I don't much like John Stanly. Sure, he suffered from abandonment issues, when both his parents died in the yellow fever epidemic in 1789, leaving him an orphan at just 15. But any sympathy for him quickly evaporates under the bright hot glare of his grudges- inventing them and carrying them were his specialty. It is not a skill usually associated with politicians, who are traditionally blessed with short memories and a laissez faire morality. But John was a skilled marketer of hate. He had no foes or opponents, only enemies. A contemporary described him as “Small in stature, neat in dress, graceful in manner, with a voice well modulated, and a mind intrepid, disciplined and rich in knowledge, he became the most accomplished orator of the State.” And at 25 he acquired his most famous enemy – three time North Carolina Governor and two term congressman, Richard Spraight.

In John's envious eyes, the elder politician (Richard was almost twice John's age) had committed one fundamental sin above all others - in 1798 the Congressman had switch from the Federalist party of President John Adams, to Thomas Jefferson's insurgent Democratic-Republican party. John Stanly had made the same switch, but earlier, and been planing on running against Richard in the upcoming election of 1800. It seemed to John that Richard had switched especially to block his career. And there may have been some truth in that. But where most politicians would have marked it down to the rough-and-tumble rules of politics, John took it as a personal affront. Besides, John decided to run against him anyway.

It was a nasty campaign, during which John accused Richard of pursuing “the crooked policy of being occasionally on both sides” of an issue - in other words, he said Richard was a flip-flopper. The charge stuck and John won the election. But winning was not enough for the ambitious young lawyer. In 1802, when Richard Spraight was standing for election to the North Carolina state Senate, Representative Stanly felt the need to insert himself into that fight, too. On the Sunday afternoon of August 8, 1802, John arose on a street corner in their mutual hometown of New Bern, North Carolina ( the “Athens of the South”) to denounce his ex- Federalist opponent to the town's 3,000 residents. During his rousing speech he also found time to again question Richard Spraight’s loyalty to the Democratic-Republican Party, saying the Federalists knew they “could always get Mr. Straight’s vote”. It was pure meanness, and it burned.

Edward did so immediately, and John, who was in the midst of his own tight re-election fight, decided it would be better to not appear to have precipitated this crises - which he had just done. So, in his reply he disingenuously reminded Richard, “you are a candidate, while I am a voter” and suggested, “I presume you will acknowledge my right to converse” on the positions of candidates for public office. But, per the code of dueling, John sent his response not directly to Richard but to Richard's friend, Dr. Edward Pasteur (a distant relation to the French scientist).

When he received John's missive, Richard decided to accept the younger man's unstated apology, writing back that he would like to publish their letters, as remarks made by supporters on both sides “may have made an improper impression on the public mind”. John agreed, and in the next week's edition of the New Bern Gazette the exchange of letters appeared, along with a few remarks on the affair by Richard.

John was out of town when the notes were published, 30 miles up the winding Trent River, attending to family business in the little brick courthouse in Trenton. It appears the business was unpleasant, because when he returned and saw Richard's comments and their notes in cold print, John was enraged. He believed he had made “humiliating concessions”, and sought to correct them in the next edition of the Gazette. His letter prompted Richard's correction of John's correction, which John then counter-counter-corrected, which Richard then corrected yet again. It all did wonders for sales of the Gazette, but the newspaper refused John's next reply, in part because the editor was John Pasteur, brother to Dr. Edward Pasteur, friend of Richard's, and because the language had begun to invite lawsuits for slander and liable.

But John was so determined to have the last word in this argument, that he paid for a handbill to be published and distributed around New Bern on Saturday, September 4th, 1802, in which he accused Richard of showing a “malicious, low and unmanly spirit”. Richard immediately responded with his own flier (printed up that very afternoon) calling John “both a liar and a scoundrel.” The three time Governor than added, “I shall always hold myself in readiness to give him satisfaction”. And that finally did it, for John. He could now justify challenging the revered politician to a duel, “as soon as may be convenient”. The older man said tomorrow would be fine, after church of course.

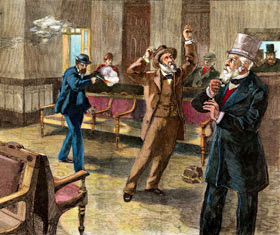

At 5:30 on Sunday Afternoon, September 5, 1802, they met on the field of honor - in this case, in the vacant lot where people tethered their horses, behind the still unfinished Masonic temple and theatre. The location was just outside the cities' jurisdiction, but convenient enough that 300 spectators showed up (today, the corner of Hancock and Johnson streets). Richard was accompanied by Dr. Pasteur, and John's second was Edward Graham. Both flintlock pistols were loaded and locked, and the two combatants stepped out 20 paces apart. And at the dropping of a handkerchief, both men fired, and both men missed.

This was not unexpected. Accuracy with a flintlock pistol was so bad that one American cavalry officer noted during the revolution that his strategy was to ride “full tilt” toward the enemy and “heave” his weapon at them. Besides, this gave the aggrieved gentlemen a chance to come to their senses, call it even and go home. But neither John nor Richard were willing to let go of their pride. Their weapons were re-loaded, and they returned to their firing positions. Again the scarf floated to earth, and again they fired, and again they both missed.

A few observers suggested that the 'code duello' had been satisfied, but neither man was willing to admit it just yet. For the third time the two stood facing each other, and for the third time they both fired. This time a lead ball cut through John Stanly's shirt collar. But it drew no blood, and appeals to reason and common sense fell on the deaf ears of the proud southern gentlemen. For a fourth time the pistols were loaded and primed. For a fourth time the two adversaries took their positions, and for the fourth time the cloth floated to the ground, and both men fired. This time Richard was hit in the side by a ball, and immediately dropped to the ground, blood rushing from his wound. Honor had been satisfied. The duel was over. Once again, John had won

Richard died the next day. Two months later the North Carolina legislature voted “An Act to Prevent the Vile Practice of Dueling Within This State”. The law forbid anyone who had participated in a duel from holding elective office and it was aimed specifically at punishing John Stanly. John was forced to resign from congress, but he appealed to Governor Williams, claiming it was not possible for him to have “bowed myself to the opprobrious epithets of ‘liar & scoundrel’” Governor Williams, a gentleman and a Democratic Republican, agreed, and pardoned Stanly. After that the law was largely ignored. Gentlemen simply crossed into either Virginia or South Carolina to engage in the vile practice, and over the next 58 years Tar Heel politicians fought at least another 27 duels. And because of duels, John Stanly would bury two of his own brothers, victims of their exaggerated sense of honor. Apparently the meek would inherit the earth, but not in North Carolina.

John Stanly was elected to another term in Congress, and had a distinguished career in the North Carolina house, elected Speaker three times. And he seemed to have made it his personal mission to taunt the son of his victim. When Richard Spraight Jr.was elected to the North Carolina House, an observer wrote, John “seemed to delight in torturing the son by look and gesture, and intonations of his voice, when other methods were not devised. Mr. Spaight, however, avoided an issue.” In 1820 the two ran against each other for the state senate seat, and Richard Spraight Jr. finally won - in 1835 he was even elected Governor.

Meanwhile, on Tuesday, January 16, 1827, while leading a heated debate in the North Carolina House, John Stanly had suffered a stroke. He never held public office again. He was 43 years old, a year younger than Richard Spraight senior had been when John had shot and killed him. But John Stanly lived as an invalid for another 6 long years. He rarely left his home, and fell deeply in debt. He became a bitter and angry man, abandoned by many who had once trembled at his voice and threats. But given his argumentative character, that was inevitable.

- 30 -

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)