I begin our story not where it began,

nor, unfortunately, where it ended. Instead we begin just after

eleven in the morning, Friday, June 20, 1913, with 29 year old Heinz

Schmidt bounding up a staircase, carrying a heavy briefcase in his

left hand. In his right hand he carried a gun. The first person Heinz met at the top of the stairs was

Maria Pohl She had never seen him before but he looked agitated, so

she started to ask what was wrong. Without a word, Heinz pushed a

Browning semi-automatic pistol into Maria's face. Instinctively Maria

ducked, and when the gun went off it sent a .9mm lead pellet at

1,150 feet per second a quarter of an inch past her right ear. Maria

continued her ducking movement, pushing open the door of classroom

8a. She locked the door behind her. Frustrated, Heinz pushed on the

unlocked door of classroom 8b. He burst in upon 60, five to eight

year old girls of Mrs. Pohl's class. He was the only adult in the

room. He opened fire.

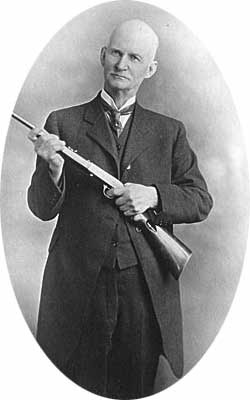

In 1884 French chemist Paul Vielle (above) mixed nitrocellulose with a little ether and some paraffin and

produced what he called pourdre blanche – white powder. When

ignited it was three times as powerful as black powder, gave off very

little smoke, left little residue behind to clog machinery, and would

not ignite unless compressed. Thousands of gunsmiths scrambled to

take advantage of Vielle's smokeless powder, in particular a

mechanical genius, the son of a gunsmith, living in Ogden, Utah: John

Moses Browning.

In Mrs. Poole's classroom, on the

mezzanine level of the St. Marien Shule (St. Mary's School) in the

Bremen, Germany, the Catholic girls were screaming, and diving under

tables. One was heard to cry out, “Please, Uncle, don't shoot us.”

But Heinz was not listening. He fired until his gun was empty, then reloaded a new clip, and continued firing. Two of the girls were shot dead on the

spot, Anna Kubica and Elsa Maria Herrmann, both seven years old.

Fifteen other girls were wounded. When his gun jammed, Heinz pulled from

his bag yet another Browning model 1900 semi-automatic pistol. In

the momentary lull, the girls rushed out of the classroom, trying to

escape down the stairs.

When John Moses Browning's own son

asked if the old man would have become a gunsmith if his father had

been a cheese maker, John pondered the question for a moment before

admitting he probably would not have. Then he burst out laughing and

assured his son, “I would not have made cheese, either.” But

John's Mormon father had been a gunsmith, and a good one. And John

was a better one, so famous he would eventually be known as “The

Father of Automatic Fire.” He would hold, in the end, 128 patents and design 80 separate

firearms. One website contends, “It can be said without

exaggeration that Browning’s guns made Winchester. And Colt. And

Remington, Savage, and the Belgium firm, Fabrique Nationale (FN). Not

to mention his own namesake company, Browning” John Browning

developed the Browning Automatic Rifle (the BAR), used in two world

wars, as well as both the thirty and “Ma-Deuce” fifty caliber

machine guns still in use by the US military, almost century later,

all of which he sold to the U.S. government for a fraction of their

royalty value. But in the beginning, his most profitable work was his

invention of semi-automatic pistols.

Heinz ran after the girls, firing from

his fresh pistol - he had eight more in the bag, and a thousand

rounds of ammunition. Eight year old Maria Anna Rychlik died at the

top of the stairs. In her panic, little seven year old, Sophie

Gornisiewicz, tried to climb over the stairwell banister. She

slipped and fell and when she landed, Sophie snapped her neck.

Following the screaming children, fleeing for their lives, Heinz ran

down the first flight of stairs to the landing.

John Browning never worked from

blueprints. In his own words, “A good idea starts a celebration in

the mind, and every nerve in the body seems to crowd up to see the

fireworks.” John would sketch rough designs of the tools he would

need to make his gun, to explain them for assistants and lathe operators. Between

1884 and 1887, he sold 20 new designs to Winchester firearms.

Explained one of the men who worked with him, “He was a hands-on

manager of the entire process of gun making, field-testing every

experimental gun as a hunter and skilled marksman and supervising the

manufacturing. He was also a shrewd negotiator. He was the complete

man: inventor, engineer and entrepreneur.”

On the landing, Heinz paused to lean

out a window and fire at boys, who were running away from the school.

He wounding five of them. A carpenter working on a nearby roof was

hit in the arm. Several apartments in the line of fire were

penetrated by shots from Heinz Browning guns. But as he paused to

reload, the gunman was now interrupted when a school custodian named

Butz landed on his back. The two struggled for a moment until Heinz

shot the janitor in the face. Grabbing his brief case still heavy

with guns and ammo, Heinz ran back up the stairs.

Browning's design philosophy on

reliability was simple. “If anything can happen in a gun it

probably will sooner or later.” In his new ingenious blow-back

pistol, the breech which received the bullet's propelling explosion

was locked in place by two screws. Instead, the “action” which

converted the recoil was a reciprocating “slide”, attached

front and rear to the gun's frame. When the gun was fired the barrel

and slide recoiled together for two-tenths of an inch, and then the

barrel disengaged from the slide. The barrel swung downward clearing

the breech, so the spent shell casing could be ejected.

As Heinz reached the top of the stairs

again, stepping over the bodies of the wounded girls, he was

confronted by a male teacher, Hubert Mollmann. They struggled for a

moment before Heinz shot him in the shoulder. Mollman fell, but the

teacher still clawed at the shooter, tackling him and bringing him

to the floor. Kicking free, Heinz sat up and shot Mollmann in the

stomach. Heinz then stood over the moaning instructor, reloaded,

picked up his brief case, and waked quickly down the stairs for a

final time. Outside, a crowd of neighbors and parents had just

reached the school.

The retreating slide compresses a

recoil spring. Once fully compressed, this forces the slide back. As

it does it strips a new round off the top of the magazine and

rejoining the barrel, slides the new round against the breech. The

gun is now ready to fire again. All that is required it to pull the

trigger again. When the Belgium firm Fabrique Nationale tested a

Browning prototype in 1896, it fired 500 consecutive rounds without

a failure or a jam, far superior performance to any other gun then on

the market. In July of 1897 FN signed a contract to manufacture the

weapon, and over the next 11 years would sell almost one million of

the small lightweight pistols to European military - and some 7,000

to civilians.

Cornered at last on the ground floor of the school, Heinz was swarmed

by men, pummeling and beating him to the ground. The briefcase was

wrenched from his grip, and the Browning pulled from his hand. The

crowd dragged him outside and there the beating continued. It seems

likely he would have been lynched, had not the police arrived to

place him under arrest. As they dragged him off to jail, Schmidt

called out, “This may be the beginning, but the end is yet to

come.”

The United States Army liked the

Browning 1900, and its improved model 1903. But they wanted more

stopping power. So John Browning went back to his work bench and within a few

months redesigned the weapon to fire a larger, forty-five caliber round. That

weapon, the Browning model 1911 pistol, would be the standard

American military pistol until it was replace by a 9mm weapon in

1985. Interestingly, when John Browning died of hear failure at his

work bench (above), on November 26, 1926, the weapon he was designing would

evolve into the gun that replaced the Browning 1911. In his obituary,

it was said of John Browning, “Even in the midst of acclaim, when

the finest model shops in the world were at his disposal, he

preferred his small shop in Ogden. Embarrassed by praise, indifferent

to fame, he ended his career as humbly as it started.”

The attack on the St. Mary's School in

Bremen lasted no more than fifteen minutes, from first shot to last.

During that time, Heinz Schmidt had fired 35 rounds. Eighteen

children had been wounded, and five adults. Three girls had died

instantly of gunshot wounds. Little Sophie with the broken neck, died

within a day. Four days after the bloodbath, the four little girls

were buried. Three thousand marched in their funeral procession (above) . Four weeks later, the fifth victim, five year old

Elfried Hoger, succumbed to her wounds an died. All that has changed since 1913 is the technology used to design and make guns. And yet we continue to pretend that nothing has changed.