a fireball took just 20 seconds to rise a mile into the air, where an enterprising photographer snapped a picture (above) from thirteen miles away.

Then a tidal wave 36 feet high swept back and forth across The Narrows, sweeping away everything onshore in its path and dragging it into the water. . An entire Innuit village of 22 families on the Dartmourth shore was drowned by the wave. Windows were shattered 10 miles away. Buildings shook 78 miles distant. And the explosion was heard in Cape Breton, 225 miles to the east. Out of the tug Stella Maris’ crew of 24, only five survived. On board the Imo, the captain, the harbor pilot and five crew members were killed. The 430 foot long Imo was thrown against the Dartmouth shore like a toy in a bathtub (below), her bottom ripped out. Every other ship in Halifax harbor suffered causalities and damage.

Of the ten firemen who had just arrived at the dock, nine were killed, including the Fire Chief and Deputy Chief. The sole survivor, engine driver Billy Wells, wrote, “The first thing I recalled after the explosion was standing quite a distance from the fire engine…the explosion had blown off all my clothes as well as the muscles from my right arm.”

At least 2,000 people had been killed outright, and 9,000 wounded, not counting the Innuit dead. (Native peoples, quite simply, did not count., in 1917). More than 1,000 of those who witnessed the explosion were blinded by flying glass and slivers of wood and steel. Nova Scotia lost more of her citizens in that one instant than were killed serving in her army and navy units in all four years of World War One.

Slowly rescuers began to move into the devastated square mile, removing the dead, comforting the wounded and searching for survivors in the rubble of their homes and businesses. Then, as darkness began to fall that night, “…almost as if Fate, unconvinced the exploding chemicals…had struck a death blow to Halifax, was now calling upon nature to administer the coup de grace…”. It began to snow.

The worst blizzard in ten years buried the shocked port in several feet of snow and condemned untold injured to death by freezing.

Every year, the city of Halifax donates a Christmas tree to the city Boston, as thanks for the assistance which was rushed to them in the weeks after the explosion. And every year, on December 6th, from 8:50 a.m. to 9:25 a.m., there is a memorial service held in Halifax to remember the victims of the largest man made explosion on earth ... which was superseded only by the first atomic bomb test in 1945, when there was another world war going on.

- 30 -