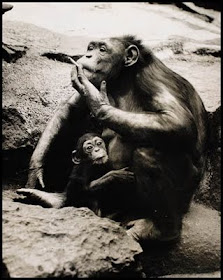

But this strategy for defense played right into the human trait of becoming addicted to things that are bad for us. By 2,000 years ago the Mayans were using tobacco to get a rush from nicotine. But their favored method of delivery – as an enema – limited the distribution of the drug, not to mention the mobilty of the users. Still, the way these two life forms meshed together, like gears in a machine - a plant which produced a poison to protect itself and a creature which tended to become addicted to poisons – may be the ultimate proof that humans bring out God's sense of humor. Which makes sense since it seems that humans seem to bring out God.

In 1492 Columbus arrived, uninvited, in the new world and the natives presented him with a canoe filled with fruit and “dried leaves”. The natives were probably hoping Christopher would set the canoe on fire while sitting in the canoe and smoking the leaves. Instead the Spaniards ate the fruit and threw the leaves away; no word on what they did with the canoe.

However a later Spanish explorer, Rodrigo de Jerez, who was in Cuba dreaming of gold and the good life, tried “drinking” the smoke from the burning leaves. He was immediately addicted. When he brought his new addiction back to Spain with him, he was arrested and thrown into a dungeon. When he was finally released 7 years later, the streets of Seville were crowded with addicts merrily puffing away in public. Ironic, huh.

By 1577 English physicians were recommending tobacco as a treatment for toothache, worms, lockjaw and oddly enough, cancer. In 1603 they petitioned the king to make tobacco a controlled substance, not because it was unhealthy but because they were not getting their cut of the profits. And in 1610 Sir Francis Bacon made a note that he really wanted to quit smoking but was finding it really hard to do. It would take another three hundred and fifty years before the American Medical Association would come to the official conclusion that nicotine is addictive.

In 1612 John Rolf harvested Virginia’s first crop of tobacco. Three years later his first shipment hit the streets of London. The result was similar to the introduction of crack in American inner cities in the 1980’s. By 1618 there were “…7,000 shops, in and about London, that doth vent tobacco”, according to Mr. Barnaby Rich, a tobacco addict.

As the weed spread around the globe, many governments set a zero tolerance level. Sultan Murad IV executed 18 smokers a day for ten years. It did not work. Czar Alexis sent first time smokers to Siberia with their noses slit. Second time smokers were executed. That did no good. In China if you were caught carrying tobacco with the intent to distribute the penalty for a first offense was decapitation. There is no record of any second time offenders, so in that regard the zero tolerance worked. And yet, the weed still thrived as a personal sin, even in China. Those who advocate the standard American approach of punishment first, toward cocaine and marijuama, might want to consider the Chinese failure with tobacco. It seemed there was only one thing that would make smokers stop smoking.

Lung cancer was first described in 1761 by, appropriately enough, Giovanni Morgagni. He was the inventor of pathology. He described it as a rare affliction. And even a century later, the disease accounted for only 1% of all cancers.

However, less than a century after that, (by 1927) as cigarette smoking became more common, lung cancer had climbed to 14% of all autopsies. Dr. Fritz Lickint made the first statistical link between smoking and lung cancer in 1928. Five years later the prestigious “Journal of the American Medical Association” began carrying advertising for cigarettes in their own publication. And, oddly enough, research into smoking and cancers, began to fade from the pages of that publication.

The addictive quality of tobacco should have been obvious from the actual advertising campaigns used to sell cigarettes. “Not a cough in a (rail) car load”, “More Doctors Smoke Camels than any other Cigarette”, “L and M cigarettes. Just what the doctor ordered”... "Making smoking 'safe' for smokers” (who else would it be safe for?), and my favorite, “We're tobacco men ... not medicine men”.

And the rationalization approach was also big along Madison Avenue, the advertising venue of choice in mid-twentieth century America. "When smokers changed to Philip Morris, every case of nose or throat irritation--due to smoking--either cleared up completely or definitely improved”, “That must be why my mother started smoking Pall Mall's when she was 15”. And then there was the confusing yet illogical approach. “39,468 dentists say, "Smoke Viceroy Cigarettes.” Who cares what dentists say about lung cancer? If those catch phrases didn’t drive people away from tobacco, nothing could.

Consider the particular brand of cigarettes called “Marlboro”. It was first introduced in 1924 and marketed as an upscale cigarette for women (“Mild as May”). It struggled as an “also-ran” until Phillip Morris reintroduced it as a filtered cigarette.

The new advertising campaign featured a craggy faced cowboy working the range, with the theme music from “The Magnificent Seven” swelling underneath. By 1957 Marlboro was the best selling cigarette in the world. The only problem was that the original “Marlboro Man”, Carl Bradley, actually smoked a different brand of cigarettes (“Kools”). Luckily for Phillip Morris, Carl was thrown off a horse into a pond and drowned before anybody found that out.

Of the approximately one dozen men who replaced Carl in print and television ads over the next forty years, three of the "Marlboro Men" died of lung cancer (Wayne McLaren, David McLean and Dick Hammer). By the 1970’s the brand was unofficially known as “Cowboy Killers”. But that didn't seem to hurt sales. I used to smoke them myself.

Today, with 1/3rd of the world’s population still smoking tobacco, chewing tobacco or inserting tobacco enemas, 4,000 Americans still die each year (5.4 million world-wide) from tobacco caused cancer, strokes, or house fires caused by smoking. The number of fires caused by tobacco enemas is thought to be insignificant, but I remain suspicious of this meathod of nicotine delivery.

Under heat Cigarettes (or little cigars) convert the nicotine fortified tobacco contained in modern cigarettes into 60 various carcinogens, and 96% of all lung cancer patients each year describe themselves as moderate to heavy smokers.

These figures mean that smoking tobacco has killed far more people than smoking marijuana. And yet, despite this, every day we send people to prison for selling the “gateway drug” while the only tobacco related criminals in jail are those caught avoiding state cigarette taxes. Yea, God must be having a real laugh over his experiment with tobacco.

- 30 -