I want to take you back to a time when there were just two million Hoosiers in the whole world, and yet Indiana had 13 seats in the United States House of Representatives and 15 electoral votes. Today they have just eight nine, and 11 electoral votes. Even more improbable to modern ears, this smallest state west of the Allegheny mountains was a crucial "battleground" state, oscillating like a bell clapper, clanging first Republican and then ringing Democratic, changing six times between 1876 and 1888, swinging each time at the whim of some 6,000 fickle independent voters.

Things came to a head over the winter of 1885 when the dynamic Democratic Governor Isaac Gray (above), seeking a lasting majority for his adopted party, jammed through a gerrymander redistricting of state legislative offices, by re-designing ten traditionally Republican state Assembly seats so they would elect Democrats instead. This would prove to be such an outrageous power grab, a Federal court would declare it unconstitutional in 1892 However, the savvy Gray knew that the voters would take their revenge much sooner than the courts.

So, in the summer of 1886, Grey convinced his Lieutenant Governor, Mahlon Manson. to take early retirement. Then he scheduled to fill that post in the mid-term elections, midway through his four year term. And as Gray had expected, the Republican base was so energized by the gerrymander, that their party was swept back into power that November with a 10,000 vote majority, recapturing seven of those redistricted Assembly seats. (The state Senate, serving 4 year terms each, remained 31 Democrats and 19 Republicans.)

But more importantly for Governor Gray, the newly elected Lieutenant Governor was a Republican, Robert Robertson. Thus, should Gray offer his resignation in exchange for the Republican dominated legislature appointing him an United States Senator , they were likely to agree, since that would make the Republican Robertson the new Governor. And that would move Gray to the United States Senate, one step closer to the White House. This was not an impossible dream, as another Hoosier politician would shortly prove – one, Benjamen Harrison.

Yes, Grey (above) had a nifty plan, clever enough to be worthy of Machiavelli. But it faced one insurmountable hurdle. Governor Isaac Grey was without doubt the most hated Democratic governor among Democrats, in the entire history of the state of Indiana. He was the original DINO, Democrat in Name Only.

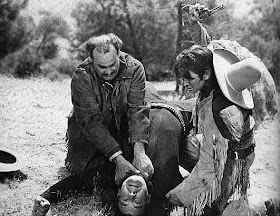

Twenty years earlier, at the close of the Civil War, this same Isaac Grey had been the Republican Speaker of the state Assembly (above). To achieve that task Gray had literally locked the doors, preventing Democrats from bolting the building and thus denying a quorum to the Republican majority. While the trapped Democrats sulked in the cloak room, Speaker Grey staged votes for the 13th, 14th and 15th reconstruction amendments to the U.S. Constitution. It had been another scheme worthy of Machiavelli. But loyalists in the Democratic party never forgot Grey had counted them as "present but not voting". And as the Assembly session for 1887 opened, these hard liners were willing to set the state on fire if they could also burn up Isaac Gray's Presidential dream boat.

The Indiana State Senate (above) was about to come into session at 9:35 on the morning of Saturday February 24th, 1887, when Lt. Governor Robertson entered the second floor chambers to take his seat as President pro tempore of the Senate. The Democrats physically blocked him from reaching the dais. He shouted from the floor, "Gentlemen of the Senate, I have been by force excluded from the position to which the people of this state elected me.” But at this point the acting-President pro tempore, Democratic Senator Alonzo Smith, ordered the doorkeeper, Frank Pritchett, to remove the Lt. Governor, “...if he don't stop speaking.”

As the doorkeeper and his assistants advanced on Roberts, he announced, “They may remove me. I am here, unarmed.” Smith testily responded, “We are all unarmed. We are fore-armed, though.” That belligerent mood was now general in the chamber. Republican Senator DeMotte from Porter county shouted something from the floor, and acting President Smith ordered him to take his seat. Responded DeMotte, “When he gets ready, he will.”

As the Lt. Governor was dragged toward the rear doors of the Senate Chamber a Republican Senator shouted that if he went, all the Republicans were going with him. President Pro tem Smith shouted back, “They can go if they want to. They will be back, ” he predicted. At this point Republican Senator Johnson challenged the chair directly, telling him, “No man will be scared by you.” “You're awfully scared now, “ said the Democrat. “Not by you”, answered the Republican. .

A general fight now broke out in the Senate chamber, with the outnumbered Republicans giving such a good account of themselves that one Democrat drew a pistol and – BANG! - shot a hole in the brand new ceiling of the still unfinished statehouse. Into the acrid gun smoke and sudden silence this unnamed Democrat announced that he was prepared to start killing Republicans if they kept fighting.

With that, Lt. Governor Robertson was thrown out of the Senate and the doors were locked and bolted behind him. As the official record notes those were “...the last words spoken by a Republican Senator in the 55th General Assembly.” The Senate then tried to get back to business, appropriately taking up Senate bill 61, setting aside $100,000 for three new hospitals for the mentally insane. It was decided it was self evident the state was going to need them, and the measure was approved by a vote officially recorded as 31 Ayes, 0 nays and 18 “present but not voting”. Ah, revenge must have seemed sweet – for about half an hour.

Outside in the central atrium, the gunshot had attracted a crowd, mostly from the Republican controlled House on the East side of the capital. Faced with a bruised and enraged Robertson, the Republicans caught his anger. Similar fights sparked to life in the chamber of the House of Representatives, and a “mob” of 600 angry Republicans descended upon every wayward Democrat in the building, punching and kicking them, and, if they resisted, beating them down to the marble floors of the brand new “people's house”.

Eventually, the pandemonium returned to its source; the Republicans laid siege to the Senate chamber. They beat against the doors, and smashed open a transom. Vengeful Republicans poured into the great room. The haughty Democrats were assaulted in their own chamber and thrown out of it. By now Governor Grey, down in his offices on the first floor, had heard the ruckus, and had called in the Indianapolis Police. Four hours after the legislative riot had begun, order was restored to the capital of Hoosier democracy. History and many newspapers would record it as the “Black Day of the Indiana Assembly.”

The following Monday the triumphant Assembly dispatched a note to the battered Senate Democrats, that they would have no further correspondence with the upper house. The Senate counter-informed the Republicans in the lower house, ditto. State government in Indiana had ground to a halt. Lt. Governor Robertson never presided over the Senate, and Governor Gray never served as a Senator. He came to be known as the “Sisyphus of the Wabash”, after the legendary Greek king, renown for his avariciousness and deceit. A few years later Hoosiers elected to choose their Senators by popular vote, I suppose under the theory that the general population of drunks and lunatics could do no worse then the professional politicians had done already.

_03.jpg)