I

know Gettysburg (above) has been portrayed as a sleepy agricultural center

before Colonel Elijah White's Virginia “Commanches” galloped into

town that rainy Friday noon – 26 June, 1863. Young student Tillie

Pierce, was abruptly sent home from the Gettysburg Girls Seminary.

“I had scarcely reached the front door” she wrote later,

“when...I saw some of the men on horseback...Clad almost in rags,

covered with dust, riding wildly, pell-mell down the hill toward our

home! Shouting, yelling...brandishing their revolvers, and firing

right and left.” But a diverse community had already been gravely

wounded before the Confederates even broached the city limits.

In

1860, the citizens of Gettysburg thought their future was bright.

After four years of effort the Gettysburg Railroad Company had

completed 17 miles of track from Hanvover Junction, through New

Oxford, to the new 2 story station (above) at the corner of Carlise and

Railroad Streets.

What had financed this investment was a 20 year

growth in the backyard construction of farm wagons and buggies,

stamped with the good local German names of their makers, like

Studebaker, Culp, Danner, Ziegler and Troxell.

Their customers were the plantation owners and farmers in Maryland, Virginia and further south. And with

the outbreak of the civil war many of those markets were cut off...

...while the lucrative contracts for the northern war effort favored

larger manufacturers (above) in cities like Philadelphia and Harrisburg. By

the third year of the war, ambitious young white men were leaving

Gettysburg to join the army or for jobs they could not find in a

small Pennsylvania town. Left behind were middle aged men, women and

blacks, because neither were considered players in the larger

community.

In

1860, being just 10 miles from the Mason-Dixon Line, there was a

strong if small African American community in Gettysburg. But we

have little contemporaneous record of what the 8 % of Gettysburg's

2,400 residents who were African American experienced during the 1863

invasion, such as diaries or letters, in part because revealing

education was dangerous for people “of color” even in a “free”

state. But there is reason to believe that two weeks earlier the 200

black adults in Gettysburg had gotten warning of the coming rebel

invasion. Caucasian school teacher “Sallie” Myers, complained she

got no sleep on the night of Monday, 15 June, because “the Darkies

made such a racket.” Those “darkies” spent that night packing

their belongings into wagons and heading north before dawn.

All

knew that if the rebels captured them, even those born free, they

would be driven south in bondage, and the women, it must be assumed,

would be raped. Still, many stayed. Eventually at least fifty

Gettysburg men, women and children - 1,000 from all of Pennsylvania -

would suffer being sold on Virginia slave

blocks or forced to slave for the rebel army. To say the American

Civil War was not about slavery is to ignore the priority given to slave

hunts by Rebel soldiers in the 1863 invasion of Pennsylvania.

So

why did some not run? For blacks, running meant freedom, but it also

meant poverty, at least for a time. The fifty blacks who were

employed in Gettysburg, such as 28 year old laundress Margaret "Meg" Palm (one

of 17 working women) or Pennsylvania College janitor John Hopkins (above),...

...or tenant farmer Basil Biggs (above, with family). had to balance their salary against

their freedom. For the dozen or so black property owners, like wagon

maker Samuel Butler, restaurateur Owen Robinson, or farmer Abraham

Brien, the choice was between freedom and loss of status.

But

for Meg Palm (above) there was also a moral obligation to stay. Beyond her

devotion to her husband Alfred and infant son, Joseph, Meg was a

station master on the Underground Railroad, smuggling escaped slaves

to freedom in Canada. Known as “Maggie Blue Coat”, for the used

military jacket she wore, she was infamous to the slaver catchers in

Maryland, who had already tried to kidnap her at lest once. But Meg

was not a small woman in size or in courage, and she had battled her

attackers bare handed. That night she saw Alfred and Joesph flee

north, to safety, while she stayed behind to continue helping the

weakest most recent survivors of the south's “pecular institution”.

Tillie

Pierce (above) continued her story, writing, “Soon the town was filled

with infantry, and then the searching and ransacking began in

earnest. They wanted horses, clothing, anything and almost everything

they could conveniently carry away...Whatever suited them they took”

Well, that was not quite the way it happened.

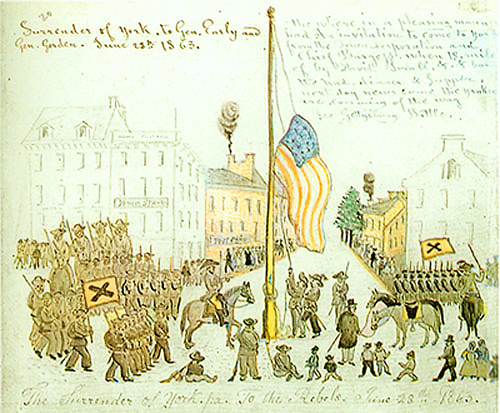

Just

after General Gordon's men occupied the city square and chopped

down the flag pole, his boss arrived from Mummasburg.

The cranky, hot tempered 46 year old

Major General Jubal Anderson Early (above) set up office near the town square, and handed the city

council a demand for 60 barrels of flour, 6,000 pounds of bacon,

1,000 pairs of shoes and 500 hats. If they did not hand over these

items, he promised to burn the town. It was not an idle threat.

One

of the rebel's primary justifications for invading Pennsylvania was

to transfer the cost of supporting the war from the exhausted farms

and towns of Northern Virginia, onto fat and prosperous Pennsylvania.

Early had brought 15 empty wagons across the Potomac, to be filled

with “confescated” food and clothing. Because so many of his men

needed shoes, the rumor persisted that Gettysburg held a shoe

factory, or a warehouse. It did not. And most private stocks of

clothing and “dry goods” in town had already been sent across the

Susquehanna River, to safety. The council explained this to General

Early, and invited him to look for himself. So he did.

What

he found was almost not worth the effort. In railroad cars left on a

siding near the train station, his men located the food meant to

support Colonel Jennings' 700 man militia regiment for three days -

2,000 Union army rations. Each individual ration was 10 ounces of

canned salted meat and a 1 pound of 3 inch by 3 inch dehydrated baked

briskets (above) - called" hardtack". The soldiers were expected to crumpled

them into their coffee for breakfast, chew them for lunch on the

march, and boil them into mash or grill them into paddies for dinner.

Distributed to Gordon's 1,500 men, this would only give them enough

energy to reach their next target – York, Pennsylvania – where

they would have to repeat the effort.

Hidden

in all of this was the truth of the rebel 1863 invasion. It was just

a raid. General Robert E. Lee, commander of the 70,000 man Army of

Northern Virginia, had no hope of holding or occupying any part of

Pennsylvania. And come morning, Jubal Early (above) and his entire corps

would be leaving Gettysburg, moving on to find enough food and

clothing to keep moving.

So

after stripping the 170 captured militia of their weapons, horses and

shoes, “Old Jube” took a moment to discourage them from causing

him any more trouble. He told the humiliated and frustrated men, “You

boys ought to be home with your mothers and not in the fields where

it is dangerous and you might get hurt.” The unionist were then

locked in the Adams county courthouse until they could individually

sign an oath pledging not to serve again until they had been

exchanged for a rebel parolee.

To

protect the looters, General Early sent White's cavalry out to

“picket” the roads into Gettysburg. And on the Baltimore Pike

these rebels surprised the men farmer-turned-Captain Robert Bell had

earlier posted and then in his haste to retreat, forgotten. The

rebels demanded the startled militia surrender. Instead the militia

spurred their horses to run. The rebels fired.and several Gettysburg

men fell from their saddles. Later, a horse with familiar tack was

being led back into town, when a Gettysburg woman asked if the

“Commanche” who held the bridle knew what had happened to the

rider. The Virginian replied, “The bastard shot at me, but he did

not hit me, and I shot him and blow ed him down like nothing, and here

I got his horse and he lays down the pike.”

Mill

owner James McAllister found the body of the horse's owner the next

day, lying in a field along the Baltimore Pike, just south of

Gettysburg. He identified the dead man as 21 year old George

Washington Sandoe (above, right). George had joined the militia just nine days

earlier, and he died within 2 miles of his own farm, south of Mt.

Joy Church..

In the morning, after the rebels had abandoned the town,

Mr. McAllister took George home to his wife of 4 months and 7 days,

Dianna Anna Caskey Sandoe (above). She was carrying George's unborn son,

Charles. Dianna never remarried. And George Sandoe would be the

only man killed on Friday, 26 June, 1863, thus becoming the first of

some 15, 500 men to die in and around Gettysburg over the next week.

-

30 -